Last updated: August 25, 2025

Article

Seals and Subsistence: More Than What Words Can Describe

What is Subsistence?

Photo courtesy of Chugach Regional Resources Commission with permission from Qutekcak Native Tribe

Subsistence is a term that mainly describes an Alaska-specific way of life. It revolves around the practice of harvesting, gathering, preparing, and sharing wild foods for personal sustenance. Subsistence brings food security to communities and families, but it is much more than that. Alaska Natives have been practicing “subsistence” long before the word was introduced. As St. Lawrence Island Yup’ik writer and activist Jonella Larson White explains:

While Kenai Fjords does not permit subsistence harvesting within the boundaries of the park, the landscape and resources of the park significantly impact the health and character of the regional ecosystem that has sustained Alaska Native people in the area for thousands of years.

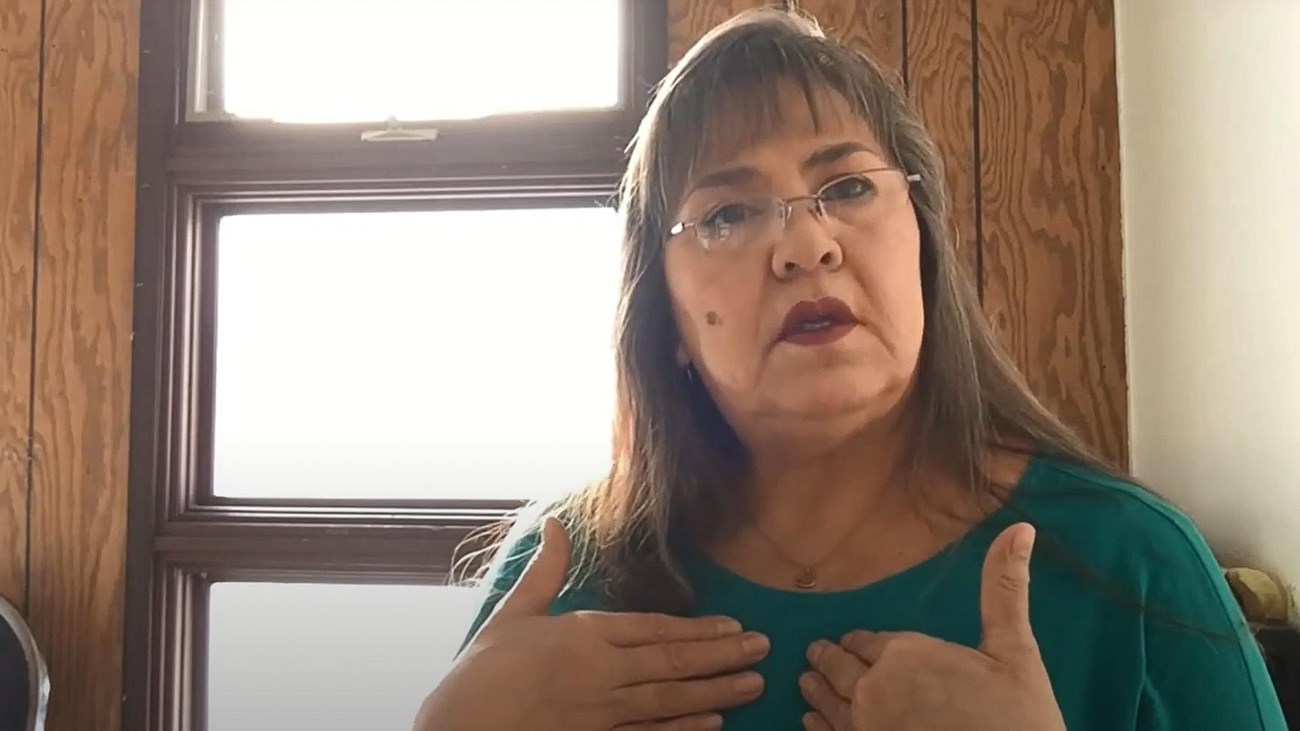

Way of Life and Well-Being

Photo courtesy of respected Elder Nancy Yeaton from the Village of Nanwalek

Unguacimtun, Ggwi nuryuglaqa qutem seni. Katurqiluanga piliarkamnek tamaa akguam piturkamek. Neqnek nuryukuma, nalluntua naten aquaciqsia. Qutem minarlaraakut. // All my life, I depended on that shoreline. I would go down to the beach to collect anything to make chowder for that night's dinner. If we needed food I knew where to get it. The beach provided for us.

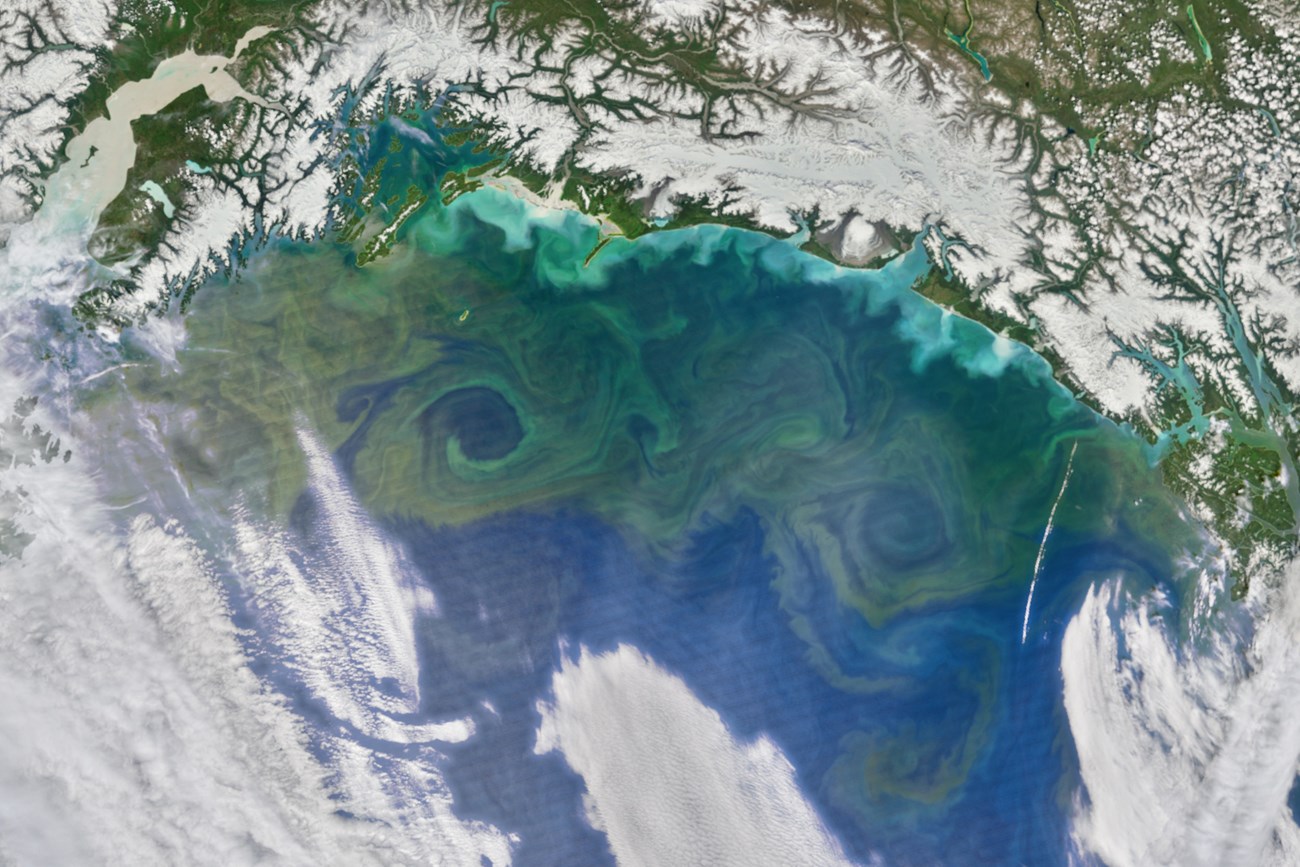

From Glacier to Table

NASA Image by Norman Kuring

Qaigyaq: The Seal

NPS Photo

Traditional Nourishment and Lifeways

Photo by Bjorn Olson, courtesy of Chugach Regional Resources Commission

Photo courtesy of Chugach Regional Resources Commission

Anchorage Museum

Joe Tanape's Seal Dance

Chugachmiut Heritage Preservation

Nancy Yeaton from Nanwalek describes Joe Tanape performing the traditional seal dance.

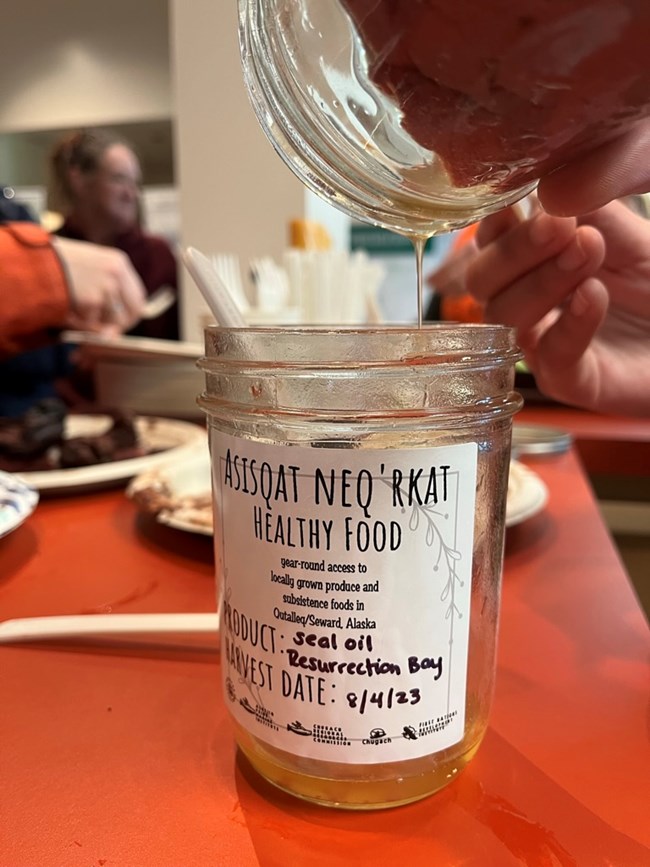

The Significance of Sharing

Photo courtesy of Chugach Regional Resources Commission with permission from Qutekcak Native Tribe

Harvesting, processing, and sharing a seal can bring a community closer together. According to one community member from Chenega Bay, “If a guy, or hunter takes a seal, he’d bring all the meat, pass the word out to the village that there’s a seal, just go down to the boat. They don’t waste it. They share it” (Haynes et al.) Another Tribal member from Port Graham shared that when he hunts, sharing is the “most important aspect of this activity (of taking seals)”. He often delivers parts of the seal to community members as directed by his mother or by his own discretion. In Nanwalek, “most distribution is along kinship lines…Whatever is left over goes to anyone else…” For that hunter, subsistence harvesting is what ties him to his community and culture. He does not speak Alutiiq, and according to him, “he currently only has subsistence.”

Photo courtesy of Chugach Regional Resources Commission with permission from Qutekcak Native Tribe

Every element of our local and global ecosystem is interlinked. As humans, we are not apart from this web of interdependence; rather, we play active roles in ecological and environmental processes. All human communities depend on the health of our surroundings for physical, spiritual, and cultural well-being, whether we acknowledge it or not. For the Sugpiaq people, the deep connection between humans and the earth has been recognized, studied, respected, and celebrated for countless generations in this area. The relationship between seals and Sugpiaq people has been nurtured over many generations, with both supporting one another. This profound connection highlights the role that all living beings play in maintaining the health of our shared planet for future generations.

Written by Ruby DiCarlo, National Park Service, in collaboration with Robin McKnight and Chugach Regional Resources Commission.

Read On

Learn how climate change and ocean issues are impacting seal populations, and in turn regional subsistence activity.