Americans had reason to cheer the officers and crews of their navy. Although there had been a Continental Navy during the Revolutionary War, the US government had sold its last ship during the 1780s and did not create a new navy until 1794.

American sailors fought for “Free trade and sailors’ rights”—an object with which “our men could but sympathize, whatever our officers might do." American sailor Samuel Leech

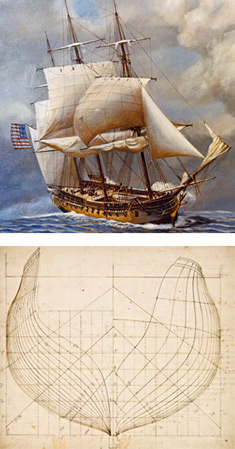

Painting by Rear Admiral John W. Schmidt, Drawing by Joshua Humphreys and Josiah Fox

Once the Algerian crisis had been settled, the construction of three super frigates was suspended, while three others slowly crept toward completion. The United States, however, was also caught in the middle of the conflict between Great Britain and France that erupted in 1793 and would continue with some interruptions until 1815. Being neutral in a world at war was not easy. In 1794 the United States faced a crisis with Great Britain that was settled by the Jay Treaty. The French viewed this agreement, in which the Americans accepted British definitions of contraband to obtain some commercial rights to trade with Great Britain, as a violation of the 1778 Franco-American alliance. Having come to the aid of the Americans during the Revolutionary War, the French were outraged by the American willingness to come to terms with the British. The French began to seize American shipping leading to the Quasi-War (1797–1800). In response the United States began a rapid naval build up, completed all six super frigates, and purchased and constructed other vessels bringing the navy to a total of 33 ships. The navy depended upon a pool of officers and sailors who gained experience in the expanding merchant marine. The Quasi-War, which included several naval victories, enhanced that experience. Jefferson wanted to shrink the navy once he became president in 1801 and rely on gunboats for coastal defense. However, a war with Tripoli meant keeping several frigates and other ships on active duty in the Mediterranean as nursery for sailors and a new crop of officers, including men like Stephen Decatur, whose seamanship, dashing, and bravery won them fame and promotion. In the process the navy established a tradition of excellence.

more ship

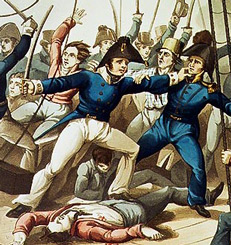

Painting by M. Dubourg, Public Domain Image

Motivation mattered. The British navy, too, had seasoned captains and crews, and they had centuries of experience in designing and building warships. But the Americans had an intangible asset. Samuel Leech, who had served on the Macedonian when it fought the United States and later served in the American navy, acknowledged that the American super frigate had an advantage in size, guns, and men. But he also believed that the seamen “in the two ships fought under the influence of different motives.” Leech briefly traced the history of impressment—the forced recruitment of sailors into the British navy. This practice, which included the taking of thousands of American citizens as well as British subjects, was one of the leading causes of the War of 1812. Many sailors on the Macedonian had been swept up by press gangs in ports and on the high seas. Such men might be less than eager to fight. Moreover, some of the sailors on the Macedonian were Americans who had been taken from American merchant vessels and who were “inwardly hoping for defeat.” In comparison, the men in the United States Navy were volunteers, who received better treatment and knew that they were fighting for “Free trade and sailors’ rights”—an object with which, as Leech explained, “our men could but sympathize, whatever our officers might do.”

Part of a series of articles titled “The Luxuriant Shoots of Our Tree of Liberty:” American Maritime Experience in the War of 1812 .

Last updated: March 6, 2015