Article

Seneca Village, New York City

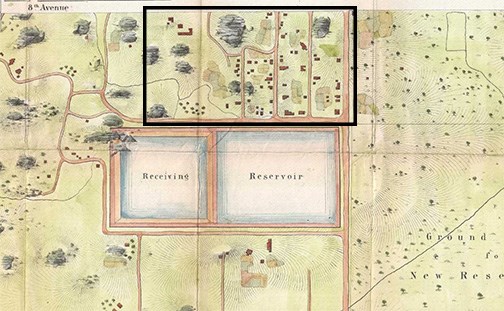

Detail from “Map of the Lands Included in The Central Park, from a Topographical Survey, June 17th, 1856” by Egbert Viele.

Frederick Law Olmstead and Calvert Vaux developed the winning plan for Central Park's design. Olmstead described it as “the first real Park made in this country -- a democratic development of the highest significance.” In 1853, the New York State legislature chose 750 acres of land in New York City to be the site of the new park. Located north of the developed downtown, the property ran from 59th to 106th Streets.

While largely rural, the land that the legislators chose was not empty. On it were several communities of people who had purchased the land in the very early years of the 1800s. One of these was Seneca Village. Free Blacks founded the village in 1825: the first free Black community in New York City. When slavery ended in New York State in 1827, the population grew as people built and rented homes here. The town grew to be a middle-class Black community of almost 5 acres. It had streets, three churches, two schools, and two cemeteries. More than 350 people lived in Seneca Village. As well as the Black population, German and Irish immigrants also lived in the community.

As the development of Central Park grew closer, newspapers and politicians began to describe the villages as “shantytowns.” They called the residents “denizens,” “squatters,” “vagabonds,” and “scoundrels.” Residents of Seneca Village fought to keep their homes and community intact. But in 1857, the city used eminent domain to forcibly remove them. Police removed those who resisted: “...the supremacy of the law was upheld by the policeman’s bludgeons.”[1] Once the people were gone, the city demolished the village. Historians know very little about what happened to the former residents.

In 2001, over 140 years after Seneca Village was destroyed, an historical marker was placed at its former location. Professors Diana diZerega Wall (City College of New York), Nan Rothschild (Columbia University), and Cynthia Copeland (New York University) directed archeological excavations at the site. These took place in 2004, 2005, and 2011. They recovered artifacts documenting the history of Seneca Village. These included beef bones, dishes, buttons, bottles, smoking pipes, a toothbrush, and the sole from a child’s shoe. [2, 3]

Central Park was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966. It was designated a National Historic Landmark on May 23, 1963.

REFERENCES

[1] Mapping the African American Past. “Seneca Village.”

[2] Foderaro, Lisa W. 2011. “Unearthing Traces of African-American Village Displaced by Central Park.” New York Times, July 27, 2011.

[3] Seneca Village Project. 2011. “Summer 2011 Excavation.”