Last updated: November 2, 2022

Article

Of Adobe, Lime, and Cement: The Preservation History of the San José de Tumacácori Mission Church (Part III – Garden and Orchard)

Introduction

This is the third is a series of reports about Tumacácori National Historic Park that was featured in the Archeology E-gram Projects in Parks, September-November 2008. The previous two articles focused on the preservation history of the mission. Preservation histories are important because they summarize and interpret past preservation efforts. Archeology plays a key role in preserving historical structures, as information gained through excavation can add another dimension to comprehension of construction techniques. Archeological investigations can also reveal earlier phases of construction and contextualize structural elements. The first report in this series focused on preservation of various materials, or fabrics, that were used to build the mission. The second report recounted actions to preserve specific structures within the monument. The final report in this series addresses the cultural landscape of Tumacácori Mission NHP.

The idealized image of 18th and 19th century Spanish mission orchards and gardens in the New World is often nostalgic and romantic. Yet, the physical aspects of Mission Period orchards and gardens are poorly understood. In the mid to late 19th century, miners and ranchers traveling through southern Arizona and northern Sonora described the abandoned orchards, gardens, and acequia at San José de Tumacácori. These accounts offer tantalizing clues about the walls, fruit trees, and canal systems of the mission orchard and garden. Until recently, however, archeological excavations at the mission focused mainly on the church and convento, and little archeological or ethnographic research was done to substantiate these early accounts.

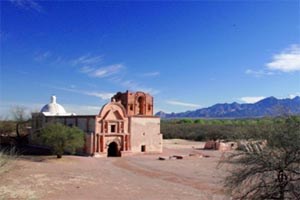

Tumacácori NHP is comprised of three Spanish mission sites: Tumacácori; Calabasas, located 9 miles south of Tumacácori; and Guevavi, located 3 miles south of Calabasas near Nogales, Arizona. At Tumacácori, the mission church’s picturesque white dome and unfinished brick bell tower dominate the local landscape. At each site the NPS protects, preserves, and interprets Spanish Colonial mission churches and associated ruins.

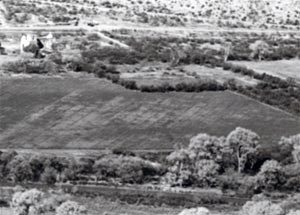

In 2002, the boundary of Tumacácori NHP was expanded to include the mission orchard/garden and agricultural fields, offering an opportunity to study Mission Period garden construction and design. Archeological investigations in the mission orchard/garden began in 2004, and ethno-historical and ethno-botanical research on Spanish mission gardens and orchards are currently underway. The goals of these studies are to increase understanding of mission orchard construction and design; compile historic accounts of the mission orchard and fields; identify the types of plants that could have been grown in the orchard; study the genetic stock of old trees; and develop park interpretive programs. The studies provide the park with information needed to revitalize the mission period cultural landscape, recreate the historic setting, and provide accurate information to visitors. This article summarizes current research on the Tumacácori orchard and garden.

History of the Gardens and Orchards

The Spanish Colonial history of Tumacácori began when the Jesuit Order established a mission on the west side of the Santa Cruz River in 1752-1753. Previously, the Jesuits had a modest adobe church dedicated to San Cayetano on the east side of the river. After the Pima Revolt of 1751, the Jesuit mission was moved to the west side of the river and the patron saint changed to San José.

By 1757, a small adobe church measuring 60’ by 15’ was built at Tumacácori. The foundation of this church was discovered in 1934 when NPS archeologist Paul Beaubien excavated at Tumacácori. After the Jesuit Order was expelled from the New World the Franciscan Order took over the mission in 1773, and Tumacácori was designated a cabecera, or main mission, with Calabasas and Guevavi as visitas.

Construction of the present church began sometime between 1799 and 1802. The church was consecrated in 1822, but was never finished. Construction continued intermittently until the last priest departed for Magdalena, Sonora, in 1841. A small number of Indians continued to reside on the mission grounds and in the church. The consecrated sacramental furnishings were carried to San Xavier del Bac in Tucson, Arizona, when the remaining Indian population left during the harsh winter of 1848. After 1848, the church and convento began to deteriorate and were heavily damaged by treasure hunters. Although the site became a national monument in 1908, the church and grounds were not adequately protected until the National Park Service took over in 1916.

The Tumacácori Mission Grounds: Orchard or Garden?

The area presently called the mission orchard, or garden, lies to the east of the Franciscan convento. The area was separated from the convento and other agricultural fields by an enclosing wall. In an 1860 report to investors, William Wrightson, of the Santa Rita Mining Company, depicted the orchard as adjacent to the convento, observing that it enclosed about five acres.1 The area of the Tumacácori orchard and garden is actually 4.6 acres. This space focused the use of water to propagate fruit trees, vegetables, herbs, and possibly flowers, resulting in the transformation of the desert landscape into an earthly paradise.2

The common perception that the area east of the convento was primarily an orchard derives from historic accounts mentioning that peach, quince, pomegranate, mulberry, and fig trees still grew within the confines of the enclosing wall as late as 1849.3 An article published in the New York Times in 1891 added oranges, limes, and lemons to the list of fruit trees.4 Father Kino, Jesuit founder of the 1752 mission, also listed grapes, apricots, apples, pears and pecans in his description of Pimeria Alta mission gardens.5 Presumably, the Franciscans retained any domestic plants still growing when they took over Tumacácori in 1773.

In 1899, Frank N. Wright and Ricardo de Luna of Los Angeles camped near Tumacácori. De Luna “suggested watching the mission orchard by moonlight as a good way of getting deer; they did and they shot a deer who was feeding on fallen apples. The trees were old and scraggly then, but still bearing.” Other visitors noted pomegranate, pears, peaches, apples and apricots in the garden during the late 1880s and early 1900s.6 In 1934, custodian George Boundey wrote that his wife canned fifty quarts of “the peaches Father Kino introduced to this country.”7 Peach trees persisted along the acequia and in the garden until 1936 when the acequia stopped flowing and the land was cleared for cotton.

Travelers’ accounts mention fruit-bearing trees, but do not mention vegetable or herb gardens. This is not surprising because well established fruit trees can survive without tending for some time, and the 1849 accounts were made only one year after the last remaining Indians departed for San Xavier del Bac. Medicinal herbs, cooking herbs, and vegetables require more attention and had probably disappeared by the 1849 visit. Father Kino’s list of plants carried to Jesuit Missions suggests that “cabbages, melons, watermelons, white cabbage, lettuce, onions, leeks, garlic, anise, pepper, mustard, mint, Castilian roses, and white lilies” were under cultivation at Tumacácori.8 Some of these plants are not as noticeable or enticing as standing fruit trees, and there was probably little evidence to warrant mention in historic accounts. So, were there both orchards and gardens established within the area often referred to as the Tumacácori Orchard?

The layout and design of Spanish mission gardens and orchards in the New World developed in the 8th century from an Andalusian form of monastic gardens, but were influenced by Islamic garden design, sense of aesthetics, horticultural knowledge, and irrigation technology. The transference of Islamic landscapes and garden sensibilities to Spain is evident in Valencia and Seville.9 The Islamic design of agricultural spaces usually incorporated gardens and orchards into one defined area, but sometimes gardens and orchards did have separate enclosing walls. In the New World, border plants, including quince and pomegranate, may have been used to divide space, as can be seen today in Mexico. The enclosing wall at Tumacácori served to protect fruit trees, beds of medicinal and cooking herbs and possibly flowers, or sensitive and rare vegetables. The space was an important part of the Spanish institutionalized cultural landscape at Tumacácori and other missions.

We do not know the full variety of plants grown within the garden and orchard. Pollen analysis has been inconclusive due to poor soil preservation.10 Despite their ubiquity at Pimeria Alta missions, no site plans of the Jesuit or Franciscan mission gardens and orchards have been located. All that can be said is that both orchards and gardens once existed within the enclosed area east of the convento. The enclosed 4.6 acre area will be called the mission garden here, but keep in mind that it was also an orchard.

The Tumacácori Garden Walls

Aerial photographs from 1936 show the original configuration of the garden walls. The square tree line marked the extent of the garden; today, these trees are some of the tallest and oldest on the mission grounds. The north wall of the garden was destroyed sometime after 1949, but the southeast corner was avoided during plowing of the surrounding agricultural fields.

Remnants of the garden walls, described in travelers’ accounts and surveyed by archeologist Paul Beaubien in 1934, formed a rough orthogonal shape on three sides. The fourth side (west) connected to the north wall by a diagonally-indented fifth wall, which eliminated the northwest corner. The south and west sides incorporated walls of other buildings in places, resulting in double walls.11 This diagonal wall is a perplexing aspect of the garden. Why was the northwest corner diagonal rather than squared? Did this wall reduce construction costs, or does it represent a purposeful design choice related to planting or some other function?

The diagonal wall reduces the length of the entire wall by 80 feet, minimally decreasing the amount of labor and materials needed to construct the northwest corner. If reducing construction costs was a consideration, however, then why not put diagonal walls in the other two available corners? At Tumacácori, funds and materials often ran out during construction episodes, forcing changes in the design of the church and convento.

Is it also possible that the priests were in a hurry to construct the wall? The wall would have been useful for defensive purposes, and Apache Indian attacks were always imminent. Perhaps the northwest corner was truncated to save time during construction of the garden wall.

An equally plausible explanation for the northwest corner wall is that the interior space along the wall provided a micro-climate for sensitive plants. A micro-climate is an environment that changes the usual climate and soil characteristics of a location. Most gardens and orchards contain a range of micro-climatic zones. Sunlight, southern and northern exposures, wind directions, and low spots where cold air and water pool, all contribute to the type and function of micro-climates. Micro-climates make it possible to plant species that are not standard for a particular area.

In the American Southwest, from April 20th to September 20th the sun rises in the northeast and has a southerly declination, or arc, before setting in the northwest. The sun is in the northwest sky during hot summer afternoons. Thus, the interior of the northwest corner would have offered shade during the hottest time of the year, and would be warmer during winter months. The three-sided corner could have provided an additional micro-climate for certain trees, vegetables, and herbs that require moist soils and lower temperatures. Shallow rooted plants require soil with high moisture content and low temperature. Vegetables and herbs that may have benefited from the micro-climate of the northwest corner include tepary beans, chilies, lettuce, cucumber, melons, tomatillos, tomatoes, cilantro, oregano, and possibly potatoes.

The acequia once passed through this northwest corner wall, suggesting that the wall might have been angled to fit the contour of the land for irrigation ditches that passed through it but this hypothesis is not testable, since agricultural activities have destroyed any traces of the acequia here and have modified land contours.

Archeological Investigations of the Garden Walls

Although many travelers visited and described the mission after it was abandoned, Wrightson is the only one to note the garden wall. In 1860, he remarked that the orchard was “surrounded by a cahone [adobe?] wall.”12 The garden wall was made of adobe, as Wrightson surmised, although archeological investigations along the south and east garden wall found great variability in construction technique. Construction began with the excavation of a trench that was filled with mud and river cobbles. Adobes were then laid on top of the upper course of the river-cobble foundations. Remnants of adobe walls and foundation stones were mapped in 1934 and photographed in 1949. Park staff recalled standing, but eroded, adobe walls as late as the 1970s.

Archeological investigation of the garden wall began in 2004 with assistance from the NPS Western Archeological and Conservation Center. Work began on the south garden wall where river-cobble foundation stones are exposed at the surface. Two 3’ x 3’ units were excavated adjacent to the foundation stones; one along the interior and another along the exterior. No cobbles were found in the unit along the exterior of the wall, but the excavation of the interior unit revealed cobbles 20 cm below the ground surface. The cobbles along the interior appear to be a ledge or step in the lower sub-surface portion of the foundation.

It is unclear why the cobble foundation for the south wall was constructed with a ledge. The ledge may have supported buttresses to help strengthen the wall. An example of the use of buttresses to strengthen a garden wall was discovered in the 2004 excavations at San Agustine, in Tucson. Buttresses were placed at regular intervals along the interior of the wall.13 As more units were excavated along the interior of the Tumacácori south garden wall, however, the rock ledge was found to continue along the full extent of the exposed 60 feet of foundation.

If the cobble ledge isn’t a buttress, could it be the edge of the foundation for an earlier wall? The cobble foundation showing at the surface appears to be tied into the lower cobble ledge however. If all of the cobbles are part of one foundation, the south wall foundation is 4.5 feet wide, which is an extremely wide foundation for a simple garden wall.

The construction method for the foundation of the east garden wall significantly differs from the south wall. The east wall foundation is only about 2 feet wide, and was constructed using the core and veneer technique of placing large river cobbles on the sides and filling the space between with smaller cobbles and mud. In contrast, the foundation stones for the south wall are size-sorted and the core and veneer technique was not used. The east wall foundation stones are not exposed at the surface, instead they are covered by a mound of adobe melt.

Photos of the east wall taken in 1949 show an eroded, but standing, adobe wall approximately 3 feet high. The north orchard wall was destroyed by agricultural activities before the park acquired the land and the photo of the north side of the garden shows only foundation stones. These remnants of the north wall resemble the south wall prior to the 2004 excavations, and suggest that the adobe bricks of the north and south wall eroded at the same rate. Either the south wall adobe bricks eroded faster than the east wall, or the east wall was constructed after the south wall and was not exposed to the elements as long. The most plausible explanation is that the north and south walls were built at a different time than the east wall. The differences in foundation size, construction technique, and rates of adobe erosion can be explained by repairs to wall foundations following floods and by differential erosion of the walls.

The south and east walls may have been repaired multiple times. Although the garden area does not flood today, high intensity floods were frequent in the past. It is probable that the ledge of the south wall foundation represents an attempt to strengthen the south wall by providing a footing or toe for the foundation on which the adobe wall was built. Perhaps, at some time in the past, the south wall was perpendicular to the flow of rushing water, causing increased adobe erosion and subsidence of the wall, requiring it to be rebuilt. Subsequent flooding and wind erosion destroyed the adobes of the south wall after it was rebuilt. The east wall remained intact longer because it was parallel to the flow of rushing water during floods.

The original height of the garden wall cannot be determined from the current physical evidence. In 1849, the wall is described as being “high,” but how high? The walls were probably higher than four feet to keep out animals, raiding Apache Indians, and to create a micro-climate for plants. A photo of the San Agustine mission, in Tucson, shows a garden wall that appears to be 4 to 6 feet high.14 The width of the wall foundations imply that the garden wall at Tumacácori was around the same height.

The Age of the Garden Wall

We do not know when the garden wall was built or when plants were first established in the garden. In 2004, trenches were excavated to locate the garden wall where it meets the convento at its southwest corner, but the trenches revealed disturbed soil and no intact foundations. It is possible that portions of the garden wall date to the Jesuit period. It is more probable that a small garden enclosure was built near the southeast corner of the present garden wall, just east of the convento, sometime between 1770 and 1800 when modifications of the Jesuit complex were completed by the Franciscans. The larger 4.6 acre enclosure was probably built during the flurry of construction activity that took place from 1802 to 1828.15

The acequia

The mission acequia is a canal that was constructed to bring water from the Santa Cruz River to a network of irrigation ditches that supplied water to the mission farm fields, orchard, and gardens. The acequia ran from the south end of the mission, where it picked up water from the Santa Cruz, to the north end of the mission where it re-entered the river. Eighteenth and nineteenth century accounts of the mission attribute the beauty and prosperity of the mission gardens and orchard and the high state of cultivation of the farm fields to the network of irrigation ditches fed by the mission acequia.16 The acequia carried water through the park until 1938, when new wells significantly lowered the local water table.

Archeological investigations at the park have identified few irrigation features. The original acequia has been largely obliterated by modern farm fields and some segments were straightened and reinforced with concrete for modern use. The location of the acequia can be inferred from historic maps, descriptions, and photographs. Only one acequia is known, but there were probably multiple acequias that helped water thousands of acres.

The Compuerta

Wrightson noted that “the acquia [sic] passes through this [the garden wall], and here is the remains of a washing vat and bathing place.”17 The washing vat is the diversion box or compuerta located 14’ inside the south orchard wall. This feature was first identified by Beaubien in 1934. The structure measures 4’1” wide by 13’10” long, with a 3” dip in the ends of the north and south floor. It is constructed of fired adobe bricks and hydraulic lime plaster with a crushed brick (cacho pesto) finish. Although its function is unknown, the feature probably served to impound water by constricting and slowing ditch flow in order to create sufficient head for lateral ditches that fed gardens and orchard trees

The compuerta may have also served as a lavandaria, or laundry tank. The lavandaria was a common element of mission gardens in the Pimeria Alta and Alta California.18 In 1849, Forsyth described the feature as one of the “beautiful baths,” suggesting there was more than one compuerta.19 Although only one has been found, it is probable that numerous diversion boxes were needed along the acequia madre to feed lateral ditches for wheat and corn fields.

Visions of an Active Garden and Orchard at Tumacácori

Staff at Tumacácori NHP are presently working to re-establish a fruit tree orchard within the original garden wall. European style orchards and fields planted by Spanish missionaries were part of the cultural transformation of the local landscape. Establishing the orchard is the first step in achieving the park’s goal to recreate the historic mission cultural landscape including gardens, orchards, fields, and possibly livestock.

This vision of an active garden and orchard began in the 1920s and 1930s, but there are few details of attempts to re-establish plants. In a 1923 letter to NPS Director Stephen Mather, Southwest Monument Superintendent Frank Pinkley wrote that:

Governor Hunt has donated a hundred or more cuttings of grapes, olives, figs, and peaches, which we have in trenches where they are starting nicely and which we will move to their final location as soon as we have our windmill, tank, and water system installed. He has promised us anything in the way of cuttings we may need to restore the mission grounds.20

There are no records on how the cuttings donated by Governor Hunt fared. In 1973, Mrs. King, whose family resided near the mission in the late 1800s and early 1900s, said she had cuttings of the “original fruit trees (peaches, figs, and pomegranates) in her yard in Tucson.”21 Recent attempts by park staff to locate the trees were unsuccessful.

Today, the search for cuttings of heirloom fruit trees continues with the Kino Fruit Trees Project, led by Jesus Manuel Garcia Yánez (Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum) and Robert M. Emanuel (University of Arizona).22 This project is carrying out research to locate, propagate, and re-establish historically-accurate fruit cultivars. Trees that can be traced back to genetic stocks of Old World trees introduced 150-300 years ago have been identified in mission orchard communities in Sonora, Mexico; on the University of Arizona campus; at Quitobaquito Springs in Organ Pipe NM; and at historic houses and backyards of private residences. Cuttings and seeds are being propagated at various farms and nurseries throughout southern Arizona. Hopefully, stock from historic tree cuttings will be transplanted to the Tumacácori garden area within the next 3 to 5 years.

All ambitious projects begin with a vision. For years, park staff have nourished a vision of an active garden and orchard that allows visitors to experience an aspect of mission life. Re-establishing the mission orchard and garden is a formidable task, but reintroducing Spanish-era plant stocks will contribute to the interpretive, educational, and preservation objectives of Tumacácori NHP. Our hope is that one day a visitor can walk out of the convento and into the green earthly paradise of the mission orchard and garden. Perhaps visitors will be able to pick a peach and savor the sweetness of Father Kino’s labors in the Pimeria Alta.

By Jeremy Moss

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank David Yubeta, and Superintendents Ann Rasor and Lisa Carrico for their support during this project. Special thanks goes to Karen Mudar for her editorial advice and assistance. Most of all I thank Frank “Boss” Pinkley for his boundless energy and will to preserve America’s special places.

Notes/References Cited

1 William Wrightson, Second Annual Report, Santa Rita Mining Company, March 19, 1860, 14-15.

2 James Dickie, “The Islamic Garden in Spain” in E. MacDougall and R. Ettinghausen, eds., The Islamic Garden, Dumbarton Oakes and the Trustees for Harvard University, Washington, DC, 1976, 89-105.

3 John R. Forsyth, Journal of a Trip from Peoria, Illinois to California on the Pacific in 1849, Peoria Public Library, Peoria, Illinois, n.d., 75. Lorenzo D. Aldrich, A Journal of the Overland Route to California and the Gold Mines, Alexander Kirkpatrick, Printer, Lansingburgh, NY, 1851, 29-30. Benjamin Hayes, “Diary of Judge Benjamin Hayes’ Journey Overland from Socorro to Warner’s Ranch from October 31, 1849 to January 14, 1850,” in Owen C. Coy, The Great Trek, Powell Publishing Co., San Francisco, 1931, 247. Wrightson, 1860, 14-15.

4 New York Times, March 1, 1891, mentions fruit trees on the mission grounds. The passage describing the trees and “gardens of vegetables and plants” is written in past tense suggesting the author used conjecture and the plants were not actually seen in 1891. No specific location for the plants is given.

5 Herbert Bolton, Kino’s Historical Memoir of Pimeria Alta, Arthur Clark Company, Cleveland, OH, 1919, 89, 265.

6 Sallie Brewer, TUMA Fact Files, 1944. Brewer interviewed Frank Wright on September 6, 1944. She also interviewed Jose Wise, Juan Mendez and Nacho Flores. Joe Wise remembered pomegranates in the 1880s; Juan Mendez mentioned pears, peaches, pomegranates, and apples in the early 1900s; Nacho Flores remembered peach and apricot trees along the acequia, and a few trees in the mission garden area.

7 George Boundey, Superintendent’s Monthly Report, NPS, WACC, 1934.

8 Kino, in Bolton 1919, 89, 265.

9 Mildred Stapley Byne and Authur Byne, “Spanish Gardens and Patios,” The Architectural Record, 1924, 115-116. William W. Dunmire, Gardens of New Spain: How Mediterranean Plants and Foods Changed America, University of Texas Press, Austin, TX, 2004, 13-14. Thomas F. Glick, Islamic and Christian Spain in the Middle Ages, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 1979, 54.

10 Soil samples from the garden were recently analyzed for plant pollen. The results showed that wet-dry cycles from irrigation and plowing have damaged pollen grains. Besides native grasses, Arizona walnut was identified. Pollen analysis of soils from excavations in the plaza area south of the church identified corn, wheat, melons, squash, watermelon, beans, lentils, cotton, and peaches. Other native foodstuffs found include mesquite beans, saguaro cactus, prickly pear cholla, ocotillo, native walnut, amaranth, netleaf hackberry, and graythorn seeds. Huckell in Fratt 1979, 212.

11 Paul Beaubien, Excavations at Tumacácori, 1934, NPS Southwest Monuments Report, 1937.

12 Wrightson 1860, 14-15.

13 Homer Theil, (Desert Archeology, Tucson) personal communication.

14 Carlton Watkins photo, AHS# 18233, Arizona Historical Society research library, Tucson.

15 James Ivey, “Here was Troy: Architectural and Archeological History of the Tumacácori Missions,” NPS Historic Resources Study (draft), Santa Fe, NM, n.d.

16 J. Ross Browne, Adventures in Apache Country: A Tour Through Arizona and Sonora, 1864, University of Arizona Press, 1974.

17 Wrightson, 1860, 14-15.

18 Tonia Horton, Tumacácori National Historical Park Cultural Landscape Study, NPS, 1998, 33.

19 Forsyth, 1849, 74.

20 Frank Pinkley, Superintendent’s Monthly Report, NPS, WACC, December 1923.

21 Author Unknown, TUMA Fact Files, 1973.

22 Jesus Manuel Garcia Yánez and Robert M. Emanuel, The Kino Fruit Trees Project: Phase I (January-October 2004), (NPS, CESU, 2005) 3-4.