Like ecologists, environmental historians understand change in terms of numerous variables interacting over time, albeit with more emphasis on the human role.

Key words: environmental history, interdisciplinary research, “the long now,” resource management, Rocky Mountain National Park

HISTORIANS AND SCIENTISTS ENJOY SURPRISES—that part of the story that is unexpected and unpredictable. Surprises are reminders that life is uncertain and that inquiry is a process of questioning conventional assumptions. So here is a surprise: Rocky Mountain National Park, that alpine gem in Colorado, is a historical park. It is true that Rocky Mountain is not the same kind of park as Gettysburg National Military Park or Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument. It is true that the park’s enabling legislation of 1915 calls for “the preservation of the natural conditions and the scenic beauties thereof” (Rocky Mountain National Park Act, 38 Statute 798). It also is true that Rocky Mountain visitors come to experience bugling elk, waterfalls, wildflowers along Trail Ridge Road, Longs Peak, aspen in fall colors, and much more. And yet, none of these wonderful truths about a magnificent park negates another irreducible reality that is no less wondrous: Rocky Mountain National Park is a historical park.

For scientists, the park’s history is an open secret. Much research on the park addresses site-specific issues such as the number of elk, the decline of willows, the absence of beavers, the chemical condition of water flowing from a lake, or the deposition of sediment in a valley. Accordingly, researchers necessarily ask historical questions: What happened here? What caused this? What conditions prevailed in the past? Scientists, furthermore, explicitly recognize their work as historical. David Cooper, whose consultations with park staff on wetlands and alpine flora go back decades (e.g., Kaczynski and Cooper 2014), insists that historical questions should be among the first that a researcher asks. Jill Baron, who has collected more than 30 years of data on nitrogen deposition at Loch Vale (e.g., Baron 2006), likes to quote William Cronon that ecology is a historical science. This focus on floral, faunal, and geological history merges with ancient human history in the discipline of archaeology. Bob Brunswig has surveyed hundreds of archaeological sites dating back to when the Pleistocene glaciers and ice fields began their retreat (Brunswig 2007).

For their part, environmental historians who work in Rocky Mountain National Park are better equipped than ever to recognize the history, human and nonhuman, in the park’s nature. Much as ecology has become more historical, scholarly history has become more ecological (Fiege 2011). Like ecologists, environmental historians understand change in terms of numerous variables interacting over time, albeit with more emphasis on the human role. How did human history shape forests, streams, and wildlife? How did people’s experience of the landscape shape their history? Like ecologists, environmental historians also seek to understand change through multiple spatial and temporal scales. The concept of “the long now,” for example, connects past, present, and future in a single analytical frame (Robin et al. 2013).

An environmental historian working in the park soon discovers affinities with scientists. A conversation with David Cooper about tree trunks and animal bones at the bottom of a subalpine bog evokes shared feelings of wonder that such traces of a lost world could survive into the present. As the biogeographer Jason Sibold holds forth on wildfire history as revealed in burn scars on trees (e.g., Sibold et al. 2006), he poses questions about the potential of archival documents to yield additional insight into the subject. During a discussion of alpine lake sediments, Jill Baron emphatically affirms the historian’s observation that in geological time, the birth of the lake some 14,000 years ago just happened. Sometimes the affinities come to light on backcountry trips. Snowshoeing through the silence and shadows of an 800-year-old grove of subalpine fir, the historian remarks that the trees are medieval. “Yes!” Baron replies, and she reveals that she once considered majoring in medieval studies.

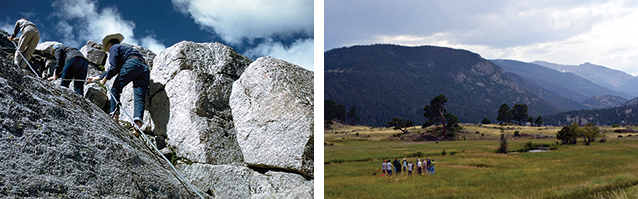

Left: NPS Photo; Right: Photo courtesy Public Lands History Center, 2014

A range of recent projects addresses Rocky Mountain National Park’s historical nature and suggests the potential of environmental history to augment the work of scientists in support of management. A study of climbing on Longs Peak explains changes in mountaineering in relationship to shifting environmental conditions, thereby providing knowledge essential to the management of crowds in a designated wilderness area (fig. 1; Alexander and Moore 2010). Histories of invasive exotic plants document their spread and the results of efforts to control them, thus informing the decisions of park staff responsible for protecting native species (e.g., Blankers 2014). The Parks as Portals to Learning partnership unites park staff with Colorado State University faculty and students in a workshop that will interpret the historical human presence, including elk and vegetation management, in Moraine Park (fig. 2). Soon to be offered in book form, the lecture “Elegant Conservation” shares a concept of resource stewardship grounded in environmental history methodology (Fiege 2015). In February 2010, park staff, scientists, and historians traveled on snowshoes through the Kawuneeche Valley, located on the west side of the park. The outing was unusual not only because of its inclusion of historians, but also because the purpose of the trip was to see evidence of ecological disturbance and to discuss how history might help the park manage and interpret the valley. The eventual product of that outing was a detailed study of the valley’s environmental history (Andrews 2015).

To recognize Rocky Mountain National Park as a historical park is to imagine a better future for it and other parks. At Rocky Mountain, environmental historians can continue to offer knowledge and skills useful to management and interpretation (e.g., Higgs et al. 2014). They can assist scientists in the formulation of research questions. They can provide documentary evidence to help answer those questions and to convey scientific findings. They can narrate the great story of how the park landscape and all that it contains came into being and changed over time. And as skilled writers and communicators, they can offer stories about scientists and science to the public.

Most importantly, acknowledging that all national parks are historical can help the National Park Service realize the potential of two visionary documents, Imperiled Promise (Whisnant et al. 2011) and Revisiting Leopold (National Park System Advisory Board Science Committee 2012). Both assert that the agency’s traditional distinction between nature and culture, and natural and cultural resources, has outlived its usefulness. Among other problems, this simplistic division leads natural resource managers to think about history primarily in terms of the conflict-oriented compliance required by cultural resource law. Because of its commonalities with ecology and other natural sciences, however, environmental history is positioned to bring history into parks in a manner that bridges the classic “two cultures” divide.

Looking ahead to Rocky Mountain National Park’s second century and the 2016 celebration of the National Park Service centennial, an alternative future is within reach. In that time to come, visitors will experience Rocky Mountain’s natural wonders, but they also will have the opportunity to discover how park resources got there in the first place, and how people perceived and managed those marvelous things. Thus equipped, visitors will be able to look forward and imagine the conditions under which the park still might inspire wonder—or not—in the years ahead.

Literature cited

Alexander, R., and C. Moore. 2010. People and nature on the mountain top: A resource and impact study of Longs Peak in Rocky Mountain National Park. Public Lands History Center, Colorado State University, Colorado, USA.

Andrews, T. G. 2015. Coyote Valley: Deep history in the high Rockies. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

Baron, J. 2006. Hindcasting nitrogen deposition to determine an ecological critical load. Ecological Applications 16(2):433–439.

Blankers, E. 2014. Cirsium arvense, Canada thistle. Environmental History Exotics Management Briefs. Public Lands History Center, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA.

Brunswig, R. H. 2007. Paleoindian cultural landscapes and archaeology of north-central Colorado’s southern Rockies. Pages 261–310 in R. H. Brunswig and B. L. Pitbaldo, editors. Frontiers in Colorado paleoindian archaeology: From the Dent Site to the Rocky Mountains. University Press of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado, USA.

Fiege, M. 2011. Toward a history of environmental history in the national parks. The George Wright Forum 28(2):128–147.

———. 25 March 2015. Elegant conservation: Rediscovering a way forward in a time of unprecedented uncertainty. Wallace Stegner Lecture, Montana State University, Bozeman, Montana, USA.

Higgs, E., D. A. Falk, A. Guerrini, M. Hall, J. Harris, R. J. Hobbs, S. T. Jackson, J. M. Rhemtulla, and W. Throop. 2014. The changing role of history in restoration ecology. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 12(9):499–506.

Kaczynski, K., and D. J. Cooper. 2014. Post-fire response of riparian vegetation in a heavily browsed environment. Forest Ecology and Management 338:14–19.

National Park System Advisory Board Science Committee. 2012. Revisiting Leopold: Resource stewardship in the national parks. National Park System Advisory Board, Washington, D.C., USA. Available at https://www.nps.gov/calltoaction/PDF/LeopoldReport_2012.pdf.

Robin, L., S. Sörlin, and P. Warde. 2013. The future of nature: Documents of global change. Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut, USA.

Sibold, J. S., T. T. Veblen, and M. E. González. 2006. Spatial and temporal variation in historic fire regimes in subalpine forests across the Colorado Front Range. Journal of Biogeography 33:631–647.

Whisnant, A. M., M. L. Miller, G. B. Nash, and D. Thelen. 2011. Imperiled promise: The state of history in the National Park Service. Organization of American Historians, Bloomington, Indiana, USA.

About the author

Mark Fiege is a professor of environmental history with the Public Lands History Center, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado.

Download: PDF of this article

This article published

Online: 6 May 2016; In print: 25 March 2016

URL

https://www.nps.gov/ParkScience/articles/parkscience32_2_76-78_fiege_3843.htm

Suggested citation

Fiege, M. 2016. Nature, history, and environmental history at Rocky Mountain National Park. Park Science 32(2):76–77.

This page updated

5 May 2016

Site navigation

• Back to Volume 32, Number 2

• Back to Park Science home page

Last updated: February 15, 2026