NPS

November 28, 2016 - On the surface, mountain lions in the Santa Monica Mountains are doing well, surviving and reproducing at healthy rates. However, recently published research predicts that there could be serious challenges to this population’s long-term survival. Using a unique combination of geographic, genetic, and demographic data, researchers at Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, UCLA, UC Davis, and Utah State University modeled how the mountain lions might fare under different future scenarios.

NPS

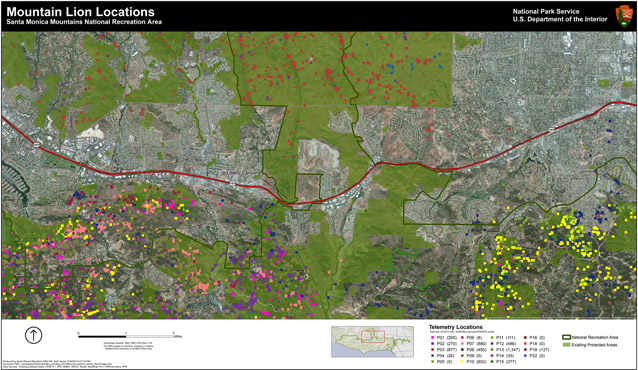

One scenario studied is what will happen if the mountain lions continue as they are. Besides appearing relatively health, this status quo scenario includes a high degree of isolation. Major freeways and developed areas represent major barriers to the movement of mountain lions and other wildlife to and from the Santa Monica Mountains. Since 2002, National Park Service biologists have tracked over 50 mountain lions in the region and documented only one instance where a subadult male from the Simi Hills (identified as P-12) crossed the 101 Freeway to enter the Santa Monica Mountains. Only one male and one female (P-32 and P-33) have been confirmed leaving, also by crossing the 101 Freeway.

NPS

With isolation comes inbreeding and a subsequent loss of genetic diversity. At a certain point, low genetic diversity leads to inbreeding depression, whereby populations can no longer survive and reproduce at normal rates. The Park Service has already documented many cases of close inbreeding. For example, the male that managed to migrate into the population from the Simi Hills later mated with two of his daughters and a granddaughter, partially undoing his initial positive genetic contributions. As it stands, the genetic diversity of the Santa Monica Mountains population is among the lowest ever documented for the species. Only the Florida panther population experienced lower genetic diversity, and nearly went extinct as a result (panthers and mountain lions are the same species).

The researchers incorporated the poor survival and reproduction rates attributed to inbreeding depression in Florida panthers into their model for mountain lions in the Santa Monicas persisting in isolation. The results indicated that if the mountain lions remain cut off from other populations by freeways and development, they will face a 99.7% chance of extinction within 50 years. Much shorter extinction timeframes were found to be likely.

NPS

Even if isolation were not to lead to a loss of genetic diversity, the model suggested that a 15-22% chance of extinction would remain due to the population’s small size. It would only take a couple of car accident or rodenticide deaths of key individuals, for instance, to disrupt breeding and lead the population into a downward spiral.

At the same time, other modeled scenarios indicate that extinction is far from a foregone conclusion. Just a small boost in connectivity between mountain lion habitat in the Santa Monica Mountains and neighboring areas could protect against both a loss of genetic diversity and against other risks that plague small populations. Making it possible for even just one mountain lion from elsewhere to join the population every two years, would bring extinction risk down dramatically to just 2.4%. The ability of young mountain lions to disperse to other areas would further help by reducing the chances of inbreeding.

NPS

A solution in the form of a wildlife corridor across the 101 Freeway at Liberty Canyon is currently being drafted by Caltrans. The corridor would connect the Santa Monica Mountains with the Simi Hills just to the north at a spot where mountain lions have attempted to cross in both directions. Save LA Cougars, a private fundraising campaign, is raising money for the project. Importantly, such a crossing would benefit not only the mountain lions that need it so urgently, but also all kinds of other species that are stuck on one side or the other of the colossal partition in the landscape that is the 101 Freeway.

NPS (view on Flickr)

More background and results from the new study, published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B, can be found in this Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area news release. General information and links about mountain lions and mountain lion research in the Santa Monicas are also available from the national park’s mountain lion webpage.

Prepared by the Mediterranean Coast Inventory and Monitoring Network.

Last updated: March 15, 2017