New York Public Library

This American Latino Theme Study essay explores how Latinos changed the profile of sports in the U.S. and includes topics such as racial segregation/integration, inclusion, Latina athletes, and community cohesion.

by José M. Alamillo

Beyond the Latino Sports Hero: The Role of Sports in Creating Communities, Networks, and Identities

La Colonia neighborhood in the city of Oxnard, California, is notorious for its crime and street gangs, but it is also known for producing some of the toughest Latino prizefighters in the sport of boxing. In 1978, the Community Service Organization chapter led a city-wide effort to form La Colonia Youth Boxing Club to help steer youth away from gang life and towards sports. Longtime community leader and boxing trainer Louie "Tiny" Patino started the youth program in his backyard and later received financial support from the city to open a boxing gym in La Colonia. City officials saw the potential of helping troubled youth and creating a positive image of the neighborhood. Patino enlisted the help of Eduardo Garcia, a former strawberry farmworker turned boxing trainer, to run the boxing club and keep kids out of trouble.

La Colonia Boxing Gym became a safe refuge for many troubled Latino youth who later became top professional boxers. One of these was 16-year-old Fernando Vargas. An angry kid with no father figure, Vargas was suspended from school and was headed to the mean streets until he stumbled upon the boxing gym. Under the guidance of Garcia, Vargas compiled an extraordinary amateur record of 100 wins and 5 losses and when he turned professional, he became the youngest fighter to win the world light middleweight title. Eduardo Garcia also trained other boxers such as Victor Ortiz, Brandon Ríos, Miguel Angel García, Danny Pérez, and his son Robert García. Because of the training and mentorship of Patino and García, La Colonia Boxing Gym became known as "La Casa de Campeones" (The House of Champions) in boxing circles for producing top-notch fighters with championship belts.[1]

I begin with the story of La Colonia Boxing Gym to show that Latino athletes do not become sports heroes through individual achievement alone. Rather they are supported along the way by a network of community leaders, coaches, family, friends, and fans. Mainstream journalists and scholars have tended to focus more on the professional and individual sports stars overcoming barriers to become ultimately great champions. However, to reduce or simplify the history of Latino sports around individual champions only obscures the historical communities and social networks that helped produce them.[2] I use the term "Latino" when discussing persons, both male and female, who were born and/or raised in the U.S. but originated from Latin America and the Caribbean. Sometimes I will use the term "Latina" to refer specifically to female persons of Latin American descent. I will use "Latin American" to refer to those athletes who migrated from Latin America to the United States to play professional or college sports. Like other cultural practices, sport has involved Latinos who can trace their roots to several generations within the U.S. and those who arrived recently as migrant athletes.[3]

This essay will focus on the Latino sporting experiences in the U.S. from the 19th century up to the present, with emphasis on professional, school-based, and amateur sports. I will highlight specific sports in which Latinos have participated including rodeo, baseball, boxing, football, basketball, soccer, and other sports. Because Latinos encompass considerable diversity across and within different subgroups, it is important to pay attention to the national origins of the players and their communities that provided a supportive network and fan base. The first section will examine the major barriers that kept Latinos from participating in American sports. The second section focuses on Latino participation in rodeo, baseball, boxing, basketball, football, soccer, tennis, golf, and hockey. The final section will explore the history of Latina athletes. While not a new phenomenon, most scholars have overlooked the athletic history of Latinas.

Latinos have made a large impact on American sports since the early 19th century. Like other immigrant groups, sports facilitated the adjustment of Latino immigrants to urban society, introducing them and their children to mainstream American culture while at the same time allowing them to maintain their ethnic identity. Within the context of limited economic opportunities and racial discrimination, sport offered Latinos a refuge and escape from the grim social realities encountered at work and in the community. Thus, the playing field became a key site for Latino and Latina athletes to (re)negotiate issues of race relations, nationalism, and citizenship in order to gain a sense of belonging in a foreign land. Sports has also been a key part of youth culture from little league to high school, teaching young boys and girls how to play and how to behave according to societal gender norms. For young males sports participation became a way to express their masculine identity and for female athletes, because of a long history of exclusion, sports took on greater importance—to be taken seriously and to achieve gender equity.

Major Barriers for Latino Athletes

Latino participation in sports has been shaped by their racial, class, and gender status in the U.S. One major obstacle has been the high financial cost to participate in sports. For many Latino families struggling to makes ends meet, work was the priority for family members, not playing sports. The costs associated with equipment, transportation, training, and miscellaneous fees often discouraged parents from enrolling their kids in organized sports. During the first half of the 20th century, children of Puerto Rican and Mexican parents confronted a segregated public school system with poorly trained teachers, prohibition on speaking Spanish, emphasis on vocational curriculum, and limited opportunities for physical education.[4] Those few individuals who attended high school had more opportunities to play sports, but they still had to overcome negative stereotypes about their academic and physical abilities.

Scholars have shown that intelligence testing of Mexican, African American, and other non-white students during the 1920s resulted in vocational tracking classes and school segregation.[5] Less well known was the athletic ability testing conducted during the same period that enabled teachers and coaches to racialize minority groups as physically inferior and incapable of playing sports.[6] Former basketball coach at University of Michigan, Elmer D. Mitchell, published a series of articles in 1922 entitled "Racial Traits in Athletics" in the American Physical Education Review. Mitchell made "scientific observations" of 15 "races" to rank their athletic ability. The top tier included American, English, Irish, and German athletes that displayed superior physical ability. The middle tier included Scandinavian, "Latin," Dutch, Polish, and "Negro" athletes who showed some potential for athletic competition. The bottom tier included Jewish, Indian, Greek, Asian, and South American athletes that showed inferior athletic traits. Under the "Latin" category, Mitchell concluded, "The Spaniard tends to an indolent disposition. He has less self-control than either the Frenchman or Italian... [and he] is cruel, as is shown in bull fights of Mexico and Spain."[7] The "South American" athlete according to Mitchell "has not the physique, environment, or disposition which makes for the champion athlete...His climate does not induce to vigorous exercise, so that the average Latin American, while a sport lover, prefers the role of a spectator to that of player."[8] Despite their interest in sports, researchers claimed that the "Latin" races possessed inferior physical traits that were supposedly intrinsic to their biological makeup. These articles demonstrated how race science and physical education became intertwined in the nation's educational system with far reaching consequences for Latino participation in sports.

By the 1930s and 1940s, cultural factors came to replace biological factors as the central explanation for poor athletic performance among Latinos. Social reformers during the Progressive era began targeting Latino immigrants and their children to teach them English and change their cultural values through "Americanization" programs.[9] Physical educators, playground supervisors, city recreation officials, and Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA) directors viewed Latinos as culturally deficient requiring athletic training and coaching to learn "good citizenship"[10] These reformers reasoned that with athletic opportunities Mexican youth might potentially develop them into disciplined, healthy, and loyal American citizens. Sociologist Emory Bogardus promoted more "wholesome recreation" for Mexican immigrants to keep them away from saloons, pool halls, and gambling establishments.[11] In the public schools, physical education teachers were encouraged to form sports clubs to teach teamwork and good sportsmanship. One "Mexican school" principal described plans for a "baseball team" because "these young fellows need wholesome activity and are really hungry, with the same hunger of their elders, for the better things in life."[12] While Americanization programs encouraged Latino participation in American sports, they were less successful in their assimilation objectives. Latinos instead used sports to challenge negative stereotypes about their athletic ability and express cultural and national identities of their own choosing.[13] Some athletes used sports to forge transnational ties with their country of origin and maintain their national identity, while some adopted a hyphenated identity that connected them to both worlds, and others chose to assimilate towards an American identity.[14]Despite their achievements on the playing field, the English-language sports media has continued to misunderstand and misrepresent Latino/a athletes. American sports journalists have relied on racial and gender stereotypes when depicting Latino athletes.[15] The language and cultural barriers between Latino athletes and Anglo sportswriters and sportscasters have contributed to negative feelings on both sides. For example, the Puerto Rican baseball player, Roberto Clemente, who struggled with the English language, disliked sportswriters because they repeatedly quoted him phonetically in print, making him look poorly educated and illiterate. Other Latin American baseball players frowned upon sportswriters who "Americanized" their Spanish names.[16] A few Latino athletes complained about the lack of commercial endorsements and television speaking engagements because of a perceived language handicap.[17] Another common stereotype attributed to Latin American baseball players was the "good field, no hit" descriptor that praised their defensive skills but devalued their batting ability.[18] These negative stereotypes in the sports media did not go unchallenged. Some athletes chose to speak only to Spanish language sportswriters. Others used their English language skills to construct their own public image. For example, Mexican American tennis player, Richard "Pancho" Gonzalez used his "bad boy image" to intimidate opponents on the courts and threatened to renounce his U.S. citizenship and play for Mexico if he did not receive better treatment from the print media.[19]

Latino Sport Participation

Rodeo

Latinos have been involved in sports since the arrival of the Spanish explorers to Florida's east coast in 1513. Spanish and Mexican settlers were involved in gambling such as the card game of Monte and cockfighting. As the ranching economy grew in importance so did horse-related sports such as riding and roping contests, and horseracing. Another popular sport was bear and bull fighting until it was banned by the California legislature in 1855 because it was declared a "bloody sport." In latter decades of the 19th century, Anglo newcomers built racetracks for horse races and other equestrian contests.[20]

The one equestrian sport that influenced the North American rodeo was the charrería. The origins of charrería can be traced to the 16th century when Spaniards introduced horses to the New World.[21] Horses were originally intended to work running cattle and managing ranches. Over time, Spanish vaqueros (herdsman) developed an elaborate set of horsemanship skills that grew into organized riding and roping contests. Mexican horsemen, also known as charros, adapted these equestrian contests to develop a unique sport of charrería. The festive style of charro dress combined with a highly ritualized march, coronation of the queen, Mariachi music, and skillful contests made Charrería into Mexico's national sport. Today, Charrería is still practiced on both sides of the border and is considered the forerunner to the North American rodeo.[22]

By the 18th century, the ranching industry developed in the American Southwest and Mexican charros were hired to work in the big ranches alongside Anglo cowboys. Rodeos were held at least once a year on different ranches after the roundup of cattle and counting of the herds. In California, strict laws were passed to govern the operations of rodeos.[23] After the U.S. annexed almost one-half of Mexico's territory in 1848, the Anglo cattle ranching culture expanded to include Mexican charros. They became a significant portion of the work force as well as the main headliners in "rodeo shows" and "cowboy tournaments" throughout the southwest.[24] At the age of 15, San Antonio native Jose Barrera (also known as "Mexican Joe") was already a trick roping star who toured throughout the United State and Europe as part of Pawnee Bill's Wild West Show.[25] The Wild West shows of the 1890s also featured the most famous trick rider and roping artist, Vicente Oropeza, still considered a charro legend in his hometown of Puebla, Mexico. Oropeza won numerous roping contests and, as part of Buffalo Bill's Wild West shows, inspired audiences to take up the sport of rodeo. He continued competing on both sides of the border until his death in 1923. In 1975, he was inducted into the National Cowboy Hall of Fame in Oklahoma City.[26] During the 1920s some differences between rodeo and charrería began to emerge. One of the main difference is that rodeo is an individual sport that places greater emphasis on speed and endurance, while charrería is a team sport with a focus on style, tradition, and ritual.

Baseball

The one sport that Latinos have developed a long tradition of participation and athletic achievement is baseball. Latinos make up the largest minority group in baseball. Although many consider their presence a recent phenomenon, they have been part of baseball since the game's 19th century origins. As Cuban students in the United States traveled back to Cuba they introduced the game to their friends and family. Also, when the U.S. extended its military and commercial presence on the island in the later 19th century, baseball was adopted by Cubans as a way to become modern and to seek independence from Spain.[27] Baseball soon spread to other Latin American countries as U.S. sailors, miners, railroad workers, and missionaries staged exhibition games with local teams.Baseball developed in the U.S. in part because of the important contributions of both U.S.-born Latinos and Latin American players. One of the first Latin Americans to play major league baseball in the U.S. was Esteban Bellán. In 1863, Bellán left his hometown of Havana, Cuba to study at Fordham University in New York City where he learned to play baseball and later joined the Troy Haymakers playing third base until 1872. The Haymakers joined the National Association, which later became the National League and the Haymakers later became the New York Giants. Another early pioneer in major league baseball was Vincent Irwin "Sandy" Nava, who was born in San Francisco in 1850 to Mexican parents. He often hid his ethnic heritage by using the name of "Irwin Sandy" or "Vincent Irwin" but did not hide his great catching ability. After joining the Providence Grays in 1882, he began to promote his "Spanish" heritage for marketing purposes.[28]

Like the influx of immigrants from Latin America into the general population over the past two decades, there has been an increase of Latino players into the major leagues. The percentage of Latino players in the major leagues grew from 13 percent in 1990 to nearly 30 percent in 2006.[29]Now virtually every major league roster includes one player of Latin American descent. Despite the remarkable stories of Latino players escaping poverty to achieve success in the big leagues, they still face challenges learning a new culture and language, as well as learning how to navigate the color line.

Professional baseball has long proclaimed itself the "national pastime" and symbol of the American "melting pot." However, the melting-pot metaphor applied only to children of European immigrants who were encouraged to shed their ethnicity and become American. Baseball reflected American society's racial segregation practices by excluding African Americans from the national pastime until Jackie Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. Latinos occupy a unique place in baseball's racial history, not fully excluded like African Americans and not fully accepted like Euro-Americans; rather they were racially in-between. Before the integration of baseball, there were over fifty light-skinned Latin American players who joined the Major Leagues, mostly from Cuba. Samuel Regalado's Viva Baseball recounts their motives for leaving their country, their encounters with racism and the language barrier, their difficulties with the press, and their "special hunger" to prove their worth on and off the diamond field.[30]

After 1947, the numbers of Latino players more than doubled with the influx of Afro-Latinos during the 1950s and 1960s. Excluded from the white Major Leagues, Afro-Latinos joined the Negro Leagues and Latin American Leagues in large numbers where they were treated with respect and judged according to their athletic skills. As Afro-Latinos entered the Major Leagues, they experienced a double stigma. As Adrian Burgos Jr. shows in Playing America's Game, they became racial pioneers in major league baseball team rosters and, like Jackie Robinson, should be accorded the same recognition for their integration work.[31] While most Americans can identify Roberto Clemente as the first Latino superstar, for his remarkable baseball skills and acts of humanitarianism, very few recall the story of Orestes "Minnie" Miñoso.[32] Considered the "Latino Jackie Robinson," Miñoso became the first Afro-Latino in the major leagues in 1949 and the first to integrate the Chicago White Sox team in 1951 and the first Afro-Latino to appear in an All-Star game. To this day the National Baseball Hall of Fame continues to deny Miñoso the recognition he deserves for paving the way for Latino players to enter the major leagues.

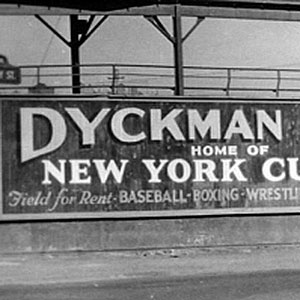

Latino participation in sports was not limited to ballplayers. It also included a network of coaches, managers, owners, and fans. A key figure who encompassed all these roles was Alejandro (Alex) Pompez, an Afro-Cuban who grew up in Havana, Cuba, and Tampa, Florida and later moved to Harlem where he founded the New York Cubans. As the owner of this Negro League team from 1916 to 1950, Pompez used his bilingual/bicultural skills and transnational connections to recruit talented players from the Caribbean and Latin America into the Negro Leagues. In search of a home field, Pompez leased the Dyckman Oval ballpark from the city in 1935 and later installed lights, making it the first professional ballpark in New York with lights. This historic site deserves recognition for being the home of the New York Cubans. After the team folded in 1950 because of declining fan support and the integration of baseball, Pompez became the top Latin American scout for the New York Giants, working tirelessly behind the scenes to ensure that African Americans and Latinos got a fair chance to play for the big leagues.[33] Thirty-four years after his death in 1974, Pompez was finally recognized by Cooperstown when he was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Unable to choose their teams and destinations, Latino professional baseball players were often separated from their communities. Their loneliness was lessened when they joined minor league teams located near Latino neighborhoods where they could find strong fan support and a common language and culture.[34] At the neighborhood level, amateur and semi-pro baseball teams functioned as important community institutions that served multiple purposes. Baseball games on Sunday became a popular form of family entertainment and a means to build a sense of community.[35] For young boys of Mexican immigrants, baseball clubs became a vehicle to express new forms of cultural and masculine identities.[36] Mexican American coaches and players also developed leadership skills and teamwork that became instrumental in political battles for labor and civil rights. [37] The story of Carmelita Chorizeros from East Los Angeles illustrates the strong community ties between baseball, small businesses, sportswriters, and fans. In 1946, the Carmelita Company, which sells pork sausages to local markets, formed a baseball team named "Chorizeros" (Sausage Makers) with local Mexican American residents. The team made their home field at Belvedere Park in East Los Angeles, where they won numerous league championships. Led by its longtime manager Manuel "Shorty" Perez, the Chorizeros became known as the "New York Yankees of East Los Angeles." In 2009, the Latino Baseball History Project and Baseball Reliquary spearheaded a campaign to recognize the Chorizeros and Shorty Perez by dedicating a memorial plaque on the right-field line of the baseball diamond at Belvedere Park.[38]

Football

It is a common assumption that because football demands large and strong bodies, few Latinos have entered the sport. However, since 1929 approximately 96 Latinos have been part of professional football.[39] In the early years of the sport, Latinos were recruited primarily as punters and kickers, but since the 1970s they have played a wide variety of positions. As more Latinos attended colleges and universities with a football scholarship, they began to receive more attention from the National Football League (NFL). The most popular Latino professional football players have included Manny Fernández, Joe Kapp, Tom Flores, Ted Hendricks, Efren Herrera, Anthony Muñoz, Jim Plunkett, Jeff Garcia, Victor Cruz, and Mark Sanchez.

Danny Villanueva was one of the earliest field-goal kickers of Mexican descent in the NFL. Growing up in Tucumcari, New Mexico in a family of twelve, he learned how to kick from playing soccer with his father and the American Youth Soccer Organization. With the support of his family, he played high school football and earned a scholarship to New Mexico State University. After graduation in 1960, he taught high school journalism until he received a phone call to a tryout with the Los Angeles Rams. He earned the top field kicker spot and spent five years with Los Angeles Rams. He broke the single season record for punt average of 45.5 and later helped the Dallas Cowboys reach their first playoffs. After establishing team and league kicking records, Villanueva retired from football at the age of 29 to become a television executive. As the founder of Telemundo and Univision Spanish-language television networks, Villanueva used his NFL experience as a platform to become a successful businessman and a multi-millionaire. According to Villanueva, being in high-pressure situations when kicking field goals helped him maintain focus and calm that allowed him to do bigger things outside of football.[40] In 1991, he established a scholarship for Latino students at his alma mater.

The history of Latino football is not limited to individual NFL stars, but includes the collective efforts of teammates, coaches, and fans. The case of the Donna High School football team that won the Texas championship exemplifies the importance of sports to the local community. Located in the Rio Grande valley of south Texas, Donna was a racially divided town, but Mexican Americans and whites came together to support their high school football team. Coached by Earl Scott and Benny La Prade, the squad was comprised of ten Mexican Americans and eight white players. They were considered the underdogs against a top-ranked team from north central Texas. They pulled an upset by winning the 1961 state title. For the Mexican American players who worked as migrant workers alongside their parents, this victory showed "what [Mexicans] could do, if given an opportunity."[41] Mexican Americans took great pride in their victory that they made a religious pilgrimage to a Catholic shrine in their honor. Historian Jorge Iber found that football helped Donna players develop a strong self-confidence that allowed them to graduate and pursue a college degree and ultimately become middle class professionals.[42] The 1961 victory is still remembered during annual reunions held at the Donna High School stadium, which was named after Coach La Prade.

Soccer

In a recent survey, Major League Soccer (MLS) surpassed the National Hockey League and National Basketball Association as the third most attended professional sport in the U.S. on a per-game basis. In 2012, MLS entered its 17th season with 78 players who were born in Latin American on its 19-team roster.[43] The influx of Latin American players means that more Latino fans will likely pack soccer stadiums. The world's most popular sport, also known as fútbol to Spanish speakers, has established a foothold in the U.S. in part because of a growing Latino population and MLS marketing efforts. Hoping to boost attendance among Los Angeles's Mexican American population, for example, MLS added a new franchise team in 2005 called "Club Deportivo Chivas USA." Like its parent team in Guadalajara, Mexico, Chivas USA is owned by Mexican millionaire Jorge Vergara who founded this team because MLS was missing the "passion" of fútbol. MLS's attempt to market Chivas USA to Latino fans was limited, however, due to the league's restriction on the numbers of international players per team.[44]

Before MLS, Latino soccer players were part of the North American Soccer League (NASL) from the 1970s until the early 1980s. The NASL team rosters were dominated by foreign players including Pelé. This great Brazilian forward played for the New York Cosmos from 1975 to 1977and is considered the best soccer player in the history of the sport. There were 30 Latin American players in the NASL in the early 1970s, but that number declined by half in the late 1970s. The Los Angeles Aztecs (1974-1981) used their Pre-Columbian name to appeal to the Mexican population in the Los Angeles area. This strategy failed because there were no Latino players in their team roster. Public perception of soccer as a foreign sport haunted NASL team owners who worried about declining gate receipts, so they began to "Americanize" the sport by instituting a new rule requiring teams to have native-born players on the soccer field at all times. In response, soccer coach and sportswriter, Horacio "Ric" Fonseca accused the NASL of discriminating against Latinos, both U.S. born and foreign players. He cited examples of three Latino players on the "old" Aztecs who were either traded or released because "they would not sufficiently 'Americanize' soccer—as if U.S. Latinos were not American." [45]

For U.S. Latino communities, fútbol has constituted a source of cultural pride and a way to stay connected to their homeland.[46] With cable or satellite television channels broadcasting soccer matches around the world, fans can cheer for their favorite league or national team. Others can remain connected to their homeland by joining an adult soccer league. More than weekend diversions, soccer leagues resemble multi-purpose social clubs that have helped Latino immigrants adjust to American society, serving as a forum for communication for employment and housing information.[47] These soccer networks have strengthened family and kinship ties and integrated new immigrants into the local community. As immigrants have settled in the U.S., they have organized competitive soccer leagues in order to secure playing fields and find sponsors for team jerseys. Latino soccer clubs in the Washington D.C. area have offered companionship and hometown nostalgia for immigrants who have made the soccer fields into "cultural spaces."[48] The Latino soccer leagues of Chicago and Detroit have also organized and maintained community organizations providing language classes, entertainment, and other social services to its members.[49]

Unlike other sports that rely on a high school and college pipeline, soccer has relied primarily on a youth club system for its growth and development. Youth club soccer has long been the domain of suburban white middle and upper-middle class communities in which poor minority groups have been left outside the soccer pipeline.[50] A majority of working class Latino players cannot afford the high costs of club soccer with its coaches' salaries and travel costs. Instead many Latinos remain playing for local community leagues and high schools.In her study of Richmond High School's soccer team, Ilann Messeri found that playing soccer was more affordable for Latino students because schools, local businesses, and others in the community supported the team financially. Latino parents also supported teams with fundraisers, cleaning the field, and working security during games.[51] Messeri argued that unlike exclusive elite club soccer teams, Richmond High School's soccer team became an important cultural space for Richmond's Latino community.

Not all high schools have been willing to fund a soccer program, however. In A Home on the Field, Paul Caudros wrote about his efforts to help Latino students, many of whom were undocumented, form a high school soccer team. He encountered resistance from school officials and football coaches at the North Carolina high school. One main obstacle was that Latino parents lacked medical health insurance and often worked for low wages in poultry-processing plants, leaving them with few resources to support their kids' athletics. But they managed nonetheless. The team endured racist incidents and hostile fans for three seasons. After the team won the state championship title, they gained more respect from school officials and community residents.[52]

Boxing

Boxing is one of the most popular sports among U.S. born and foreign Latinos. One of the first Latino superstar of the prize ring was Aurelio Herrera. Despite encounters with law enforcement and being denied entry inside San Francisco's rings, Herrera was a hard-hitting puncher from 1898 to 1909, he fought 94 professional bouts winning 64 (57 were knock-outs) and losing 14. Herrera was arrested several times for vagrancy, spent time in jail and died as a homeless alcoholic. [53] After Herrera, a long list of Mexican-descent prizefighters emerged in southern California prize rings throughout the 20th century.[54]

Before Oscar De La Hoya was coined "Golden Boy" there was another prizefighter who owned that nickname. Art Aragon was a popular boxer during the 1950s, which not only had superior boxing skills but also was a charismatic movie star who earned a reputation as a ladies' man. Born in New Mexico and raised in East Los Angeles, Aragon began boxing in 1944 as a lightweight winning a draw at the Olympic Auditorium. In 1950, Aragon gained the respect of the boxing world when he knocked out Enrique Bolanos, a top-rated Mexican light-weight fighter. According to boxing historian Gregory Rodriguez, Aragon was part of the Mexican American generation who sought inclusion in America's public institutions and was a favorite among Hollywood celebrities and English language sports writers.[55]

Since the 1950s, the sport has been a "black-and-brown affair," with Latinos generally controlling the lighter weight categories and African American boxers wining the middleweight and heavy weight divisions. However, with the decline of African American heavyweights in the U.S., attention has shifted toward the West Coast region and lightweight divisions where Latino boxers dominate. Another reason for the "Latinization of boxing" phenomenon is the rise of boxing promoters, like Oscar de la Hoya, who now runs the business and marketing side of boxing.[56]

Latinos have turned to boxing as a way to fight their way out of poverty. They cheered their favorite prizefighter as a way to remember their homeland. Puerto Rico, Mexico, Cuba, and many other Latin American countries have produced the largest number of the world's boxing champions, each one expressing national pride and a distinct fighting style. Puerto Rico has produced over 40 world championship boxers in different weight divisions and 6 Olympic medals. Puerto Rico's first boxing champion was Sixto Escobar who won the bantamweight division title in 1934. Since then, Puerto Rico has produced top champion boxers such as Wilfredo Benitez, Wilfredo Gomez, Hector Camacho, Felix Trinidad, John Ruiz, and Miguel Cotto. Puerto Rican boxing, according to Frances Negrón-Muntaner, "takes on a special value in the fight for the nation's worth and offers both popular and elite sectors a way to narrate, enjoy, and perform nationhood."[57] Puerto Ricans are drawn to the sport of boxing as means to express their nationalistic pride in a world stage.

Puerto Ricans raised in the mainland U.S. have also embraced the Puerto Rican flag inside and outside the ring. Two examples include Carlos Ortíz and Jose "Chegui" Torres. Ortíz was a three-time world champion, twice in the lightweight division, and one in the junior welterweight division. Torres won numerous amateur matches and the light heavyweight champion title in 1965. After retiring Torres became the New York Boxing Commissioner as well as a journalist and political activist in New York City.[58]

Since the early 1920s, boxing has been one of the most popular sports in Mexico. Highly publicized visits by Jack Johnson and Jack Dempsey to Mexico City helped stir more interest in boxing with sold out attendances at boxing rings. Mexican fighters have developed a reputation as rugged, aggressive, passionate, and hard-hitting punchers who fight until the end. Some exceptional fighters include Marco Antonio Barrera, Rubén Olivares, Salvador Sánchez, Vicente Saldivar, and Julio César Chávez.[59] As Mexicans emigrated northward and settled in U.S. cities, communities developed their own prizefighters in backyard arenas and neighborhood boxing gyms. Since many originated from different states of Mexico where regional ties remained strong, it was in the boxing arenas in the U.S. where some felt closer to a Mexican national identity.[60]

Since Mexican migrants faced racial discrimination at work and school they became more conscious of "being Mexican." The arena provided a space for them to achieve a dignity denied to many low-wage Latinos. According to Gregory Rodriguez, boxing was not associated with Americanization, but "came to be identified with 'Mexicanness', with Mexican guts, Mexican spirit, and with Mexican victories."[61] Some of the most famous Mexican American boxers in Los Angeles included Solly Smith, Aurelio Herrera, Joe Rivers, Joe Salas, Bert Colima, Manuel Ortiz, Art Aragon, Juan Zurita, and Mando Ramos.[62]

Beyond individual prizefighters, boxing includes a network of boxing gyms, trainers, promoters, and fans. Latino boxers transformed vacant lots, backyards, garages, abandoned buildings, and small halls into arenas where they staged fights. The best prizefighters were recruited by promoters to fight in the bigger venues for more prize money. The most popular boxing arenas in Los Angeles included the Ocean Park Arena, Main Street Athletic Club, Hollywood Legion Stadium, and the Olympic Auditorium.[63] Built for the 1932 Olympic Games, the Olympic Auditorium staged fights that featured the biggest names in the sport's history. The success of the Olympic, according to longtime owner Aileen Eaton, "has been largely on attracting the Mexican-American fight fan...which makes up about 60 percent of our audience."[64] Boxing promoters understood that to attract bigger audiences they needed to use a fighter's national identity to stir up emotions. Former boxers have also founded gyms in poor ethnic neighborhoods to provide more recreational opportunities for kids and spur economic development. A recent example is Oscar de La Hoya, who returned to his working class neighborhood in East Los Angeles to renovate the gym where he trained as a child and renamed it the Oscar De La Hoya Youth Boxing Center. He also formed Golden Boy Partners in 2005 with a $100 million investment to revitalize his Latino neighborhood.[65]

Basketball

Although Latinos have been playing basketball since the early 1900s, it was only in the 1970s that they entered in the National Basketball Association (NBA). By the 2009-2010 season, there were six U.S- born Latinos players in the NBA and nineteen players from Spain and Latin America. These included Mark Aguirre, Rolando Blackman, Eduardo Nájera, Emmanuel "Manu" Ginobili, Paul Gasol, Carmelo Anthony, and Carlos Arroyo. Ginobili, who grew up in Argentina, and Gasol, who is from Spain, represent two basketball stars who have had remarkable success in European and American basketball leagues. In recent years, 15 percent of NBA fans identified as Latino, thus the NBA has begun to recognize the Latino fan presence and the potential to market the sport to Latino audiences.[66]

Puerto Rico has produced the majority of Latino players in the NBA, including Alfred "Butch" Lee, considered the first Latino to join the NBA. Puerto Rico's national basketball team has also enjoyed success in the Olympic Games. Puerto Rico's victory over the U.S. Olympic basketball team in the first round of the 2004 Olympics surprised many and stirred national pride on and off the island. Puerto Ricans competed successfully against the U.S. Olympic basketball team in part because of their highly competitive professional basketball league.[67] One of the best players in the island's basketball league during the 1950s and 1960s was Juan "Pachín" Vicéns. Born in 1934 in Ciales, Puerto Rico, Vicéns was only 16 years of age when he joined the Ponce Lions of the National Superior Basketball League. His excellent point guard skills helped the Lions win their first championship. Two years later, he won another championship and was declared the Most Valuable Player. In 1954, he was recruited by coach Tex Winter (mentor of Lakers coach Phil Jackson) to Marquette University and later to Kansas State University where he became the second-leading scorer in 1956 (averaging 12.3 points) and led the team to the NCAA Sweet Sixteen. Recruited to play professional basketball in the U.S., he decided to play for the Ponce Lions and the Puerto Rican basketball team. After he retired in 1966, Vicéns became a bank manager and sports radio commentator. In 1972, a statue was dedicated in his honor in front of the Juan Pachín Vicéns Auditorium.[68] This well-known sports venue is located between Victoria 7845 and 68 de Humacao in the city of Ponce, Puerto Rico.

Basketball in Mexican American communities shaped a sense of community and provided a means of interaction with other ethnic communities. In South Chicago, Mexican youth traveled with their basketball teams to compete around the city in the 1930s and 1940s, becoming more aware of how their ethnic identities were perceived by other neighborhood players.[69] In the mining town of Miami, Arizona, Mexican American high school basketball players surprised everyone when they won the 1951 Arizona basketball championship. [70] Led by a Finnish American coach, Mexican American players achieved more than "court success," they helped to develop a sense of ethnic pride, helped to bridge racial divisions in the mining community, and earn a chance to attend college on a scholarship.

In El Paso's Segundo Barrio, basketball was the favorite sport among Mexican Americans. The 2008 documentary Basketball in the Barrio chronicles the remarkable athletic career of Rocky Galarza, a local sports star who founded a unique basketball camp for Latino youth in El Segundo Barrio.[71] El Segundo Barrio is one of the oldest Mexican American neighborhoods in El Paso and according to Gil Miranda it was also the main place where "Hispanic kids grew up playing basketball." Galarza grew up during the 1940s becoming a star athlete at El Paso High School in baseball, football, and basketball. He was also a Texas Golden Gloves champion boxer. He later built a boxing gym behind his sports bar restaurant, becoming a prominent youth sports advocate, boxer trainer, and businessman.[72]

Other Sports

Latinos have also made their mark on other sports such as golf, tennis, horseracing, hockey, and Olympic Games. Both golf and tennis have being associated with rich white country clubs, but this did not stop Latinos from playing and making an impact on these elite sports. The only way that Latinos gained entry into the sport of golf was to become a caddy. This is how the two most well-known Latino golfers got their start. Mexican American golfer Lee Trevino and Puerto Rican golfer Juan "Chi Chi" Rodriguez learned the game by caddying and jumping fences to play golf. [73] In 1978, Nancy Lopez was the first Latina to become a professional golfer. Lopez went on to a remarkable career in the Ladies Professional Golf Association (LPGA) tour, becoming one of the best all-time women golfers and inspiring young Latinas to play the sport.[74] Mexico native Lorena Ochoa and Mexican American Lizette Salas represent a new generation of Latina golfers who are making an impact on the LPGA tour.

Less well known is the story of five Mexican American golfers from San Felipe High School who won the 1957 Texas State High School Golf Championship.[75] These kids learned the game as caddies at a South Texas country club that barred them from playing, so they built their own makeshift golf course in an empty sandlot. Once they formed an official high school team, they found a practice area, better equipment, and good coaching. These young kids began to compete and win against other high school golf teams across the state. They encountered problems entering golf tournaments but it was their strong determination and excellent swings on the green that made them state champions.

As more tennis courts became accessible through public parks and high schools during the 1940s, Latinos began playing and winning tennis tournaments. The first Latino tennis star Richard "Pancho" González grew up playing in the public tennis courts of Exposition Park in south Los Angeles. Growing up in a working-class Mexican American family, González had no formal tennis lessons but he was a natural athlete, winning several junior tournament titles and back-to-back U.S singles titles at Forest Hills in 1948 and 1949. Gonzalez dominated the field of professional tennis when he won 91 singles titles, earning the world' number one ranking for eight years during the 1950s.[76] U.S. and foreign-born Latinas have also made their mark on the tennis world beginning with Brazilian tennis player, Maria Bueno who won 19 Grand Slam titles between 1954 and 1968. Another Latina tennis star was Rosemary "Rosie" Casal, who was born in El Salvador, but grew up in San Francisco where her uncle taught her to play. Despite her short size (5'2"), she dominated women's doubles play with her aggressive and inventive playing style. Puerto Rican Beatriz "Gigi" Fernández was another great women's doubles player during the 1990s. She teamed up with Dominican born Mary Joe Fernandez to win two gold medals for the U.S. at the 1992 and 1996 Olympic Games.[77]

Although there are many tennis stars from Spain and Latin America there are currently no U.S. born Latino players in the men's and women's professional tours. One way to address this problem is to organize Latino tennis tournaments. The first annual La Raza Tennis Tournament was held on June 19, 1976 in San Diego, California. Organized by the La Raza Tennis Association (LRTA) whose purpose was to "foster and develop the game of tennis in San Diego County, to encourage development and participation of promising young players of the Spanish-Speaking community."[78] LRTA was formed to "expand the interest and enjoyment in the game of tennis among the Chicano community and help develop the young tennis talent." One young Chicano who caught the attention of local tennis officials was Angel Lopez, who won the first La Raza Tennis Tournament. As the head tennis instructor at the San Diego Tennis and Racquet Club, Lopez still carries out the mission of the LRTA by donating racquets and teaching tennis to Latino youth in San Diego public schools.

Compared to other mainstream American sports, there have been fewer Latinos in the history of the National Hockey League. Each hockey player comes from vastly different places, teams, and experiences that reflect the diversity of the Latino population. The first was Bill Guerin, who is of Nicaraguan and Irish descent, who joined the Edmonton Oilers in 1998. A year later Scott Gomez, born in Alaska to a Mexican father and Colombian mother, arrived in the league joining the New Jersey Devils and because of his appearance and last name was marked as the "first Latino in hockey," even though he could not speak Spanish. Then there is Raffi Torres, born in Canada of Mexican and Peruvian parents, who joined the New York Islanders but because of his red hair and light eyes few did not consider him Latino.[79]

In horse racing there was a relative advantage for Latino jockeys who were short and lightweight. Puerto Rican Angel Cordero Jr. is considered the leading thoroughbred horse racing jockeys of all time, winning six Triple Crown races during the 1960s and 1970s and ranking third in all-time career wins in racing history. In 1988, he was inducted into the National Museum of Racing's Hall of Fame.[80]

Latina Athletes Breaking Borders

Unlike their male counterparts who look up to Latino sports heroes, Latinas have had few athletic role models and have encountered gender barriers in American sports. Latinas have faced reluctant parents who expected them to help with childcare after school whereas their brothers enjoyed more freedom playing sports. In addition, the concept of "after-school sports" has been a new concept to many immigrant parents arriving from poor Latin American countries. When school officials and coaches made the effort to teach parents about the long-term academic and health benefits of after-school sports for girls, families have often accommodated to their daughters' athletic interests. These benefits were confirmed by a 1989 Women's Sports Foundation research study that found that Latina athletes were more likely to enroll and stay in college.[81]

Even though colleges and universities began to comply with Title IX in 1978 to create gender equity in sport, Latinas have remained underrepresented in collegiate sports.[82] Collegiate softball has been one sport in which Latinas have been more visible.[83] In her study, Kathy Jamieson found that by crossing familial, educational, and athletic borders Latina softball athletes occupied a "middle space" that allowed them to resist easy classification of their multiple identities.[84] The sport's popularity among Latinas can be attributed to the remarkable achievements of Lisa Fernandez, who is considered one of the greatest players in softball history. Born in 1971 in New York City to a Cuban father and Puerto Rican mother, Fernandez began playing softball at an early age and during high school in Lakewood, California. After graduation, she enrolled at University of California Los Angeles where she led the Bruins softball team to two national championships. She also led the USA softball team to win three gold medals in the 1996, 2000, and 2004 Olympic Games. Her stellar pitching and hitting at the Olympic Games helped promote women's softball around the world. In 2001, the Lakewood City Council recognized Fernandez's athletic achievements by naming the softball field at Mayfair Park in her honor.[85]

Beyond softball, Latina athletes have also participated in baseball, basketball, tennis, golf, soccer and boxing. Latina participation in baseball dates back to the 1930s and 1940s when the All American Girls Professional Baseball League (AAGPBL) began recruiting Latinas, especially from the Cuban women's league.[86] One of these players was Isabel Alvarez, who began playing with the Estrellas Cubanas until she joined the AAGPBL in 1948 at age 15. Alvarez was the youngest player and one of seven Cuban women who joined the AAGPBL. After pitching for the Chicago Colleens, she moved around with several teams until settling with the Fort Wayne Daises. Isabel had difficulty learning the English language, but the presence and companionship of other Cuban teammates eased her loneliness and homesickness.[87]

Latinas have been playing basketball since the 1930s. However it was not until 1997 that Rebecca Lobo became the first Latina basketball star. Lobo played for the Women's National Basketball Association (WNBA)until 2003 when she became a television basketball analyst. During the early 1930s, San Antonio's Liga Femenino Hispano-Americana de Basketball was made up entirely of Mexican American women who played on teams with names like "What Next," "Modern Maids," "Orquídea," "LULAC," and "Tuesday Night."[88] These teams were sponsored by mutual-aid societies, fraternal lodges, and voluntary associations from San Antonio's Mexican community. To raise funds for uniforms and travel expenses, basketball teams held dances at the Westside Recreation Center or at Sidney Lanier High School. Playing for the Modern Maids team, Emma Tenayuca was a brilliant student at Main High School and a "sensational" athlete who was selected to San Antonio's All-City girls' basketball team in San Antonio.[89] After her high school graduation, Tenayuca became a labor organizer during the peak of the Great Depression leading the Pecan Sheller workers to major strike in 1938.[90] Basketball taught her invaluable leadership and teamwork skills that were crucial for organizing workers and battling employers and city officials.

Latinas have also been part of the growth of women's soccer in the U.S. When Mexico was unable to produce enough players for their national team they recruited Mexican American players from the U.S.[91] One of these players was Monica Gerardo, daughter of a Mexican father and Spanish mother, who joined the Mexico's 1999 World Cup Team and helped Mexico qualify for its first-ever women's World Cup. Gerardo is one of many U.S. born Latinas who overcame gender barriers in their family and community to play collegiate soccer.[92] When Brazilian soccer star Marta Vieira da Silva, considered the best female players in world, decided to play for the Los Angeles Sol team, young Latinas were lining up to watch her play in the new Women's Professional Soccer league.[93]

While boxing has long been considered a "manly" sport, women have recently entered the sport due in part to the popularity of Hollywood films like the Oscar-winning Million Dollar Baby (2004) and Girlfight (2000). Several working-class Latina boxers photographed and profiled in Women Boxers: The New Warriors revealed the different racial, class, and gender barriers they faced entering the boxing ring. Some photographs show these women in extreme physical training and others show them as loving mothers embracing their children. These photos reveal how these women are constructing new notions of femininity. A few Latinas testified about how they were introduced to boxing by their fathers and brothers. This shows how boxing has long been a Latino family tradition. The question remains whether female boxing will be more than a sexualized spectacle for male spectators and be taken more seriously by those who control the sport, mainly male boxing promoters and media officials.[94]

After the International Olympic Committee allowed women's boxing for the 2012 Olympic Games in London, CNN anchor Soledad O'Brien profiled Mexican American fighter Marlen Esparza as she trained for a spot on the U.S. Olympic team. With the support of her father and coach, Esparza earned a spot on the Olympic team. Outside of boxing Esparza is a pre-med college student at Rice University in Houston, Texas. She has made gre at sacrifices to train for a sport with little financial backing. Her strong determination and dedication paid off recently when she won a bronze medal in the 2012 Olympic Games in London.

Conclusion

In 2003, Latinos surpassed African Americans as the largest minority group in the U.S. Given the obvious importance of athletics in American life and the increasing Latino population in the U.S., it is important to understand the historical and contemporary role of Latinos and Latina athletes in U.S. sports. For teams, leagues, and networks, this means a marketing opportunity to expand their fan base and tap into a growing consumer market. For the various reasons discussed above, Latino and Latina athletes have taken non-traditional routes towards participation in professional and non-professional sports in the U.S. For Latinos and Latinas who did not complete high school or college, the world of sport became a vehicle for social advancement. A great majority began playing sports in the streets, sandlots, public courts, or municipal recreation centers, or while working as caddies in country club golf courses. These "back doors" of entry have shaped the nature of Latino and Latina sporting experience in the U.S. Furthermore, sport participation is a central component of Latino and Latina experiences in the U.S. and cannot be reduced to a marginal form of physical activity or a mere distraction from more serious issues of politics and economics. Sport participation has not always been easy; it has depended on a number of factors including social location, economic constraints, educational level, and scientific discourses about physical ability, as well as gender ideologies and the underlying racial structure of U.S. society.

Despite these multiple barriers, Latino and Latina athletes have made significant achievements in American sports, but these have not been individual accomplishments. Sport is too often centered on the "greatest moments," "star athletes," and spectacular feats performed in "big stadiums," and as a result individual achievements are divorced from the collective support of coaches, fans, promoters, community organizations, and neighborhoods. In addition, Latino participation in sports should move beyond the professional level to examine the relationship between athletes/teams and their communities of support, changing identities, and social networks. Unlike professional sporting events driven by big money franchises and television broadcast deals, amateur-level sports are more "unscripted" and can be more easily appropriated for social and political causes that benefit the larger community. Athletic success for Latinos has led to more educational opportunities and ultimately to successful professional careers in business, education, and politics. Latino and Latina athletes have also acted on their social conscience to defend and advance the interests of their communities.

José M. Alamillo, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor and Coordinator of the Chicano/a Studies Program at California State University, Channel Islands. His research focuses on ways in which Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans have used culture, politics, sports, and forms of leisure to build community solidarity, construct gender and ethnic identities, and forge inter-ethnic relations with other groups in order to advance politically and economically. His major works include Latinos in U.S. Sport: A History of Isolation, Cultural Identity and Acceptance, and Making Lemonade out of Lemons: Mexican American Labor and Leisure in a California Town. He received his Ph.D. in the Comparative Cultures Program at the University of California, Irvine.

Endnotes

[1] Fernando Dominguez, "Ready to Rumble: La Colonia Holding a Full House." Los Angeles Times, July 3, 1996. B3.

[2] Three books that fall in this category include Richard Lapchick, 100 Campeones: Latino Groundbreakers Who Paved the Way in Sport (West Virginia University: Fitness Information Technology, 2010); Ian C. Friedman, Latino Athletes (New York, NY: Facts on File, 2007); Jerry Izenberg, Great Latin Sports Figures (New York, NY: Doubleday & Company Inc. ,1976).

[3] On the politics of ethnic labels see Suzanne Oboler, Ethnic Labels, Latino Lives: Identity and the Politics of (Re)presentation in the United States (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1995). On the sports labor migration of Latin American athletes see Joseph Arbena, "Dimensions of International Talent Migration in Latin American Sports" in The Global Sports Arena: Athletic Talent Migration in an Interdependent World, ed. John Bale and Joseph Maguire (Portland: F. Cass, 1994), 99-111.

[4] Jorge Iber et al., Latinos in U.S. Sport: A History of Isolation, Cultural Identity, and Acceptance (Human Kinetics, 2011), 67-71.

[5] Carlos Kevin Blanton, "From Intellectual Deficiency to Cultural Deficiency: Mexican Americans, Test and Public School Policy in the American Southwest, 1920-1940," Pacific Historical Review 72 (2003): 39-62.

[6] Iber, et al., Latinos in U.S. Sport, 71-76.

[7] Elmer Mitchell, "Racial Traits in Athletics," American Physical Education Review 27, no. 4 (April 1922): 150.

[8] Elmer Mitchell, "Racial Traits in Athletics," American Physical Education Review 27, no. 5 (May1922): 201.

[9] George Sanchez, Becoming Mexican American: Ethnicity, Culture and Identity in Chicano Los Angeles, 1900-1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 87-107.

[10] José M. Alamillo, Making Lemonade out of Lemons: Mexican American Labor and Leisure in a California Town, 1880-1960 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2006), 99-122.

[11] Emory Bogardus, "The Mexican Immigrant," Sociology and Social Research, 5-6 (1927): 483.

[12] Katherine Murray, "Mexican Community Service," Sociology and Social Research 45 (1933): 548.

[13] Jorge Iber and Samuel O. Regalado, Mexican Americans and Sports: A Reader on Athletics and Barrio Life (Lubbock, TX: Texas A & M University Press, 2007), 1-15.

[14] José M. Alamillo "Playing Across Borders: Transnational Sports and Identities in Southern California and Mexico, 1930-1945" Pacific Historical Review 79, no. 3 (2010): 360-392.

[15] Phillip M. Hoose, Necessities: Racial Barriers in American Sports (New York: Random House, 1989): 90-122.

[16] Samuel Regalado, "Image is everything: Latin Baseball Players and the United States Press," Studies in American Popular Culture 13 (1994): 101-106.

[17] Carlos Ortiz, "Eet Eez Time to KO the Stereotype of the Latino Athletes." Nuestro Magazine, July 1977, 58.

[18] Daniel Frio and Marc Onigman, "Good Field, No Hit: the Image of Latin American Baseball Players in the American Press, 1871-1946," Revista/Review Interamericana 9, no.2 (Summer 1979): 199-208.

[19] José M. Alamillo, "Richard 'Pancho" González, Race and the Print Media in Postwar Tennis America," The International Journal of the History of Sport 26, no. 7 (June 2009): 947-965.

[20] Carol Griffing McKenzie, "Leisure and Recreation in the Rancho Period of California, 1770 to 1865" (Ph.D. diss., University of Southern California, 1974.

[21] Mary Lou LeCompte, "The Hispanic Influence on the History of Rodeo, 1823-1922," Journal of Sports History 12, no. 1 (Spring 1985): 21-38.

[22] Kathleen Sands, Charrería Mexicana: An Equestrian Folk Tradition (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1993); Mary Lou LeCompte, "Hispanic roots of American Rodeo," Studies in Latin American Popular Culture 13 (1994): 57-76; Richard Slatta, Cowboys of the Americas (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1990).

[23] Carol Griffing McKensie, "Leisure and Recreation in the Rancho Period of California, 1770 to 1865" (Ph.D. diss., University of California, Los Angeles, 1974), 155-156.

[24] John O. Baxter, "Sport on the Rio Grande: Cowboy Tournaments at New Mexico's Territorial Fair" New Mexico Historical Review 78, no. 3 (Summer 2003): 245-63.

[25] Glenn Shirley, Pawnee Bill (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1965).

[26] Iber et al., Latinos in U.S. Sport, 58-59.

[27] Lou Perez, On Becoming Cuban: Identity, Nationality and Culture (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999), 255-260.

[28] Adrian Burgos Jr., Playing America's Game: Baseball, Latinos, and the Color Line (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007).

[29] Bob Harkins, "Is Baseball Turning Into Latin America's Game?" NBCSports.com, at http://nbcsports.msnbc.com/id/43665383/ns/sports-baseball/, accessed July 19, 2012.

[30] Samuel Regalado, Viva Baseball! Latin Major Leaguers and their Special Hunger (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998).

[31] Burgos, Jr., Playing America's Game

[32] David Maraniss, Clemente: The Passion and Grace of Baseball's Last Hero (New York, NY: Simon & Shuster, 2006).

[33] Adrian Burgos Jr., Cuban Star: How One Nero-League Owner Changed the Face of Baseball (New York, NY: Hill and Wang, 2011).

[34] Samuel Regalado, "The Minor League Experience of Latin American Baseball Player in Western Community, 1950-1970" Journal of the West (January 1987): 65-70.

[35] Samuel Regalado, "Baseball in the Barrios: The Scene in East Los Angeles Since World War II" Baseball History 1, no. 2 (Summer 1986): 47-59.

[36] José M. Alamillo, ""Mexican American Baseball: Masculinity, Racial Struggle and Labor Politics in Southern California, 1930-1950" in Race Matters: Race, Recreation and Culture, ed. Michael Willard and John Boom (New York: New York University Press, 2002): 86-115.

[37] Richard Santillan, "Mexican Baseball Teams in the Midwest, 1916-1965: The Politics of Cultural Survival and Civil Rights" Perspectives in Mexican American Studies 7 (2000): 131-152; Alamillo, Making Lemonade out of Lemons, 123-141.

[38] Francisco Balderrama and Richard Santillan, Mexican American Baseball in Los Angeles (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2011).

[39] Mario Longoria, Athletes Remembered: Mexicano/Latino Professional Football Players, 1929-1970 (Tempe, AZ: Bilingual Press, 1997), XV.

[40] Ibid., 8-72.

[41] Jorge Iber and Samuel O. Regalado, Mexican Americans and Sports: A Reader on Athletics and Barrio Life (Lubbock, TX: Texas A & M University Press, 2007), 1-15.

[42] Jorge Iber, "On-Field Foes and Racial Misconceptions: The 1961 Donna Redskins and Their Drive to the Texas State Football Championship" The International Journal of the History of Sport 21, n. 2 (March 2004): 237-256.

[43] Michael Lewis, "The Rise of Latinos in Major League Soccer." Fox News Latino, 12 March 2012, http://latino.foxnews.com/latino/sports/2012/03/12/rise-latinos-in-major-league-soccer/, accessed June 27, 2012.

[44] David Faflik, "Fútbol America: Hemispheric Sport as Border Studies" Americana 5, n. 1 (2006): 1-12.

[45] Horacio R. Fonseca, "Pro-Soccer's Anti-Latino Game Plan." Nuestro, May 1978, 18-20.

[46] Christopher Shinn, "Fútbol Nation: U.S. Latinos and the Goal of a Homeland" in Latino/a Popular Culture, ed. Michelle Habell-Pallán and Mary Romero (New York: New York University Press, 2002), 240-251.

[47] S. Massey et al., Return to Aztlan: The Social Process of International Migration from Western Mexico (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990): 147.

[48] Marie Price and Courtney Whitworth, "Soccer and Latino Cultural Space: Metropolitan Washington Fútbol Leagues" in Hispanic Spaces, Latino Places: Community and Cultural Diversity in Contemporary America, ed. Daniel Arreola (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2004), 167-186.

[49] Javier Pescador, "Vamos Taximora! Mexican Chicano Soccer Associations and Transnational Translocal Communities, 1967-2002" Latino Studies 2, no. 3 (2004): 342-376.

[50] David Andrews, "Soccer, Race, and Suburban Space" in Sporting Dystopias: The Making and Meaning of Urban Sport Cultures, ed. Ralph Wilcox et al. (State University of New York Press, 2003), 197-220.

[51] Ilann Messeri, "Vamos, Vamos Acierteros: Soccer and the Latino Community in Richmond, California. Soccer & Society, v. 9, n.3 (July 2008): 416-427.

[52] Paul Caudros, A Home on the Field: How One Championship Team Inspires Hope for the Revival of Small Town America (New York, NY: Harper Collins/Rayo 2006).

[53] Douglas Cavanaugh, "Aurelio Herrera-Boxing's First Latino Superstar." IBRO, 27 July 2011, http://www.ibroresearch.com/?p=5112 accessed June 27, 2012.

[54] Gregory Rodriguez, "Palaces of Pain" Arenas of Mexican-American Dreams: Boxing and the Formation of Ethnic Mexican Identities," in Twentieth Century Los Angeles (Ph.D. diss., University of California San Diego, 1999), 15-21.

[55] Ibid., 110.

[56] Benita Heiskanen, "The Latinization of Boxing: A Texas Case Study" Journal of Sport History 32, no. 1 (Spring 2005): 45-66.

[57] Frances Negrón-Muntaner, "Showing Face: Boxing and Nation Building in Contemporary Puerto Rico" in Contemporary Caribbean Cultures and Societies in a Global Context ed. Franklin Knight and Teresita Martínez-Vergne (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2005), 98.

[58] Ibid., 100.

[59] Richard McGehee, "The Dandy and the Mauler in Mexico: Johnson, Dempsey, et al., and the Mexico City Press, 1919-1927" Journal of Sport History 23 no.1 (Spring 1996): 20-33.

[60] Douglas Monroy, Rebirth: Mexican Los Angeles from the Great Migration to the Great Depression (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1999), 59-62.

[61] Gregory Rodriguez, "Palaces of Pain" Arenas of Mexican-American Dreams: Boxing and the Formation of Ethnic Mexican Identities in Twentieth Century Los Angeles (Ph.D. diss., University of California San Diego, 1999), 63.[62] Bert W. Colima, Gentleman of the Ring: The Bert Colima Story( Long Beach, CA: Magic Valley Publishers, 2009).

[63] Tracy Callis and Chuck Johnston, Boxing in the Los Angeles Area, 1880-2005 (Victoria, Canada: Trafford Publishing, 2009).

[64] Dwight Chapin, "Boxing's Fading Glamour Girl: Olympic Auditorium, One a Showplace for Boxing is 50 years old today," Los Angeles Times, August 5, 1975.

[65] Fernando Delgado, "Golden But No Brown: Oscar de la Hoya and the Complications of Culture, Manhood, and Boxing," The International Journal of the History of Sport 22, no.2 (March 2005): 196-211.

[66] Richard Lapchick et al., 100 Campeones: Latino Groundbreakers Who Paved the Way in Sport (Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology, 2010): 103-106.

[67] Gabrielle Paese, "Puerto Rico's Accomplishments in Sports" Puerto Rico Herald, August 12, 2005.

[68] Iber et al., Latinos in U.S. Sport, 176-177.

[69] Michael Innis-Jimenez, "Beyond the Baseball Diamond and Basketball Court: Organized Leisure in Inter-war Mexican South Chicago" The International Journal of the History of Sport 26, no. 7 (June 2009): 906-923.

[70] Christine Marin, "Courting Success and Realizing the American Dream: Arizona's Mighty Miami High School Championship Basketball Team, 1951" The International Journal of the History of Sport 26, no.7 (June 2009): 924-946.

[71] Basketball in the Barrio: El Paso History and Culture, directed by Doug Harris (Berkeley, CA: Athletes United for Peace, 2008).

[72] Dave Zirin, "Basketball in the Barrio: Sacred Hoops" Political Affairs Magazine, June 14, 2005.

[73] Kimberley Garcia, "Still Got Swing: Golf Icon Nancy López Takes a Breather from the Green" Hispanic (June 2004): 42.

[74] Katherine M. Jamieson, "Reading Nancy Lopez: Decoding Representations of Race, Gender and Sexuality" Sociology of Sport Journal 15, no. 4 (1998).

[75] Humberto G. Garcia, Mustang Miracle (Bloomington, IN: Author House, 2010).

[76] José M. Alamillo, "Richard 'Pancho" González, Race and the Print Media in Postwar Tennis America" The International Journal of the History of Sport 26, no. 7 (June 2009): 947-965.

[77] Iber et al., Latinos in U.S. Sport, 252-255.

[78] Bill Molina, "1976 Southwestern U.S. La Raza Tennis Tournament," La Luz Magazine (April 1976), 30.

[79] Iber et al., Latinos in U.S. Sport, 271-272.

[80] Ibid., 274-275.

[81] Women's Sport Foundation, Minorities in Sports: The Effects of Varsity Sports Participation on the Social, Educational and Career Mobility of Minority Students (Center for the Study of Sport and Society, Northeastern University, August 15, 1989).

[82] "No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance..." Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, Public Law No. 92-318, 86 Stat. 235 (June 23, 1972), codified at 20 U.S.C. sections 1681 through 1688.

[83] Kathy Jamieson, "Advance at Your Own Risk: Latinas, Families, and Collegiate Softball" in Americans and Sports: A Reader on Athletics and Barrio Life, ed. Jorge Iber and Samuel O. Regalado (Lubbock: Texas A & M University Press, 2007): 213-232.

[84] Kathy Jamieson, "Occupying a Middle Space: Toward a Mestiza Sports Studies" Sociology of Sport Journal, v. 20(2003): 1-16.

[85] Lapchick, 100 Campeones, 335-337.

[86] Dan Cobian, "Women in Baseball: Latinas in the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League" http://www.chicla.wisc.edu/publications/workingpapers/DanCobian.html, accessed June 28, 2012.

[87] Barbara Gregorich, Women at Play: The Story of Women in Baseball (San Diego, CA: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1993), 150-157.

[88] Iber et al., Latinos in U.S. Sport, 136-137.

[89] Chris Marrou, "Tenayuca The Troublemaker" KENSS 5, Oct. 15, 2009; "El Equipo Femenino de Basketball Modern Maids," La Prensa, March 5, 1933.

[90] Zaragosa Vargas, "Tejana Radical: Emma Tenayuca and the San Antonio Labor Movement during the Great Depression" The Pacific Historical Review, 66, no. 4 (November 1997): 553-580.

[91] "Latinas Unified On the Soccer Field," Hispanic Magazine 12, no. 6 (June 1999).

[92] Ivan Orozco, "Overcoming Obstacles Latino girls want to play championship soccer, but must kick hurdles out of the way," San Diego Union-Tribune, March 5, 2009.

[93] Kelly Whiteside, "Superstar Marta's Magical Feat," USA Today, July 8, 2009.

[94] Delilah Montoya, Women Boxers: The New Warriors (Houston TX: Arte Publico Press, 2006).

Part of a series of articles titled American Latino/a Heritage Theme Study.

Previous: American Latino Theme Study: Arts

Last updated: August 31, 2021