Last updated: January 21, 2026

Article

Rush Historic District Cultural Landscape

NPS

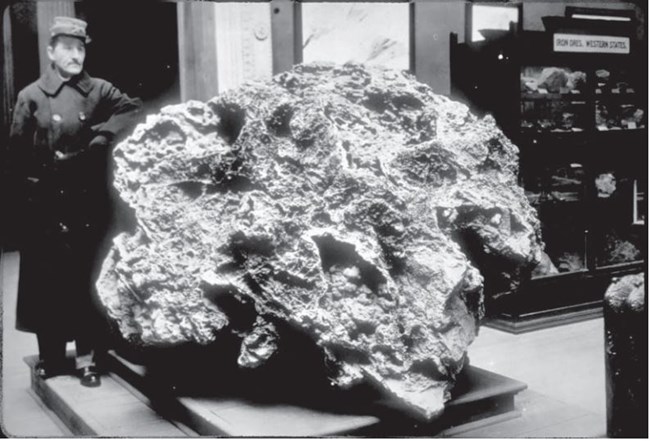

The original discovery of zinc on Rush Mountain occurred in 1880. Morning Star Mine, which would become the largest mining operation in the district, was founded in 1885. Ten different mining companies operated fourteen mines in the area. An excess supply of zinc in the postwar period resulted in a dramatic drop in prices that forced many of the mines to close.

Photo courtesy of Field Museum of Natural History, in NPS Rush Historic District Cultural Landscape Report (2017)

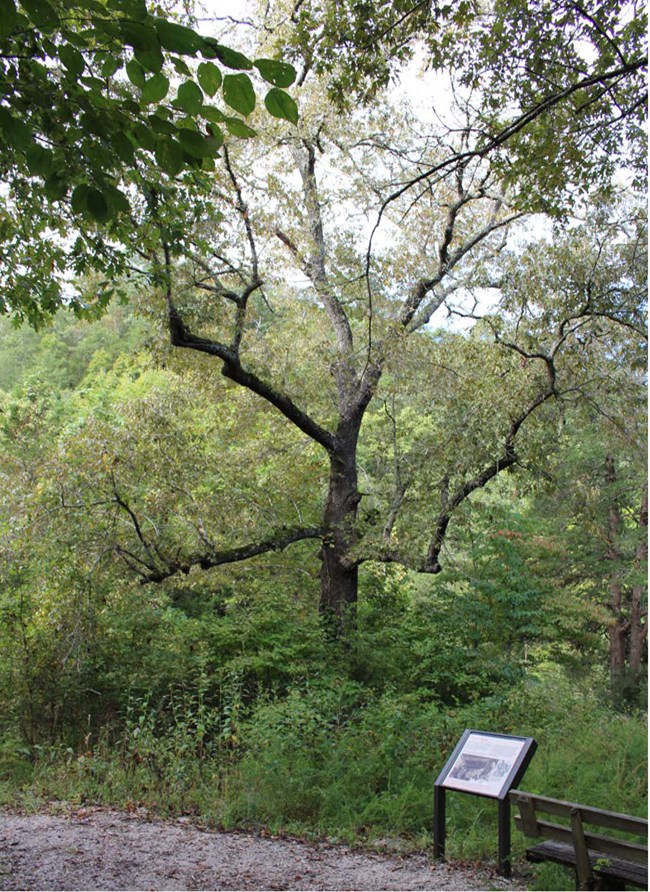

Although deterioration of the structures and the overgrowth of vegetation somewhat diminish the integrity, the district remains able to convey its historical significance. Rush Historic District demonstrates historical significance for its association with the evolution of the zinc mining industry, its vernacular architecture, and the potential to yield future archeological information related to mining.

Landscape Description

Buffalo National River encompasses Rush Historic District in Boone County, which includes 1,316 acres located in the park’s eastern half. The valleys of the Buffalo River and its tributaries, Rush and Clabber Creek, define the topographical patterns at Rush Historic District. Steep hillsides and rock outcroppings are prevalent throughout the site, along with oak and hickory forests. The seclusion of Rush Historic District and absence of modern development contribute to both the feeling and setting for the abandoned mining community.

NPS

The majority of the residences in House Row were constructed around 1899 and are wooden, simple, and one-story. Metal roof sheathing, open front porches, and pier foundations consistently appear in their designs. The extant houses face decay and exist among ruins and archeological sites. The ruins include that of the Morning Star Hotel and Mill and the site of the Hicks Hotel and Hicks General Store.

Historic Use

Human presence at Buffalo River Valley extends as far back as the Dalton period from 10500 to 9500 BCE. During this time, early people established temporary settlements along Rush Creek. Around 800 CE, Native American tribes started permanent settlements and grew squash and maize along the river. Several Native American tribes, including the Shawnee, Delaware, and Cherokee, occupied the area into the early 1800s. The Cherokee established farms along the Buffalo River and continued to embark on seasonal hunting trips upland. This use continued until the Treaty of Washington in 1828 when the federal government pressured the Western Cherokee living in Arkansas to cede their land.French prospectors from Louisiana explored the area in the early 1800s. Euro-American settlers arrived slowly during this period due to limited infrastructure in the area. The discovery of zinc on Rush Mountain and subsequent opening of Morning Star Mine in 1885 motivated the creation of new mines, a smelter, and new industries. Rush Smelter was built in 1886 to separate silver from zinc ore, however, a lack of silver quickly made its operation redundant.

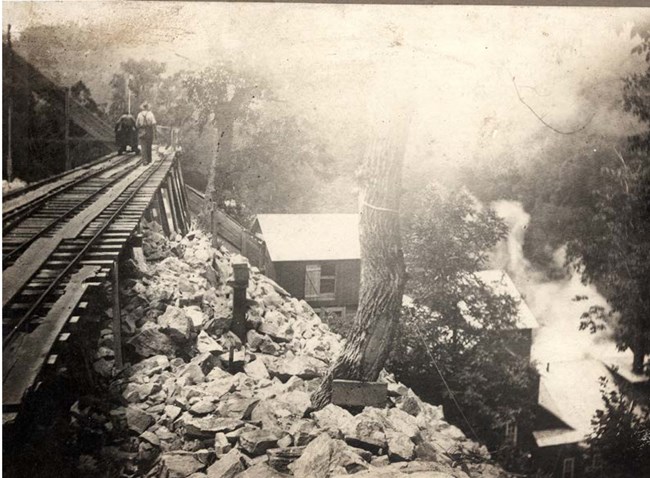

NPS / Buffalo National River Archives

Morning Star Mining Community, c. 1916

Left image

Morning Star Hotel, Mill, and Mine Community, c. 1916.

Right image

Mines were set high on hillsides. Mills were located directly below. Mining communities with support structures such as hotels, stores, and residential buildings were clustered on the valley floor.

Credit: (NPS / Buffalo National River Archives, annotation in 2017 CLR)

NPS / Buffalo National River Archives

NPS

In 1972, Congress established Buffalo National River, which included what is now known as the Rush Historic District. The National Park Service completed Rush Road improvements, stabilized structures, and built fences at the mines and tunnels in the 1980s. In 1987, Rush Historic District was listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Flooding and arson have destroyed or harmed several of the structures over the years. However, the remaining structures adequately convey the site’s identity as an abandoned mining community. The public can visit the cultural landscape to learn about historic zinc mining and mining community life. Steep gradients and a lack of walkways may make some areas of the landscape challenging to traverse.

Quick Facts

- Cultural Landscape Type: Historic Vernacular Landscape

- National Register Signifiance Level: Local

- National Register Significance Criteria: A, C, D

- Period of Significance: 1885-1931

Landscape Links

- Cultural Landscape Inventory park report: Rush Historic District

- Cultural Landscape Report and Environmental Assessment: Rush Historic Mining District (2019)

- National Register of Historic Places: Rush Historic District

- Library of Congress: Hicks Hotel and Store, Historic American Landscapes Survey

- More about NPS Cultural Landscapes