Last updated: November 9, 2018

Article

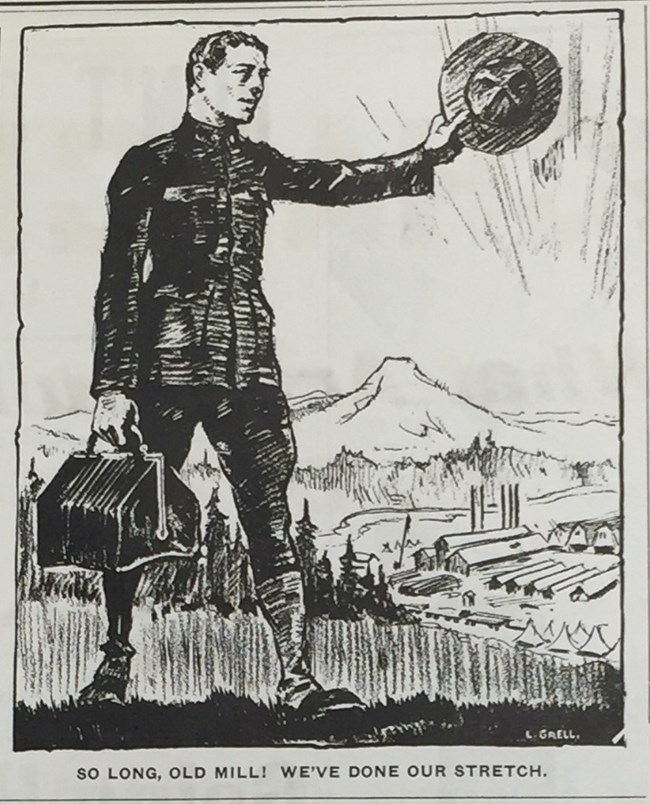

Artist Louis Grell and the Vancouver Spruce Mill

NPS Photo / FOVA 235608

At the outbreak of World War I, Grell returned to the United States, where he worked as a set designer for Broadway plays in New York City. In 1916, Grell was recruited to become an art instructor at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts, one of the United States’ most prestigious art academies at the time. There, he taught a young Walt Disney, who was then a high school student attending art classes at night.

In April, 1917, the United States entered World War II. Like many men of his generation, Grell placed his career on pause when he entered military service in 1918. In late October, he arrived at Vancouver Barracks, having been assigned to the US Army’s Spruce Production Division.

At Vancouver, Grell encountered the massive Vancouver Spruce Mill. The Spruce Production Division’s lumber camps, scattered throughout the Pacific Northwest, sent spruce lumber here, where it was milled and sent to Allied aircraft manufacturers.

NPS Photo

Photo provided courtesy of Richard Grell.

“Have been busy in the office classifying the new men since I have been here. Are 2 weeks in camp before we are able to go out. Then we shall be distributed around to other camps all according to our ability and former profession. Am not a great friend of this life and hope the war will soon be over. The country around here is very beautiful.”

In this correspondence, Grell is probably describing the typical induction process for a new recruit of the Spruce Production Division (SPD). Upon arrival, troops were organized into squadrons of 150 men. Soldiers would then go through a three-week SPD training, a modified form of military basic training that included physical training and infantry drills, as well as lectures and instruction on airplanes in war, field fortification and topography, manual guard duty, and sanitation. After training, troops would remain in Vancouver until they were needed in forest mills and camps.

The Vancouver Spruce Mill ran three shifts each day and employed around 5,000 men. Soldiers lived in cantonments and squad tents near the plant. Because men were working in three eight-hour shifts, kitchens, bakeries, mess halls, recreation rooms, and other facilities had to operate 24 hours each day. At the Spruce Mill, Grell would have found a constantly-bustling hive of activity.

However, on November 11, 1918, just as his training period was ending, armistice was signed and the war was over. Instead of “going out” to a forest camp as he had written to his sister, Grell remained in Vancouver. In the last part of 1918 and first months of 1919, Vancouver Barracks was the site of a significant demobilization operation, as SPD soldiers stationed throughout Oregon and Washington gathered at Vancouver Barracks, where they were discharged and sent home. Grell remained in Vancouver at least through January 1919, as evidenced by his artwork from this period, which appears in issues of the Straight Grain, the short-lived official newspaper of the Spruce Production Division at Vancouver Barracks.

The Straight Grain’s first issue was released on October 26, 1918, but Grell’s first appearance in its pages occurred in the November 23, 1918, issue. Here, he is listed as a member of the paper’s two-man art department. While none of his drawings appear in this issue, numerous Grell illustrations appear in the following issues until the paper’s final issue on January 4, 1919.

The Straight Grain described itself as “the soldiers’ own paper.” It was designed not just to spread official information about the post, but also to “cheer up” soldiers with jokes, cartoons, and stories created by the soldiers themselves. Grell’s illustrations and cartoons in the Straight Grain, while often done in a more serious and realistic style than other soldiers’ artistic contributions, are true to this mission, and are humorous, encouraging, and inspiring.

After his discharge from the Army, Grell returned to Chicago and worked throughout the United States as a noted muralist and painter. See more works by Louis Grell and learn more about his biography at www.louisgrell.com

To see the illustrations that Grell provided for the Straight Grain, see the gallery below.

The Straight Grain described itself as “the soldiers’ own paper.” It was designed not just to spread official information about the post, but also to “cheer up” soldiers with jokes, cartoons, and stories created by the soldiers themselves. Grell’s illustrations and cartoons in the Straight Grain, while often done in a more serious and realistic style than other soldiers’ artistic contributions, are true to this mission, and are humorous, encouraging, and inspiring.

After his discharge from the Army, Grell returned to Chicago and worked throughout the United States as a noted muralist and painter. See more works by Louis Grell and learn more about his biography at www.louisgrell.com

To see the illustrations that Grell provided for the Straight Grain, see the gallery below.