Part of a series of articles titled Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Authors of the United States.

Article

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Nathaniel Hawthorne

Dear Sir, The agent of the American Stationers Company will send you a copy of a book entitled ‘Twice-told Tales’ – of which, as a classmate, I venture to request your acceptance. We were not, it is true, so well acquainted at college, that I can plead an absolute right to inflict my ‘twice-told’ tediousness upon you; but I often regretted that we were not better known to each other, and have been glad of your success in literature and in more important matters. I know not whether you are aware that I have made a great many idle attempts in the way of Magazine and Annual scribbling. The present volumes contain such articles as seemed best worth offering to the public a second time; and I should like to flatter myself that they would repay you some part of the pleasure which I have derived from your own Outre-Mer.1

Though Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Nathaniel Hawthorne graduated together as members of Bowdoin College’s class of 1825, the friendship between the two men truly started with the above letter, written by Hawthorne to Longfellow on March 7, 1837. Hawthorne had been “scribbling” for periodicals for years, without significant financial success. His friend Horatio Bridge encouraged him to collect some of these short works into book form and secretly subsidized its publication (Bridge did not reveal this secret to Hawthorne until he earned back his investment).2 The book, Twice-Told Tales, included such now famous works as “The Minister’s Black Veil,” “The May-Pole of Merry Mount,” and “Wakefield.” The book was published the day before Hawthorne’s letter to Longfellow (with a cover price of $1).3

Longfellow responded to Hawthorne’s unsolicited gift by writing a 14-page review of the book, which was left unsigned when published in the North American Review’s July 1837 issue.4 He called Hawthorne a rising star and wished success on the book, noting, “It comes from the hand of a man of genius.” Longfellow particularly emphasized the American character of the tales and their beauty (he seemed to ignore the darkness that characterized his work, which Herman Melville would later underscore). Hawthorne noted how much the book was “puffed” (i.e. having positive reviews, often planted at the direction of the book’s author or publisher) and initial sales were good.5 The timing was poor, however, as the Bank Panic of 1837 helped force the American Stationers’ Company out of business.6

Longfellow and Hawthorne had not been friends at Bowdoin College, at least partially because of their respective loyalties to the Peucinian Society and the Athenaeum Society. Further, Longfellow (b. 1807) would have been perceived as quite young compared to Hawthorne (b. 1804). More importantly, however, Longfellow was a much better student than Hawthorne, having finished fourth in the class. Hawthorne was less successful. As he admitted: “I was an idle student, negligent of college rules and the Procrustean details of academic life, rather choosing to nurse my own fancies than to dig into Greek roots and be numbered among the learned Thebans.”7

Despite this lack of significant interaction prior to Hawthorne’s letter, the two men had an immediate connection in 1837. Longfellow admitted he had read some “glimpses” of his former classmate’s published tales, and that “these glimpses have always given me very great delight.”8 This prompted a surprisingly open response from the typically reserved Hawthorne on June 4, 1837:

It gratifies me to find that you have occasionally felt an interest in my situation... For the last ten years, I have not lived, but only dreamed about living... I have nothing but thin air to concoct my stories of, and it is not easy to give a lifelike semblance to such shadowy stuff. Sometimes, through a peep-hole, I have caught a glimpse of the real world; and the two or three articles, in which I have portrayed such glimpses, please me better than others... To be sure, you could not well help flattering me a little; but I value your praise too highly not to have faith in its sincerity.9

Perhaps it was this openness that inspired the friendship to blossom so quickly – and that inspired Longfellow’s extravagant praise in his review of Twice-Told Tales. “There are at least five persons who think you the most sagacious critic on earth,” Hawthorne wrote Longfellow in a thank you letter after the review’s publication, “viz., my mother and two sisters, my old maiden aunt, and finally, – the sturdiest believer of the whole five, – my own self.”10 Hawthorne mentioned in the same letter the possibility of coming to Cambridge for a talk, though it is unclear if he made the trip (Longfellow may have been transitioning to a new home at the time; he moved to Brattle Street within about two months by August 1837).

The next year, however, shows several indications of both successful and unsuccessful meetings between the two men. In March 1838, for example, Longfellow records visiting Hawthorne at his Herbert Street home in Salem. He was still in bed11 and so Longfellow returned after dinner and “passed the afternoon with him, discussing literary matters. A man of genius and a fine imagination.”12 By the end of that year, they had discussed and possibly began working on a collaborative book project: The Boys’ Wonder Horn, a book specifically for children. Their ambitions were apparently quite lofty, and Hawthorne predicted they might “entirely revolutionize the whole system of juvenile literature.”13 By October 1838, Hawthorne asked his would-be collaborator, “Have you blown your blast; or will it turn out a broken-winded concern? I have not any breath to spare just at present, yet I think it a pity that the echoes should not be awakened far and wide by such an admirable instrument.”14 A few days later, Longfellow reported he was going to visit this “strange owl,” likely to discuss the project.15 The Boys’ Wonder Horn, however, was never completed, apparently after Longfellow asked to work on the project alone. Hawthorne, who did not seem much bothered by the decision, wrote to him by January 1839 about his refusal "to let me blow a blast upon the 'Wonder-Horn.’ Assuredly, you have a right to make all the music on your own instrument,” before jokingly threatening to write a competing work.16 That same month, Hawthorne was granted a political appointment at the Boston custom house – a tedious job that stymied his literary work.

Nevertheless, Hawthorne continued to support the work of his friend Longfellow. “I read your poems over and over, and over again, and continue to read them at all my leisure hours; and they grow upon me at every re-perusal,” Hawthorne wrote.17 Longfellow respected Hawthorne enough that, as he recorded in his journal in January 1840, that Hawthorne was one of only a few gentlemen he gathered at Craigie House to discuss his new ballad, “The Wreck of the Hesperus.” He reported that he would have it printed on a sheet with an illustration and that “Nat. Hawthorne is tickled with the idea.”18

In the meantime, Hawthorne was secretly pursuing a fellow Salem native named Sophia Peabody while Longfellow was being rebuffed by Bostonian Frances “Fanny” Appleton. Hawthorne and Peabody married in July 1842 while Longfellow was on sabbatical in Europe. After Longfellow’s return, Hawthorne teased him for not writing a letter of congratulations on his marriage, “but it does not seem to be forthcoming,” but reassured him that both he and his wife were well.19 In the same letter, he invited Longfellow to speak at the Concord Lyceum for “the magnificent sum of ten dollars.”20 The invitation was declined; neither Longfellow nor Hawthorne would be known as public readers or lecturers. On Christmas Eve, Hawthorne noted the difficulty he had to come for dinner and instead invited his bachelor friend to join him and his wife at their home, The Old Manse in Concord, noting “you will have to warm yourself by the glow of our felicity.”21 Longfellow apparently did not take up the invitation.

By this time, Longfellow had just published Poems on Slavery – to Hawthorne’s surprise. Though he was sure of their “excellence,” he wondered as his friend had “never poeticized a practical subject hitherto.”22 Hawthorne came to Cambridge not long after this on March 21, 1843, and the two writers discussed Hawthorne’s latest short story, “The Birth Mark.”23 Shortly after that visit, Longfellow married Appleton; it was almost exactly a year after the Hawthornes’ wedding. Later, Longfellow and Hawthorne shared space in print in Philadelphia-based Graham’s Magazine, one of the most popular periodicals of the day, in an issue which published both “The Arsenal at Springfield” and “Earth’s Holocaust.”24

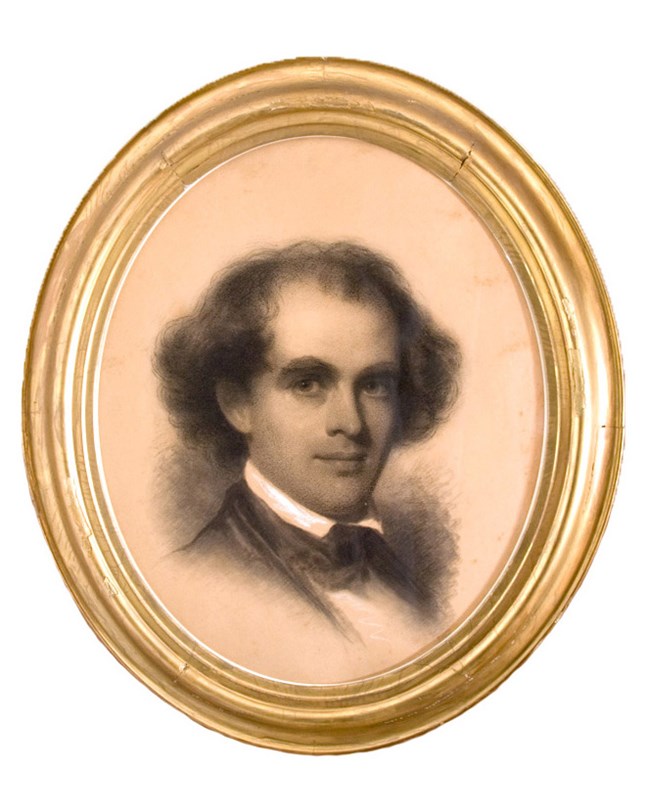

Museum Collection, Longfellow House - Washington's Headquarters NHS (LONG 542)

Shortly after his marriage to Appleton, Longfellow went about decorating his new study. He commissioned an artist named Eastman Johnson (1824-1906) to create crayon and chalk portraits of his family and a few of his close friends at the time: Cornelius Conway Felton, Charles Sumner, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Hawthorne. The resulting 21 x 19” image of Hawthorne is the only known professional drawing of him made during his lifetime.25

Johnson was then just 22 years old and working out of a studio in Amory Hall in Boston. Longfellow urged Emerson to look at the Hawthorne portrait as it was in progress in a letter dated November 24, 1846: “When you are next in Boston, pray take the trouble to step into Johnson’s room and see the portrait he is making of Hawthorne for me.”26 Hawthorne first sat for the portrait on October 14. As he wrote to Longfellow, “My wife is much delighted with the idea –all previous attempts at my ‘lineaments divine’ having resulted unsuccessfully.” Hawthorne himself apparently was less enthusiastic than his wife, joking about one of his upcoming sittings: “I hope he will be otherwise engaged.” The drawing took Johnson longer than normal; it was still incomplete by March 20, 1847.27 Hawthorne’s portrait still hangs in Longfellow's study today.

Fanny Appleton Longfellow made one of the more acute observations of the Salem author not long before the portrait was made, by privately writing that he was “the most shy and silent of men. The freest conversation did not thaw forth more than a monosyllable.”28

In the next few years, the authors visited one another less than either one liked. In one visit, Hawthorne reported back to his wife at the Old Manse, “We had a very pleasant dinner at Longfellow’s; and I liked Mrs. Longlady (as thou naughtily nicknamest her) quite much. The dinner was late; and we sate long.”29 Eventually, Hawthorne moved from Concord to Salem, widening the gap between the two men. Nevertheless, they maintained a somewhat frequent correspondence. Perhaps most notable in the years following their respective marriages is the shared connection in the genesis of Evangeline. A Salem friend named Horace Connelly had been encouraging Hawthorne to write a tale about the Acadians; he refused. Instead, he offered the idea to Longfellow, who then spent several months studying families from Nova Scotia.30 When Evangeline was published, Hawthorne loved the book and wrote to Longfellow, November 11, 1847: “I have read Evangeline with more pleasure than it would be decorous to express. It cannot fail, I think, to prove the most triumphant of all your successes.”31 He also informed him of a review he wrote which would be published two days later in the Salem Advertiser. In it, he noted that “an ordinary writer” would have focused solely on “only gloom and wretchedness” but Longfellow was able to show “its pathos all illuminated with beauty.”32 Longfellow, in turn, thanked his friend for sharing the story: “This success I owe entirely to you, for being willing to forego the pleasure of writing a prose tale, which many people would have taken for poetry, that I might write a poem which many people take for prose.”33 At the same time, Hawthorne confided in Longfellow that his customhouse job was hindering his ability to write: “I am trying to resume my pen, but… my situation … [is] so anti-literary, that I know not whether I shall succeed… I found myself dreaming about stories, as of old; but these forenoons in the Custom House undo all that the afternoons and evenings have done… I should be happier if I could write.”34 Longfellow would echo similar sentiments in his professorship at Harvard: “This college work is like a great hand laid on all the strings of my lyre, stopping their vibrations.”35

Hawthorne continued to enjoy Longfellow’s writing. Kavanagh, for example, he called “a true work of genius, if ever there was one.”36 Longfellow also came to admire Hawthorne’s works. In addition to his positive notice of Twice-Told Tales (he also wrote a second review of the book when it was reissued), he privately noted his appreciation of, for example, The Scarlet Letter and The House of the Seven Gables. “I was a true prophet in predicting your success as a Romance Writer!” he joked in a letter in 1851.37 Longfellow, incidentally, was mentioned, along with Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Bronson Alcott, in the “Custom-House” introductory sketch to The Scarlet Letter: “after becoming imbued with poetic sentiment at Longfellow's hearth-stone; – it was time, at length, that I should exercise other faculties of my nature, and nourish myself with food for which I had hitherto had little appetite [e.g. writing a book].” Longfellow wrote of it, “a most tragic tragedy. Success to the book!”38

The two saw each other slightly less around the time of the publication of Hawthorne’s two famous novels; after leaving Salem, he moved to Lenox in the Berkshires of western Massachusetts, though he dined with the Longfellows one last time before he moved, on April 21, 1850. When he returned, Hawthorne was in need of a new home and Longfellow accompanied him.39 He eventually purchased The Wayside in Concord, former home of the Alcott family, now part of Minute Man National Historical Park.

Not long after, Hawthorne used his literary talents to write a campaign biography in support of his friend and fellow Bowdoin graduate Franklin Pierce, who was running for President. After Pierce’s election, he was rewarded with the lucrative position of Consul to Liverpool. Longfellow hosted a farewell dinner to Hawthorne on June 14, 1853, at Craigie House. Guests included Emerson, James Russell Lowell, Charles Eliot Norton, and the poet’s brother Samuel. “The memory of yesterday sweetens to-day,” Longfellow wrote the next day. “It was a delightful farewell to my old friend. He seems much cheered by the prospect before him, and is very lively and in good spirits.”40

While he was overseas, the two men continued corresponding; Hawthorne even hoped his friend would come to England to visit, especially after Longfellow’s retirement from Harvard in 1854. Hawthorne was particularly impressed that his friend’s fame was even stronger in Europe than in the United States. “No other poet has anything like your vogue,” he assured him.41 In 1855, Longfellow sent a copy of The Song of Hiawatha as soon as it was published. Hawthorne thanked him and reported he read it with “great delight,” even while he admitted he had “no very strong inclination to return, though I sometimes try to flatter myself that I am homesick.”42 After his consulship, Hawthorne traveled with his family through Italy. Publisher James T. Fields joked that he would never come back unless he retrieved him personally – so he traveled to Europe and brought the Hawthornes home. (While with Hawthorne, he reported to Longfellow that their friend had grown a mustache, and lamented that Longfellow had gotten rid of his. No images or other indications of Longfellow having a mustache exist.)

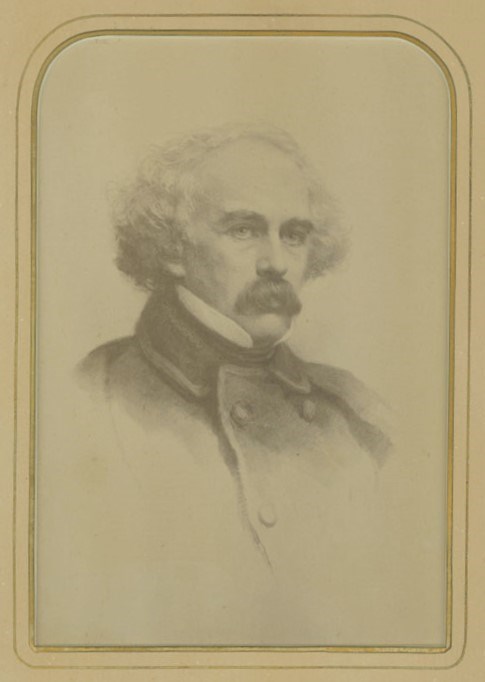

Museum Collection, Longfellow House - Washington's Headquarters NHS (LONG 4365)

Not long after returning, Fields convinced Hawthorne to sit for Boston photographer W. H. Getchell, resulting in at least three photographs. George Parsons Lathrop later referred to one of these poses as “an excellent photograph”; another, Sophia Peabody called “very bad.” The former, with Hawthorne holding his felt hat in hand, was taken December 19, 1861. Hawthorne sent a copy to his friend Horatio Bridge, writing, “I send you, enclosed, a respectable old gentleman who, my friends say, is very like me.” One of those friends may have been Longfellow, who owned a photograph of an engraving of the image, currently hanging on the wall between the study and the library. It may be based on the one that Fields had engraved a year and a half after Hawthorne’s death. The drawing was done by Samuel Rowse (1822-1901) and Hawthorne’s widow Sophia considered the resulting image “a miracle.” Longfellow’s copy of the image, likely based on the Rowse drawing, is seen in a photo of the front hall dating some time before 1877.43 Still, many complained of the difficulty of truly capturing Hawthorne’s image, be it in photography or painted portrait. William Dean Howells referenced Longfellow’s copy of the Getchell image in his book Literary Friends and Acquaintances: “I remember that one night at Longfellow’s table, when one of the guests happened to speak of the photograph of Hawthorne which hung in a corner of the room, [James Russell] Lowell said, after a glance at it, ‘Yes, it’s good; but it hasn’t his fine accipitral look’” – meaning, “hawk-like” (not much different from Longfellow’s view of Hawthorne as a strange owl).44

Back in the United States, Hawthorne used his experiences in Italy as an inspiration for his next book, The Marble Faun. The Longfellows received an advance copy of the new novel; Mrs. Longfellow called it “a rich and fascinating book”45 but her husband said it had “the old, dull pain in it that runs through all Hawthorne’s writings.”46

Longfellow would suffer his own pain in July 1861, after his wife’s tragic death. Hawthorne was unable to write his friend directly and instead asked their mutual publisher James T. Fields, Hawthorne to James Fields after hearing of the death of Fanny Longfellow, July 14, 1861:

How does Longfellow bear this terrible misfortune? How are his own injuries? Do write, and tell me all about him. I cannot at all reconcile this calamity to my sense of fitness. One would think that there ought to have been no deep sorrow in the life of a man like him; and now comes this blackest of shadows, which no sunshine hereafter can penetrate! I shall be afraid ever to meet him again; he cannot again be the man that I have known.47

Longfellow stopped attending meetings of the Saturday Club – a group to which Hawthorne had been elected while overseas, though he seldom attended. In Longfellow’s absence, he wanted to attend even less. As he wrote: “The dinner-table has lost much of its charm since poor Longfellow has ceased to be there, for though he was not brilliant, and never said anything that seemed particularly worth hearing, he was so genial that every guest felt his heart the lighter and the warmer for him."48

Longfellow recovered slowly, even as the Civil War began. Hawthorne, in the meantime, began to age rapidly. Seeing him at the end of February 1863, Longfellow noted, “He looks gray and grand, with something very pathetic about him.”49 About a week later, Hawthorne offered a reciprocal description of his aging friend: “[His] hair and beard have grown almost entirely white, and he looks more picturesque and more like a poet than in his happy and untroubled days. There is a severe and stern expression in his eyes, by which you perceive that his sorrow has thrust him aside from mankind and keeps him aloof from sympathy.”50

Hawthorne died May 19, 1864, at the age of 59. Longfellow served as a pallbearer, along with Oliver Wendell Holmes and James T. Fields, among others. “And Hawthorne, too, is gone!” Longfellow wrote on the day of the funeral. “I am waiting for the carriage which is to take Greene, Agassiz, and myself to Concord this bright spring morning, to his funeral. Do not be disheartened,” he encouraged his friend Senator Charles Sumner, “You have much work of the noble kind to do yet. Let us die standing… I am full of faith, hope, and good heart.”51

After the funeral, Longfellow wrote a moving poem, originally published as “May 23, 1864” (the date of the funeral), now known as “Hawthorne.” The poem accurately describes the day as the “one bright day” after “the long week of rain,” and the various scenes of Concord from that day. He also alludes to “the tale half told,” a reference to The Dolliver Romance, Hawthorne’s last novel, which never developed beyond the second chapter. The poet admitted he felt the lines were “imperfect and inadequate.” Their mutual friend Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote a longer biographical treatment of Hawthorne for the same issue of the Atlantic Monthly that published Longfellow’s poem.

Longfellow continued corresponding with Hawthorne’s widow, Sophia Peabody Hawthorne. She had given him a copy of Oliver Goldsmith’s writings which had previously belonged to her husband. “I hardly need tell you how much I value your gift,” he wrote, “and how often I shall look at the familiar name on the blank leaf – a name which more than any other links me to my youth.” In the same letter, he strongly implied that he had never visited The Wayside before. Hawthorne took advantage of Longfellow’s experience in publishing to ask advice on whether or not she should publish some of his private papers and journals. After speaking with Longfellow (and others, including George Hillard) she wrote to publisher James T. Fields, “After the most careful consideration and consultation… I am convinced that Mr. Hawthorne would never have wished such an intimate domestic history to be made public, and I am astonished at myself that I ever thought of doing it.”52

Years later, Longfellow sent a copy of his translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy to Hawthorne, who had loved her time in Italy. She praised Longfellow’s translation and noted, “I am sure you have not a friend in the world who could more value this book.”53 She died in 1871. After Longfellow’s death, Hawthorne’s son Julian Hawthorne wrote two biographies of his father, which offered additional information and insight into the friendship of the two men.

Notes

- Samuel Longfellow, ed., Life of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1886), Volume I, 260.

- See James R. Mellow, Nathaniel Hawthorne In His Times (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1980), 78.

- See Brenda Wineapple, Hawthorne: A Life (New York: Random House, 2004), 92.

- See Philip McFarland, Hawthorne in Concord (New York: Grove Press, 2004), 58–59.

- See Samuel A. Schreiner, Jr., The Concord Quartet: Alcott, Emerson, Hawthorne, Thoreau, and the Friendship that Freed the American Mind (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, 2006), 120.

- See Wineapple, Hawthorne, 93.

- Edwin Haviland Miller, Salem Is My Dwelling Place: A Life of Nathaniel Hawthorne (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1991), 76.

- Wineapple, Hawthorne, 93.

- Wineapple, Hawthorne, 96; additional quotes from Longfellow, Life, vol. I, 264-265.

- Longfellow, Life, vol. I, 265-266.

- See Mellow, Hawthorne, 112-113.

- Longfellow, Life, vol. I, 292-293.

- Sarah Wadsworth, In the Company of Books: Literature and Its "Classes" in Nineteenth-century America (Liverpool University Press, 2006), 210.

- Longfellow, Life, vol. I, 309.

- Quoted in Robert L. Gale, A Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Companion (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2003), 104.

- Wadsworth, In the Company of Books, 210.

- Longfellow, Life, vol. I, 349.

- Longfellow, Life, vol. I, 353-354.

- November 1842. McFarland, Hawthorne, 61.

- Mellow, Hawthorne, 222.

- Longfellow, Life, vol. I, 450.

- Mellow, Hawthorne, 222-223.

- See Mellow, Hawthorne, 223. Note that Longfellow addressed the letter “Dearest Hawthornius,” and the nickname implies a more than casual intimacy.

- March 1844. See Edward Wagenknecht, ed. Mrs. Longfellow: Selected Journals and Letters of Fanny Appleton Longfellow (New York: Longmans, Green and Co., 1956), 110.

- This statement ignores the “amateur” sketches later done by his wife Sophia Peabody.

- Andrew Hilen, ed., The Letters of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1972), Volume 3, 124.

- For much of this information, see Rita K. Gollin, Portraits of Nathaniel Hawthorne: An Iconography (Dekalb, Ill: Northern Illinois University Press, 1983), 23-24.

- May 25, 1844. See Wagenknecht, Mrs. Longfellow, 112.

- Quoted in P. McFarland, Hawthorne in Concord, 100.

- See Randy F. Nelson, The Almanac of American Letters (Los Altos, California: William Kaufmann, Inc., 1981), 182.

- Gale, Longfellow Companion, 104.

- Ron McFarland, The Long Life of Evangeline: A History of the Longfellow Poem in Print, in Adaptation and in Popular Culture (McFarland, 2010), 45.

- Letter, Henry W. Longfellow to Nathaniel Hawthorne, November 29, 1847, quoted in Andrew Hilen, ed., The Letters of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1972), Volume 3, 146.

- Miller, Salem, 265.

- Journal, Henry W. Longfellow, November 21, 1850.

- Letter, Nathaniel Hawthorne to Henry W. Longfellow, June 5, 1849. Richard Kopley, The Threads of The Scarlet Letter: A Study of Hawthorne’s Transformative Art (Cranbury, NJ: Rosemont Publishing, 2003), 138.

- Letter, Henry W. Longfellow to Nathaniel Hawthorne, August 8, 1851, quoted in Andrew Hilen, ed., The Letters of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1972), Volume 3, 306.

- Journal, Henry W. Longfellow, March 16, 1850, quoted in Longfellow, Life, vol. II, 162.

- Journal, Henry W. Longfellow, February 10, 1852, quoted in Longfellow, Life , vol. II, 217.

- Journal, Henry W. Longfellow, June 15, 1853, quoted in Longfellow, Life, vol. II, 234.

- Letter, Nathaniel Hawthorne to Henry W. Longfellow, May 11, 1855, quoted in Longfellow, Life, vol. II, 258.

- Letter, Nathaniel Hawthorne to Henry W. Longfellow, November 22, 1855, quoted in Longfellow, Life, vol. II, 263-264.

- For much of this information, see Gollin, An Iconography, 79-84.

- William Dean Howells, Literary Friends and Acquaintance (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1900), 51-52.

- Letter, Fanny Longfellow to Emmeline A. Wadsworth, March 6, 1860, in the Frances Elizabeth Appleton Longfellow (1817-1861) Papers, 1825-1961 (LONG 20257), Longfellow House-Washington’s Headquarters NHS.

- Journal, Henry W. Longfellow, March 1, 1860, quoted in Longfellow, Life, vol. II, 351.

- Letter, Nathaniel Hawthorne to James T. Fields, July 14, 1861, quoted in P. McFarland, Hawthorne in Concord, 244.

- P. McFarland, Hawthorne in Concord, 276-277.

- Journal, Henry W. Longfellow, February 28, 1863, quoted in Longfellow, Life, vol. II, 391.

- Letter to Henry Blight, March 8, 1863, quoted in P. McFarland, Hawthorne in Concord, 277.

- Longfellow, Life, vol. II: 407.

- Letter, Sophia Peabody Hawthorne to James T. Fields, January 30, 1868. Nicholas R. Lawrence & Marta L. Werner, eds., Ordinary Mysteries: The Common Journal of Nathaniel and Sophia Hawthorne (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 2005), 325. (emphasis in original)

- Letter, Sophia Peabody Hawthorne to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, November 10, 1867, in the Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Family Papers, Longfellow House-Washington’s Headquarters National Historic Site, Longfellow House-Washington’s Headquarters NHS.

Last updated: March 24, 2023