Last updated: September 3, 2025

Article

Rare Finds in Quiet Waters: Searching Shenandoah's Springs for Hidden Life

By Christina Martin, I&M Research Scientist and Communication Specialist

July 2025

If you’ve ever come across a quiet trickle or shallow pool beside a trail in Shenandoah National Park (NP), you may not have thought about what was living there. But beneath the surface of the park’s cool, high-elevation springs, something extraordinary is going on.

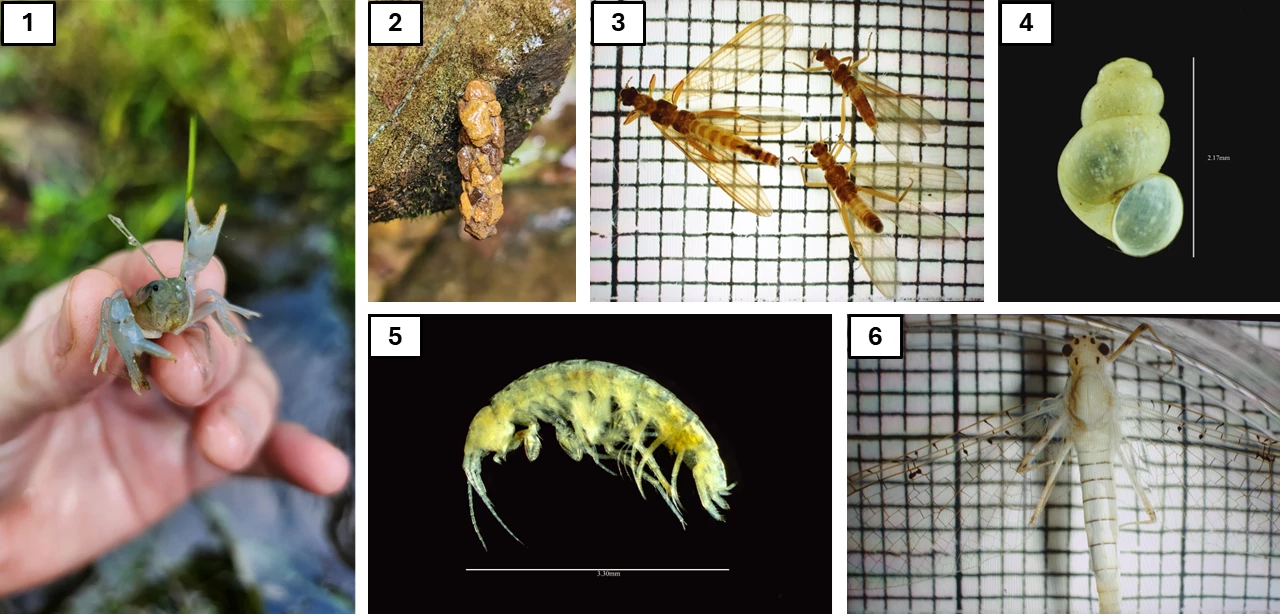

These springs, numbering in the hundreds, dot the park's landscape. More than peaceful water sources, they are biodiversity hotspots. Their consistent temperature and flow make them ideal habitats for tiny aquatic invertebrates like insect larvae, snails, and amphipods (kinds of crustaceans). These creatures may be small, but they play big roles—breaking down leaves, filtering water, and feeding animals such as birds, fish, and salamanders.

1. Crayfish held by a researcher, 2. Caddisfly case (Neophylax sp.), 3. Stoneflies, 4. Blue Ridge Springsnail (Fontigens orolibas), 5. Blue Ridge Amphipod (Stygobromus spinosus), 6. Mayfly (Ameletus sp.).

NPS/Sydney Haney (1, 2, 4, 5) and NPS/Megan Underwood (3, 6)

NPS/Elizabeth Sicking

Hidden Impacts in Fragile Places

Spring ecosystems support a remarkable range of life. Sadly, many of their inhabitants are in decline. Freshwater invertebrates, which are animals without backbones like aquatic insects and snails, are disappearing at a rapid pace. Their decline disrupts food webs and leads to a loss in overall biodiversity.

Their ecological value and sensitivity to disturbance make springs especially important to monitor—but they’re often overlooked in conservation. As climatic conditions shift and visitor use increases, scientists and park managers wondered: what’s happening to the species that live in these waters, and are visitors and park infrastructure impacting them?

Getting to the Bottom of It

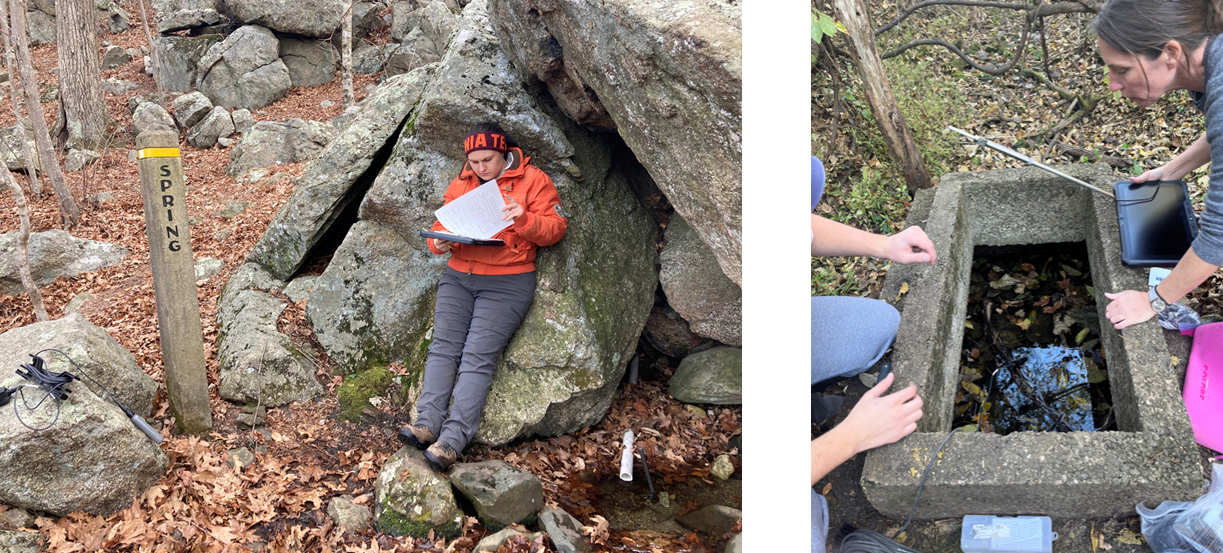

To find out, Shenandoah NP partnered with Virginia Tech and the National Park Service Inventory and Monitoring Program to study 59 high-elevation springs across the park. Researchers selected a diverse range of springs for comparison—some untouched, others equipped with boxes or pipes for water supply; some near trails, others tucked far from visitor access.

Researchers collected data at sites with different types of infrastructure, like spring pipes (left) and spring boxes (right), to understand how these modifications might affect spring-dwelling species.

NPS/Hannah Swarm

At each site, the scientists gathered three types of aquatic invertebrate samples: from the stream bottom, from the water, and from just above the water’s surface, where aquatic insects emerge as adults. All collected critters were identified in the lab by experts. Researchers also measured environmental factors like temperature, flow, and nearby trail use.

NPS/Hannah Swarm (left), NPS/Sally Entrekin (right)

They found an impressive variety of invertebrates, totaling over 200 species. Among them were 17 considered rare. These included sensitive insects like caddisflies, stoneflies, and mayflies, along with a spring-dwelling amphipod and an aquatic snail.

Always look down at the ground and check for these springs. They’re magical! These small aquatic habitats are rich in biodiversity and beauty.

What the Results Revealed

NPS

Researchers were slightly surprised to find that there wasn’t a big difference in the number or kinds of species living in modified versus unmodified springs. Much of the infrastructure had been in place for decades, so it’s possible the ecosystems have gradually adapted to changes in water flow and temperature.

The study also revealed a clear trend: rare species were more likely to be found in springs farther from trails and shelters. This suggests that foot traffic, water collection, and other disturbances could be affecting the sensitive species that call these springs home.

A Better Way Forward

This research offers encouraging news. Spring boxes aren’t causing major harm to biodiversity, so the park doesn’t need to urgently remove them. Still, Shenandoah NP managers plan to remove some boxes over time to meet long-term goals of keeping backcountry areas natural and free of infrastructure.

With the information gathered from this study, park managers can make thoughtful decisions—prioritizing infrastructure removal at springs with fewer at-risk animals, focusing conservation efforts where rare species thrive, and better accounting for spring habitats when planning new trails or facilities. In cases where sensitive species persist near heavily visited areas, additional protections will be considered.

This study is a first step toward managing these habitats in the best way. We now have a better sense of what we stand to lose, and we can pay more attention to these sensitive places and the species that depend on them.

This work shines a light on the unseen life in Shenandoah’s springs. It gives the park a stronger foundation for future stewardship and reminds all of us to tread lightly near these waters, where some of the park’s rarest animals live. With continued research and mindful management, Shenandoah’s springs can hopefully keep flowing and supporting life for years to come.

Tags

- shenandoah national park

- inventory

- inventories

- species inventory

- inventory and assessment

- inventory and monitoring division

- natural resource stewardship and science

- virginia

- biodiversity

- resource management

- natural resource management

- collaborative conservation

- mid-atlantic network

- midn

- springs

- aquatic invertebrates