Part of a series of articles titled African American Communities Along the C&O Canal.

Article

St. Phillips Hill (the Palisades), NW DC

The historical African American community of St. Phillips Hill formed during the Reconstruction Era in what is now the Palisades neighborhood of Washington, DC, along Chain Bridge Road north of Conduit Road. The residents coalesced around two African American institutions. The Chain Bridge Road School was a one-room schoolhouse for African American children provided by the Freedmen’s Bureau in 1865, and the Union Burial Society of Georgetown Cemetery was founded by the community in 1868 at the intersection of Conduit and Chain Bridge roads.

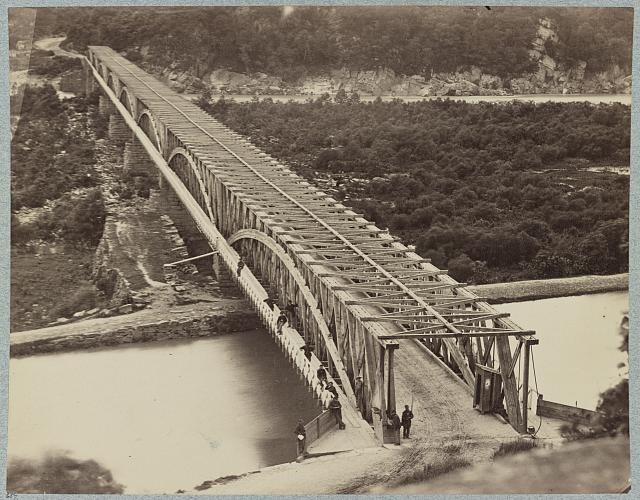

William Morris Smith, Library of Congress

In the Shadow of Battery Kemble

This area was part of the Palisades in northwest DC. During the Civil War, several forts and earthworks were constructed across the Palisades. One of these was Battery Kemble, built on high ground east of the Chain Bridge to protect the Potomac River crossing. During the war, Battery Kemble was was a place of refuge for self-emancipating African Americans, known at the time as a contraband camp. Tradition maintains that after the war’s end, the self-liberating African Americans at Battery Kemble occupied the hillside below the fortification and farmed small plots at the base of the bluff. Recent research suggests that the individual stories of the early residents of St. Phillips Hill are more nuanced and that the idea of a direct continuity between self-liberating African Americans at Battery Kemble and the settling of St. Phillips Hill is difficult to prove.During the occupation of the Palisades by the United States Army, soldiers took whatever they needed from property owners and cut down trees for firewood and building material. Captain William A.T. Maddox, a white man on whose property Battery Kemble was erected, claimed that federal soldiers felled timber worth $70,000 on his land. He received less than $7,000 in recompense in 1873. The war bankrupted Maddox, and he was forced to sell off his land to repay debts. This gave freedpeople an opportunity to acquire small parcels, ranging in size from two to five acres, for $80 per acre in the mid-1870s.

Palisades Area: Then and Now

Left image

An 1887 map of St. Phillips Hill community (which are the parcels of land in the top left), W.A.T. Maddox's land, and surrounding Palisades area of Washington D.C.

Credit: Library of Congress

Right image

Modern-day map of the Palisades area of Washington D.C. The land historically belonging to W.A.T. Maddox, which bordered the St. Phillips Hill community, is now a part of Rock Creek Park and is known as Battery Kemble Park

Credit: NPS

G.M. Hopkins and Walter S. Mac Cormac. Library of Congress

The Blackwell Family

The story of Thomas Blackwell, depicted on two of the Hopkins maps, also provides nuance to the idea that St. Phillips Hill was settled by freedom seekers who had found refuge at Battery Kemble. Thomas Blackwell was listed in the 1870 US census of Washington’s Ward 6, which lay east of the Capitol and near the Anacostia River. He was living with his wife, Harriet; his two sons, Americus C. and Louis; and his two toddler daughters, Martha and Victoria. Thomas Blackwell, his wife, and his two sons all had been born in Virginia, but the young girls had been born in DC. Given the five years’ difference between Louis’ and Martha’s ages in 1870, the family must have settled in DC between 1861 and 1866. So it is probable that the Blackwells were self-liberators who came to DC during or immediately after the war. By 1880, Thomas's son Americus Blackwell was living in the First District as a neighbor to Jacob Hayes and William Peters. Presumably, because the Blackwells had been living in northeast DC in 1870, they were not freedom-seeking African Americans who had settled in Battery Kemble’s refuge for self-emancipators during the war and continued to remain there after the war’s end. In the mid-1870s, when William Maddox was selling off his land, the second generation of Blackwells took advantage of the opportunity to establish a farmstead in the countryside. While many African Americans were made refugees by the war, and many moved from South to North, these patterns do not describe the lives of all African American families.The Next Generation Moves On

At its height in the 1910s, the St. Phillips Hill community covered the hillside below Loughboro Road and included nearly 100 families. The men of St. Phillips Hill typically worked as general laborers and farmhands while the women took in laundry and worked in domestic service positions. African Americans in St. Phillips Hill thrived and land ownership remained stable through the 1920s, with many Black-owned properties passing to the next generation. However, development pressures in the 1930s resulted in the original landowners or their heirs selling their properties and moving away. By 1938, only eight African American families remained in St. Phillips Hill. Most of the modest, frame dwellings that had characterized the Black community were razed for contemporary, single-family residences by 1940 and the Freemen's Bureau-constructed school was closed in 1941.A Second Wave of Black Migration Returns

Census and real estate data show that over one-third of the residents of St. Phillips Hill in 1940 were non-white. By 1950, fewer than 2 percent of households were non-white. This displacement was due in part to deed restrictions and racial covenants that prohibited Black home ownership in serval areas of the Palisades adjacent to St. Phillips Hill. But in contrast to this trend are several Mid-Century Modernist houses built after World War II in St. Phillips Hill. Because these parcels had been held by individual landowners and not sold to residential developers (who were responsible for entailing deeds with restrictive covenants), and because the area had been racially integrated since the Civil War, it proved to be a haven for a new, professional class of Black Washingtonians during a period of increased housing discrimination practices across the District of Columbia. An example is the Nixon-Mounsey House at 2915 University Terrace, NW. The lot had belonged to Daniel Honesty, one of St. Phillips Hill’s earliest residents, who sold it in 1937. The Art Deco-style house built on the lot was designed by two African American men: William D. Nixon, a self-taught architect and a teacher at DC’s Dunbar High School, and Howard Dilworth Woodson, a civil engineer. Completed in 1950, the residence served as Nixon’s studio and his family’s home through 1976. The Nixon-Mounsey house represents a second wave of Black migration to St. Phillips Hill.Information in this article comes from the National Park Service Historic Resource Study: African American Communities Along the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal, by Heather McMahon. Produced by the National Park Service and WSP USA Inc., 2022.

Sources

-

George William Baist, William Edward Baist, and Harry Valentine Baist, Baist’s Real Estate Atlas of Surveys of Washington, District of Columbia, Vol. III, Plate 30. Philadelphia: G.W. Baist, 1907; 1909-1911; 1913-1915; 1919-1921. Map. Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3851bm.gct00135c/?sp=33&st=image&r=0.118,0.263,1.02,0.407,0.

-

Norma Braude, Mary Garrard, Peter Sefton, and John DeFerrari, “The Nixon-Mounsey House,” Washington, DC, National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (Washington, DC: US Department of Interior, National Park Service, 2021, accessed 28 March 2022: https://planning.dc.gov/publication/2915-university-terrace-nw-nixon-mounsey-house-case-21-20).

-

Stuart Fiedel, John Bedell, Charles LeeDecker, Jason Shellenhamer, and Eric Griffitts, “Bold, Rocky, and Picturesque”: Archeological Overview and Assessment and Archeological Identification and Evaluation Study of Rock Creek Park, District of Columbia (Washington, DC: prepared for the National Park Service-National Capital Region, Washington, DC, by The Louis Berger Group, Inc., 2008).

-

“Historic African American Communities in the Washington Metropolitan Area,” Prologue DC [website] (accessed 15 October 2021, https://www.arcgis.com/apps/MapJournal/index.html?appid=5d16635c4fde41eca91c3e2a82c871e8).

-

Griffith Morgan Hopkins, Jr. Atlas of fifteen miles around Washington, including the county of Montgomery, Maryland. Philadelphia: G.M. Hopkins, 1879. Map. Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/87675339/.

-

Griffith Morgan Hopkins, Jr. The vicinity of Washington, D.C. Philadelphia: Griffith M. Hopkins, C.E, 1894. Map. Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/88693364/

-

Griffith Morgan Hopkins, Jr. and Walter S. Mac Cormac, Map of the District of Columbia from official records and actual surveys. Philadelphia: G.M. Hopkins, C.E, 1887. Map. Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/87694341/.

-

Map of the city of Washington District of Columbia (Washington?: map, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2011593651/, 1870).

-

“Mapping Segregation in Washington DC,” Prologue DC [website] (accessed 15 February 2022, https://www.mappingsegregationdc.org/#maps).

-

Kathryn Schneider Smith, ed., Washington at Home: An Illustrated History of Neighborhoods in the Nation’s Capital, Second Edition (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010).

-

Laura Treischmann (EHT Traceries), “Chain Bridge Road School,” Washington, DC. National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (Washington, DC: US Department of Interior, National Park Service, 2002).

Tags

- chesapeake & ohio canal national historical park

- civil war defenses of washington

- rock creek park

- national capital region

- national capital area

- ncr

- washington d.c.

- district of columbia

- st. phillips hill

- palisades

- choh

- c&o canal

- rocr

- rock creek park

- battery kemble

- history

- african american history

- black history

- civil rights

- reconstruction

- reconstruction era

- nixon-mounsey house

- chain bridge

Last updated: December 15, 2023