Last updated: May 1, 2025

Article

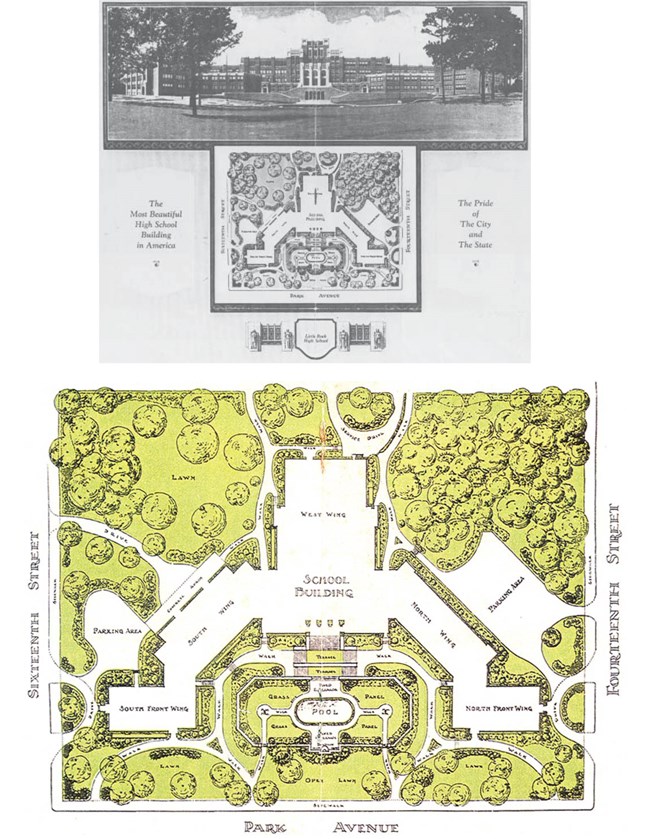

Little Rock Central High School Cultural Landscape

Introduction

On September 25, 1957, public attention focused on nine African American students -- the “Little Rock Nine” -- as they again attempted to attend their first full day at Little Rock Central High School. Federal troops escorted the Little Rock Nine into the school, which was surrounded by a mob of white segregationists. Students Minnijean Brown, Terrence Roberts, Elizabeth Eckford, Ernest Green, Thelma Mothershed, Melba Pattillo, Gloria Ray, Jefferson Thomas, and Carlotta Walls effectively desegregated the historically white high school through their attendance that year. Although Central closed following the conflict over desegregation, it reopened in 1959 and continues to operate today. It is the only operating high school listed as a National Historic Site.

Central High Museum, Inc. / NPS (in Central High School NHS Cultural Landscape Report)

Landscape Description

The site occupies over 28 acres in an urban area of Little Rock, Arkansas, extending to Jones Street to the west, Daisy L. Gatson Bates Drive to the north, 16th Street to the south, and Park Street to the east. It includes Quigley Stadium, playing fields, a playground, parking lots, a sunken plaza, a rear seating plaza, a plaza between the school and the gym, Campus Inn, Tiger field house, Matthews Library, Mobil Gas Station, and two vacant lots on the corners of 14th and Park Streets, as well as the roads and sidewalks surrounding the site.The American Institute of Architects named the Little Rock Central High School “America’s Most Beautiful High School” upon its completion in 1927. The main structure consists of a central portion and four wings, composed of steel framing and bricks. Double stairs lead up to the second floor main entry. At the entry, four Greek muse statues representing Ambition, Personality, Opportunity, and Preparation adorn the façade pilasters. Architects George R. Mann, Eugene John Stern, John Parks Almand, George H. Wittenberg, and Lawson L. Delony designed the structure in Neo-Gothic Revival style. The landscape architect, John Highberger, chose a more minimalist style for the grounds. The non-extant plaza design included a sunken garden, with a reflecting pool and fountain. Curvilinear paths, large oak trees, and evergreen shrubs also define the space. In 2001, a commemorative garden was added on site grounds to honor the Little Rock Nine and the school’s legacy in public education.

Historic Use

Despite the Fourteenth Amendment equal protection clause, suppression of black Americans’ civil liberties continued well into the 20th century. The Supreme Court’s decision in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) sustained black disenfranchisement by upholding the “separate but equal” doctrine. The decision also contributed to the “Jim Crow” laws, most prevalent in the southern states, which extended the separation of facilities to many areas of public life. The landmark case, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954), reversed the Plessy v. Ferguson decision decreeing school segregation unconstitutional. Brown II further promoted integration by mandating that school districts’ desegregation plans should be implemented “with all deliberate speed.” White segregationists, especially in the upper southern and border states, perceived mandatory integration as a federal misuse of power. They employed the interposition doctrine to justify resistance to the decision. The resistance to school integration occurred through a variety of means.The Little Rock school board resisted desegregation by attempting to delay black student admission to Little Rock Central High School until construction ceased on Hall High School. Administrators intended for Hall High School to serve the wealthy white population to the west who previously attended Central. Although school board members opposed integration, they complied with the Federal Constitutional requirements and provided an integration plan that consist of three phases in 1954. Despite the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) claim that the plan could take up to eleven years, which contradicted the “deliberate speed” requirement, the federal courts approved the plan.

Image in NPGallery

Image in NPGallery

As a result of continued resistance to integration and federal authority, Central closed for a year. In June of 1958, community members voted in favor of the Little Rock school board's delay of the integration order, a decision which was denied by the U.S. Supreme Court. Governor Faubus immediately responded by signing 14 bills into law closing all of Little Rock’s high schools. Little Rock moderates and community leaders mobilized to gain support in reopening and desegregating the schools. The moderates fought the segregationists to win a majority in the forced election for the school board seats. In June of 1959, the new members announced the schools would reopen in alignment with the federal courts’ orders. Little Rock public high schools reopened on August 12, 1959.

Left image

Central High School, ca. 1957-1958.

Credit: Central High Museum, Inc., COLL.B.12.I.257, no date, National Park Service, Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site

Right image

Many features from the historic period still exist. However, the utility poles that once lined S. Park Street are gone.

Credit: NPS Central High School Cultural Landscape Report (2007)

Quick Facts

- Cultural Landscape Type: Historic Site

- National Historic Landmark

- National Register Significance Criteria: A, C

- Period of Significance: 1954-1959