Last updated: April 2, 2025

Article

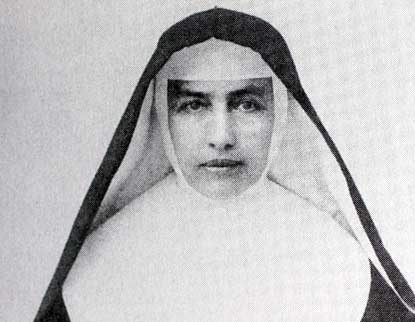

A Place of Care: Mother Marianne Cope and the Kalaupapa Cultural Landscape

Hawaii State Archives

Mother Marianne passed away in 1918. Almost a century later in 2005, Pope Benedict XVI beatified Mother Marianne and made her a saint, a holy act to signify her devotion to the patients for whom she cared on the island of Molokai. Today, the life and actions of Mother Marianne demonstrate and reflect not only the saintly devotion dedicated to Hawaiian patients but also the changing historical cultural landscape on modern-day Kalaupapa National Historical Park.

NPS Photo

In 1873, Joseph De Veuster, commonly known as Father Damien, arrived to care for 600 leprosy patients and initiated the construction of care facilities throughout the peninsula. Mother Marianne and her group of St. Franciscan Sisters arrived a decade later. As she stated at the time:

I am hungry for the work and I wish with all my heart to be one of the chosen ones, whose privilege it will be to sacrifice themselves for the salvation of the souls of the poor Islanders.... I am not afraid of any disease, hence, it would be my greatest delight even to minister to the abandoned ‘lepers.’ [1]

The influence of Mother Marianne, in addition to her group of St. Franciscan sisters and Father Damien, cannot be understated for this affected community. With the settlement and patient-care established by the 1880s, development of the land helped create the cultural landscape on the peninsula.

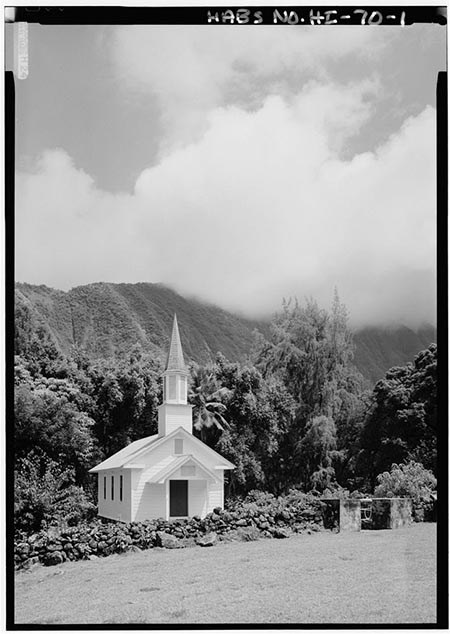

Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS HI-70), Library of Congress

Approximately 1,000 cattle were imported as a source of beef and dairy. Both patients and caregivers began growing sorghum and alfalfa for cattle, papaya and pumpkins for hogs, and began planting a variety of trees that included at least 1 Hala, 45 Japanese plum, 50 Eucalyptus, 50 avocado, date palm, hibiscus, and pomegranate trees.

The second major development occurred on the western side of the peninsula at Kalaupapa, marking another dramatic change for the cultural landscape. During this period, the Bay View Home for the Aged and Blind was built, a cemetery was constructed along the Kalaupapa coastline, and fences were erected to deter animals from damaging graves. Patients and caregivers began growing taro, potatoes, and vegetables and planted about 300 coconut trees. By 1918, most of the grounds had been graded and planted.

NPS Photo

Up until her death, Mother Marianne played a fundamental role caring for the patients as well as assisting with the development of Bishop Home and the surrounding landscape. She planted fruit trees and flowering shrubs and plants. Mother Marianne saw the practical value of the fruit as a food source for the home, and she understood the aesthetic value of the colorful flowers that helped cheer the spirits of the sick. In 1918, Mother Marianne passed away at Kalaupapa, leaving a landscape to tell her legacy of care and support for patients with what is now known as Hansen's disease.

NPS Photo

Managed in joint cooperation between the National Park Service and Hawaii Department of Health, the Kalaupapa National Historical Park and its historical cultural landscape shape the isolation story of patients, patients’ families, and caregivers alike. Mother Marianne Cope exemplifies a life dedicated to Kalaupapa, and her story illuminates the cultural landscape experienced today.

[1] The Vatican, Biography Marianne Cope (1838-1918), http://www.vatican.va/news_services/liturgy/saints/ns_lit_doc_20050514_molokai_en.html

Additional Reading

- Rygh C and Tamimi L. 2011. Kalaupapa and Kalawao Settlements: Cultural Landscape Inventory, Kalaupapa National Historical Park, National Park Service. Cultural Landscape Inventories. 975012. NPS Pacific West Regional Office. Pacific West Regional Office/CLI Database.

- Linda W. Greene, National Park Service, Kalaupapa National Historical Park, Historic Resource Study – Exile in Paradise: The Isolation of Hawai’i’s Leprosy Victims and Development of Kalaupapa Settlement, 1865 to Present.

- National Park Service, Kalaupapa National Historical Park, Mother Marianne Cope and the Sisters of St. Francis.

- National Park Service, Kalaupapa National Historical Park, History & Culture.

- CNN, Mother Marianne becomes an American saint.

- The Vatican, Biography Marianne Cope (1838-1918).

- Homily of His Holiness Pope Benedict XVI, For the Canonization of the Blessed, 21 October 2012.