Last updated: December 28, 2017

Article

The Spruce Production Division

NPS Photo

When the United States entered World War I, German aviation dominated the skies. The Allies were desperately in need of a steady supply of airplanes, and the Pacific Northwest had just the thing to help: Sitka spruce.

In 1917, the Northwest was the national center of the lumber industry, and its forests were rich with aviation-grade spruce. But that year, tensions over unsafe working conditions and work hours led the radical labor group Industrial Workers of the World to organize strikes that stopped logging operations. To make sure that Allied airplane factories would have a steady stream of lumber, the U.S. Army Signal Corps Aviation Sector took control of the logging industry in the Northwest and created the Spruce Production Division to manage it.

U.S. Army soldiers and civilians ran the Spruce Production Division as part of a massive, nationalized home front effort to win the war. The Spruce Production Division was headquartered at Vancouver Barracks, in Vancouver, Washington, and by Armistice Day, had nearly 30,000 soldiers assigned to the division. These soldiers served their country far from the battlefields of Europe, and their work changed the course of the air war.

In 1917, the Northwest was the national center of the lumber industry, and its forests were rich with aviation-grade spruce. But that year, tensions over unsafe working conditions and work hours led the radical labor group Industrial Workers of the World to organize strikes that stopped logging operations. To make sure that Allied airplane factories would have a steady stream of lumber, the U.S. Army Signal Corps Aviation Sector took control of the logging industry in the Northwest and created the Spruce Production Division to manage it.

U.S. Army soldiers and civilians ran the Spruce Production Division as part of a massive, nationalized home front effort to win the war. The Spruce Production Division was headquartered at Vancouver Barracks, in Vancouver, Washington, and by Armistice Day, had nearly 30,000 soldiers assigned to the division. These soldiers served their country far from the battlefields of Europe, and their work changed the course of the air war.

NPS Photo

NPS Photo

Soldiers in the Woods

The Spruce Production Division sent Army troops to work side by side with civilian loggers in the forests of Oregon and Washington. Logging was a difficult and dangerous job. Many of the soldiers sent to camps had experience in the lumber industry, and were chosen for this duty because of their skill. Logging camps also retained civilian employees in certain, specialized jobs.

Colonel Brice Disque, commanding officer of the Spruce Production Division, was dismayed by the existing living conditions in Northwest logging camps. The Army installed recreation rooms, shower houses, and new sleeping quarters to help make the camps more livable for soldiers.

To counteract the damaging effects of the 1917 International Workers of the World strikes, Disque established a new union run by the Army to serve SPD soldiers. This union was called the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen, or the 4L. Membership in the 4L was required of all SPD soldiers and civilian workers at the logging camps. The 4L secured an eight hour work day, ensured that soldiers would be paid the same as civilian loggers (a higher rate than the average soldier), and required logging camps to follow military sanitary regulations. In the end, the nationalization of the lumber industry brought about many of the changes the International Workers of the World had called for before the war.

NPS Photo

NPS Photo

Soldiers in the Spruce Mill

Perhaps one of the largest achievements of the Spruce Production Division was the construction of three large lumber mills to increase production rates of milled lumber. The largest of these was constructed at Vancouver Barracks in Vancouver, Washington. Construction of this 30 acre complex began in November 1917, and the mill was operational just 45 days later.

Trucks and railroads brought spruce lumber from logging camps to the Vancouver Barracks Spruce Mill. The Army contracted with the Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway to build, maintain, and operate a three-tiered rail yard at the mill. There, logs were cut, dried, inspected, and exported to airplane factories in the Eastern United States. A big challenge faced by soldiers who worked at the mill was milling spruce logs along a straight grain. Spruce cut along a spiral or cross grain could not be used. This was especially important when cutting long wing beams.

The mill operated 24 hours a day, and employed around 5,000 men, who lived in wooden cantonments or canvas tents near the mill. The mill ran three shifts each day, and so did its kitchens, bakeries, mess halls, recreation rooms, and other facilities.

Soldiers stationed at the mill were assigned to construction or mill work. Unlike the soldiers stationed in logging camps, they were able to work primarily indoors and had access to the more cosmopolitan town of Vancouver. But soldiers at the Spruce Mill had to follow military rules more closely than soldiers in the forest camps.

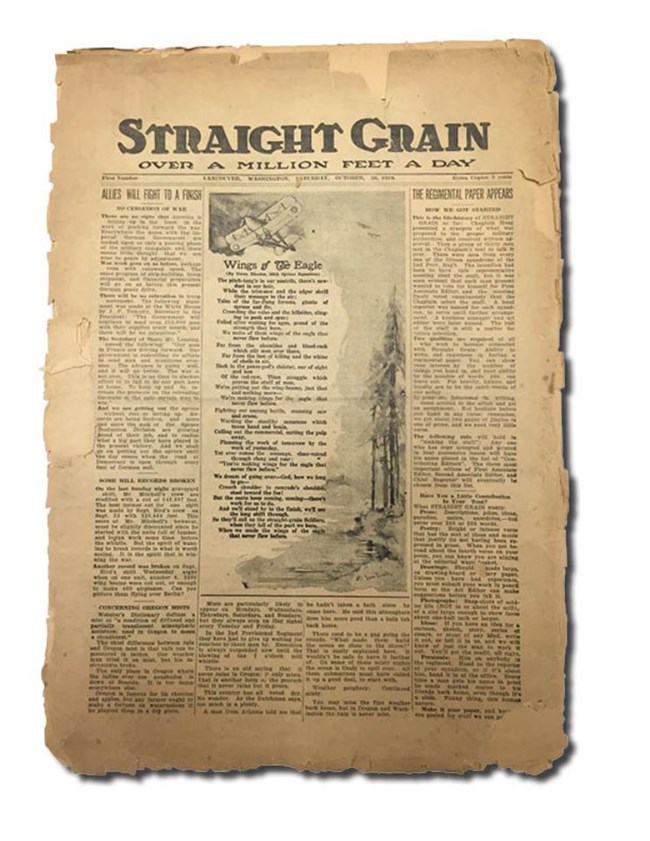

Several local and regional newspapers and magazines were published for the SPD workers and soldiers. The Vancouver Barracks newspaper was called the "Straight Grain." These newspapers kept the workers up to date on news of logging activities, conditions and the status of the war, and included articles and illustrations providing encouragement and calls for patriotism.

The archaeological remains of the Vancouver Spruce Mill complex are contained within Fort Vancouver National Historic Site. This World War I-era use of the landscape has been the focus of several field and research projects intended to enhance our knowledge and understanding of this very dynamic period.

National Archives and Records Administration

Mastery of the Air

World War I was a time of rapid change in aviation technology. Combat planes, pursuit planes, and bombers became necessary to keep control of the fighting on the ground.

In the spring of 1917, as the United States was joining the war, the Allies suffered many casualties of pilots and airplanes. The British and French militaries realized that it was not enough to try to compete with German technology - they needed to be able to manufacture enough airplanes and train enough pilots to overwhelm the Germans. The Allies ordered 100 million board feet of lumber from the United States, and by the end of the war, the Spruce Production Division had produced nearly 185 million board feet.

The spruce logged and cut by the soldiers of the Spruce Production Division allowed the allies to build more airplanes and to respond to whatever new aviation technology the Germans might develop. From 1917 to 1918, lumber from the Northwest was used to build 16,952 U.S. Army training planes, 4,881 French planes, 258 British planes, and 59 Italian planes.

Many Spruce Production Division soldiers longed to fight on the battlefield. However, their work on the home front was essential to making sure the Allies had the supplies they needed to win the war.

NPS Photo