Last updated: July 21, 2023

Article

Knife River: Early Village Life on the Plains (Teaching with Historic Places)

Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site

High on a bluff overlooking the Knife River in the Upper Missouri River valley, soft winds ruffle the lush grasses that cover, but do not obscure, circle upon circle of raised earth with central depressions. These depressions mark all that remains of a once lively village. In the late 18th century, while European colonists were fighting a revolution with England in the eastern part of the continent, these villagers were conducting their centuries-old trade with remote tribal groups; fashioning weapons needed to hunt the big game that shared the rolling hills; tending their gardens of squash, pumpkin, beans, sunflowers, corn, and tobacco; and carrying on all the other occupations of daily life. From the ceremonial plaza—a spot of land that was once the center of village activities—one can look to the northward hills and see trails left from the travois, sled-like carriers used by hunters and traders.

Looking downward toward the slow-moving river, partly obscured by the cottonwood and willow trees that line the river banks, one can easily imagine groups felling trees to be hauled up the hill and prepared as support beams for new or reconstructed earthlodges. One can almost hear children splashing in the river's cool waters, swimming and playing about in the round bull boats that were used to cross the river.

It is possible to imagine such scenes because we know what to look for. The writings and illustrations of European American visitors to the villages during the late 18th and early 19th centuries provide a historical record of Plains Indians that is unparalleled in its abundance of information, detail, and diversity of sources. Recent archeological studies have added rich information about the site that goes back at least 3,500 years.

About This Lesson

The lesson is based on the National Register of Historic Places nomination file, "Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site," and other sources. It was published in 2000. It was written by Fay Metcalf, education consultant, and edited by the Teaching with Historic Places staff. TwHP is sponsored, in part, by the Cultural Resources Training Initiative and Parks as Classrooms programs of the National Park Service. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into the classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Time Period: 18th and 19th centuries

Topics: The lesson could be used in American history units on American Indian culture or westward movement during the 18th and 19th centuries.

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

Knife River: Early Village Life on the Plains relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 1: Three Worlds Meet (Beginnings to 1620)

- Standard 1A: The student understands the patterns of change in indigenous societies in the Americas up to the Columbian voyages.

Era 2: Colonization and Settlement (1585-1763)

- Standard 1B: The student understands the European struggle for control of North America.

Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

- Standard 1A: The student understands the international background and consequences of the Louisiana Purchase, the War of 1812, and the Monroe Doctrine.

- Standard 1B: The student understands federal and state Indian policy and the strategies for survival forged by Native Americans.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

(National Council for the Social Studies)

Knife River: Early Village Life on the Plains relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme I: Culture

- Standard D: The student explains why individuals and groups respond differently to their physical and social environments and/or changes to them on the basis of shared assumptions, values, and beliefs.

- Standard E: The student articulates the implications of cultural diversity, as well as cohesion, within and across groups.

Theme II: Time, Continuity and Change

- Standard B: The student identifies and uses key concepts such as chronology, causality, change, conflict, and complexity to explain, analyze, and show connections among patterns of historical change and continuity.

- Standard C: The student identifies and describes selected historical periods and patterns of change within and across cultures, such as the rise of civilizations, the development of transportation systems, the growth and breakdown of colonial systems, and others.

Theme III: People, Places, and Environment

- Standard A: The student demonstrates an understanding of concepts such as role, status, and social class in describing the interactions of individuals and social groups.

- Standard H: The student examines, interprets, and analyzes physical and cultural patterns and their interactions, such as land use, settlement patterns, cultural transmission of customs and ideas, and ecosystem changes.

Theme VI: Power, Authority, and Governance

- Standard A: The student examines persistent issues involving the rights, roles, and status of the individual in relation to the general welfare.

- Standard C: The student analyzes and explains ideas and governmental mechanisms to meet needs and wants of citizens, regulate territory, manage conflict, and establish order and security.

Theme VII: Production, Distribution, and Consumption

- Standard I: The student uses economic concepts to help explain historical and current developments and issues in local, national, or global contexts.

Objectives for students

1. To describe the life of the Hidatsa and Mandan groups in the early 19th century and to explain how the villagers shaped their environment and adapted to it;

2. To compare the seasonally nomadic Plains villagers with the popularized history of nomadic horse-culture Indians;

3. To use archeological and historical data to understand the daily life of the villagers;

4. To discover American Indian groups who once lived in their region and compare their cultures to the Hidatsa and Mandan peoples.

Materials for students

The materials listed below can either be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students.

1. Four maps of Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site and trading patterns of the villages' inhabitants;

2. Two readings on the daily life of the Hidatsa and Mandan tribes and the impact of western contact;

3. One photograph of Big Hidatsa Village today;

4. One drawing of the interior of an earthlodge;

5. Two paintings of the Hidatsa and Mandan villages.

Visiting the site

The Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site is administered by the National Park Service. The area is located 60 miles north of Bismarck, North Dakota, and can be reached via US Highway 200A. For more information, contact the Superintendent, Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site, P.O. Box 9, Stanton, ND 58571, or visit the park's web pages.

Getting Started

Inquiry Question

North Dakota Department of Transportation

What do you think may have caused these circular depressions in the landscape?

Setting the Stage

The 1,758-acre Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site in North Dakota preserves historic and archeological remnants of the culture and agricultural lifestyle of the Northern Plains Indians. More than 50 archeological sites suggest a possible 8,000-year span of inhabitation. In the 18th and early 19th centuries, the site was a relatively urban settlement with three large villages occupied by the Hidatsa and Mandan tribes. Three of the most striking cultural aspects of the Hidatsa and Mandan tribes were their practice of living in large villages with houses set close together, their skill as architects and builders, and the richness of their culture, due in part to their role as brokers in a widespread trading network and their control of an important product--Knife River flint--which was valued for the quality of tools and weapons it produced.

As centers of trade, these villages attracted Indians and European Americans alike. Direct contact with Europeans began in 1738 when Frenchmen from Canada came to the region. Soon British and Canadian traders began to filter into the region for the prized beaver pelts and for the skins of wolf, fox, and otter. The Knife River villages also became known as a trading post for high quality horses that would be exchanged for guns and ammunition. In this manner, the Hidatsas and Mandans obtained considerable affluence and power among the Northern Plains tribes.

Locating the Site

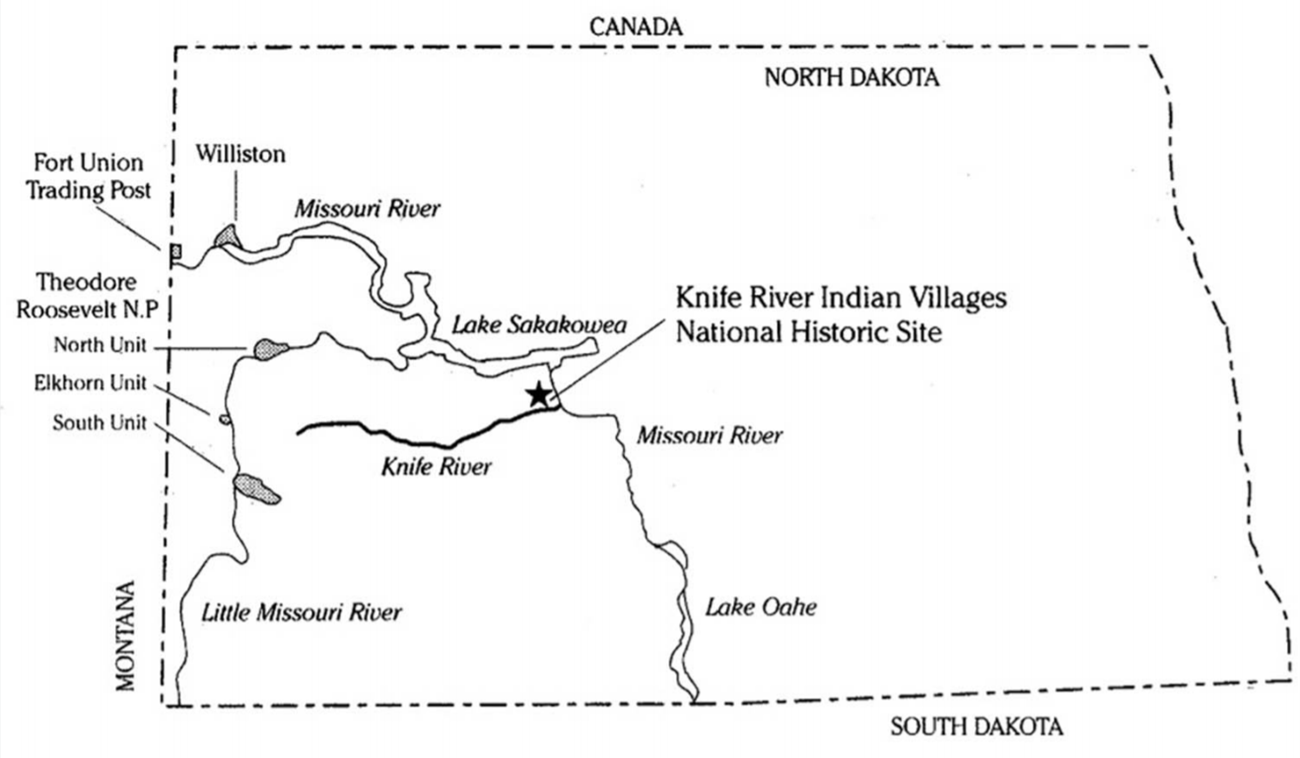

Map 1: North Dakota

Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site

The Knife River is a tributary of the Missouri River, a water route early Euro-Americans hoped could lead them to the Pacific Ocean. The Missouri also provided a transportation system for both Indian and Euro-American trappers and traders.

Questions for Map 1

1) Locate the Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site on Map 1. How would you describe its location?

2) What might have been some advantages to this location?

Locating the Site

Map 2: Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site

National Park Service

For centuries the Upper Missouri River valley drew Northern Plains Indians to its wooded banks and rich soil. These groups were essentially agricultural-based societies who lived in villages along the Missouri and its tributaries. At the time of European contact, these communities were the culmination of 700 years of settlement in the area. The Hidatsas settled Awatixa Xi'e Village around 1525, Hidatsa Village around 1600, and Awatixa Village (Sakakawea Site) in 1796. Intermarriage and trade between the Hidatsas and Mandans cemented their relationship, and eventually the two cultures became almost indistinguishable. With the Arikaras to the south, they formed an economic force that dominated the region.

Questions for Map 2

1) Examine Map 2, a detailed map of the villages that today make up Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site. Use the map scale to compute the distance between the villages. What do you think the distances between the villages might suggest about the relationship between and within the groups?

Locating the Site

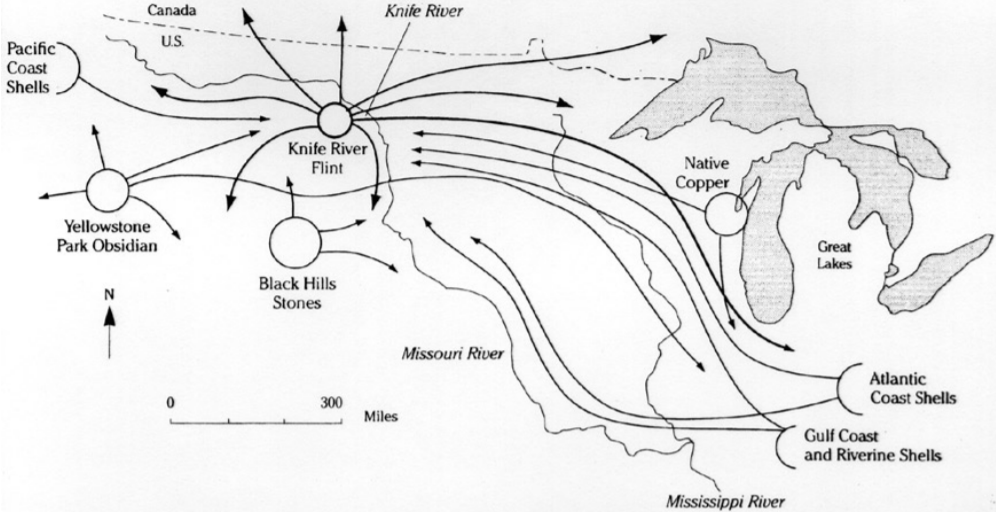

Map 3: Northern Plains prehistoric trading system

Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site

Locating the Site

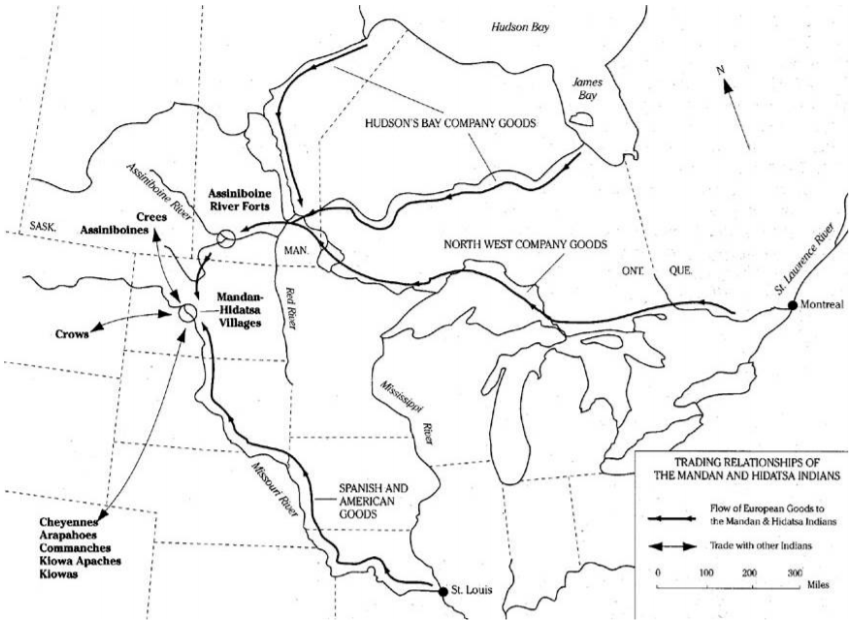

Map 4: Trading relationships of the Mandan and Hidatsa Indians, c. 1800

Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site

The commodities traded in prehistoric times between Indian groups were mostly garden produce, hides, meat, and other perishable items of the hunt. While little evidence of these goods has survived, certain nonperishable artifacts traded into the villages from distant places provide a few clues. Some of the best evidence for prehistoric trade is found in the stone used to make everyday tools and implements. Knife River flint, which the villagers traded widely, is one such stone of particular importance: it is a dark brown, glassy material which was in great demand for producing durable, sharpedged implements. Exotic materials, including shells and copper, moved through trade routes to Knife River villages in small quantities, usually in the form of pendants and beads used for personal adornment.

The earliest European visitors observed the villagers to be shrewd traders, exchanging corn, beans, squash, and other horticultural products with their nomadic neighbors for the dressed hides, feathers, lodge covers, and clothing articles of widely dispersed peoples such as the Assiniboine, Plains Cree, Crow, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Klowa, Kiowa-Apache, and Comanche. Their experience within this trading network prepared the Hidatsas and Mandans to be discerning traders with the Europeans. The earliest contacts were not with Europeans themselves, but with European products. These were obtained through a network of other Indians who were trading furs directly with the French and other Europeans at forts and contact points along the eastern border of the continent. Glass beads and iron fragments dating from 1600-50, found at the Hidatsa Village and Awatixa Xi'e Village, are evidence of this early trade at Knife River.

Questions for Maps 3 and 4

1) Maps 3 and 4 show trading relationships in both prehistoric and historic times. What is significant about the place the Knife River region held in both time periods?

2) List the trade items noted on Map 3. What are potential uses of these items?

3) Determine the trading partners of the Hidatsas and Mandans during historic times. Place a check mark beside the names of Indian nations you recognize. Which of these groups are mentioned in your American history textbook?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: A Village Life in the Upper Missouri River Valley, c. 1740-1845

A Way of Life

The Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara tribes shared a culture superbly adapted to the conditions of the Upper Missouri River valley. Their summer villages, located on natural terraces above the river, were ordered communities with as many as 120 earthlodges. An earthlodge is a circular, earth-covered structure which usually has its entire interior area dug out to one foot below the ground surface. Each earthlodge sheltered an extended family of 10 to 30 people from the region's extreme temperatures. The summer villages were strategically located for defense, often on a narrow bluff with water on two sides and a palisade (a fence of upright logs or poles set on end into the ground for enclosure or defense) on the third. In winter the inhabitants moved into smaller lodges along the bottomlands, where trees provided firewood and protection from the cold wind.

In this village society, men lived in the household of their wives, bringing only their clothes, horses, and weapons. Women built, owned, and maintained the lodges and owned the gardens, gardening tools, food, dogs, and horses. Related lodge families from numerous villages made up clans, whose members were expected to help and guide each other but who were forbidden to marry other clan members. Clans were competitive, especially in war, but it was the agegrade societies, transcending village and clan, that were looked to for personal prestige. Young men purchased membership in the lowest society at 12 or 13 years of age, progressing to higher and more expensive levels as they reached the proper age. Besides serving as warrior bands, each group was responsible for a social function: policing the village, scouting, or planning the hunt. Most important, the age-grade societies were a means of social control, setting standards of behavior and transmitting tribal lore and custom.

The roles of men and women were strictly defined. Men spent their time seeking spiritual knowledge, hunting, and horse raiding—all difficult and dangerous but relatively infrequent undertakings. Women performed virtually all the routine work: gardening, preparing food, maintaining the lodges, and, until the tribes obtained horses, carrying burdens. The lives of these people were not totally devoted to subsistence, however. They made time for play. Honored storytellers passed on oral traditions and moral lessons, focusing on traditional tribal values of respect, humility, and strength. The open area in the center of each village was often given over to dancing and to ritual, which bonded the members of the tribe and reaffirmed their place in the world.

The Village Economy

Agriculture was the economic foundation of the Knife River people, who harvested much of their food from rich flood-plain gardens. The land, which was controlled by women, passed through the female line, and the number of women who could work determined the size of each family's plot. They raised squash, pumpkin, beans, sunflowers, and, most important, tough, quickmaturing varieties of corn that thrived in the meager rainfall and short growing season of the Knife River area. Summer's first corn was celebrated in the Green Corn ceremony, a lively dance followed by a feast of corn. Berries, roots, and fish supplemented their diet, while upland hunting provided buffalo meat, hides, bones, and sinew.

These proficient farmers traded their surplus produce to nomadic tribes for buffalo hides, deer skins, dried meat, and other items in short supply. At the junction of major trade routes, they became brokers, dealing in goods within a vast trade network: obsidian from Wyoming, copper from the Great Lakes, shells from the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Northwest, and, after the 17th century, guns, horses, and metal objects. High quality flint quarried locally found its way to tribes spread over a large part of the continent through this trading system.

The Battle and the Hunt

In this tribal culture, raiding and hunting were the chief occupations of the men. When conflict was imminent, a war chief assumed leadership of the village. Although horses and loot often came from the raids, the conflicts were more important as stages on which warriors could prove themselves. Hunting parties were planned in much the same fashion, with a respected hunter choosing participants and planning the event. Prowess in battle and hunt led to status in the village, both individually and for the hero's society and clan. Ambitious young men would risk leading a party, which was highly rewarding if successful but ruinous to their reputation if not.

The primary weapon was the bow and arrow, used along with clubs, tomahawks, lances, shields, and knives. Even more prestigious than wounding or killing an enemy was "counting coup"—touching him in battle. But ambition did not spur every action: warriors often had to defend the village against raids by other tribes. When men prevailed in battle, the women would celebrate with dance and song.

Spirit and Ritual

Spirits guided the events of the material world, and from an early age, tribal members (usually male) sought their help. Fasting in a sacred place, a boy hoped to be visited by a spirit—often in animal form—who would give him power and guide him through life. The nature of the vision reported to his elders determined a man's role within the tribe. If directed by his vision, he would make a great sacrifice to the spirits, spilling his blood in the Okipa ceremony. The Okipa was the most important of a number of ceremonies performed by Mandan clans and age-grade societies to ensure good crops, successful hunts, and victory in battle. Ceremonies could be conducted only by those with "medicine," which was a bundle of sacred objects associated with tribal mythology purchased from a fellow clan or society member. With bundle ownership came responsibility for knowledge of the songs, stories, prayers, and rituals necessary for spiritual communication. Certain bundle owners were looked upon as respected leaders of the tribe.

Reading 1 was compiled from The National Park Service visitors' guide for Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site.

Questions for Reading 1

1) What natural conditions of the Upper Missouri River valley did the village Indians use to their advantage?

2) These villagers had a governmental structure quite different from those we know today. What elements of their political system fostered a well-ordered society?

3) What evidence is presented that gender roles were clearly defined?

4) The villagers were a preliterate society, meaning they did not have a written language. How do you think they educated their children?

5) How did the villagers make their living?

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: Western Contact

Because of their role as trade centers and their location on a tributary of the Missouri River, a major artery of western travel, the villages at Knife River received many European American visitors—men drawn by the prospect of wealth in the fur trade, exploration and national expansion, and simple curiosity. For the most part, the Mandans and Hidatsas received these outsiders with openness and hospitality, providing a welcome respite to weary travelers and an important staging area for further travel and fur-trade operations in more remote regions. This frequent and sustained contact with a different culture ultimately transformed the traditional way of life for the Hidatsa and Mandan tribes, while contributing to the economic development and westward expansion of America.

When trader Pierre de la Verendrye—a French-Canadian colonial officer responsible for opening up much of the western Great Lakes region—walked into a Mandan village in 1738, he found a society at the height of its prosperity. Verendrye's arrival marked the first recorded European visit to the Indians of the Upper Missouri River valley and began a relentless process that transformed a culture within 100 years. At first the three tribes remained relatively isolated, although there were increasing contacts with French, Spanish, English, and American fur traders. Their culture was still healthy when explorer David Thompson reached the area in 1797, but the pace of change quickened after the Lewis and Clark expedition visited the tribes. The expedition spent the winter of 1805 a few miles south of the Knife River villages, where the men built a three-sided fort, which they named Fort Mandan. The men of the expedition frequently visited with the villagers. During this same winter, fur trapper Toussaint Charbonneau and his Shoshone wife, Sakakawea, were hired to guide the explorers westward. Other explorers, including Prince Maximillian of Weid-Neuwied, whose ethnological and natural history notes are still a primary reference on the Mandans and Hidatsas, and artists such as Karl Bodmer and George Catlin, drew clear portraits of a society in transition. Naturalist John James Audubon visited in 1843, but by then the culture had changed radically.

An influx of European American fur traders set up new trade patterns that undermined the tribe's traditional position as brokers in a long-established American Indian trade network. Villagers grew more dependent on European goods such as horses, weapons, cloth, and iron pots. Diseases carried by the Europeans and overhunting of the bison further weakened the community. There were several small pox epidemics between 1780 and 1856: the epidemic of 1837-38 was especially tragic with a mortality rate of almost 60 percent. In 1845 most of the remaining Hidatsas and Mandans joined together to establish Like-a-Fishhook Village some 40 miles northwest of the Knife River villages. In 1862 the remaining Arikara joined them, and the tribes became known as the Three Affiliated Tribes. In 1865 they were forced to leave their village and move onto the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation. Today the tribes continue to practice their traditional ways.

Reading 2 was compiled from the National Park Service visitors' guide for Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site, and Thomas D. Thiessen, "Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site Archeological District" (Mercer County, North Dakota) National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1987.

Questions for Reading 2

1) Why did the Hidatsa and Mandan receive many European American visitors? How did the villagers treat them?

2) List the visitors mentioned in the reading. What were their motives for traveling to the Knife River area?

3) How did these visitors change the Hidatsa and Mandan way of life? What happened in later years to the tribes and their allies, the Arikara?

Visual Evidence

Photo 1: Aerial View of Big Hidatsa Village

North Dakota Department of Transportation

Questions for Photo 1

1) Examine the photograph. Based on what you have learned about the Knife River Indian Villages, what caused the circular depressions evident in Photo 1?

2) What can these depressions tell us about the people who once inhabited the area?

Visual Evidence

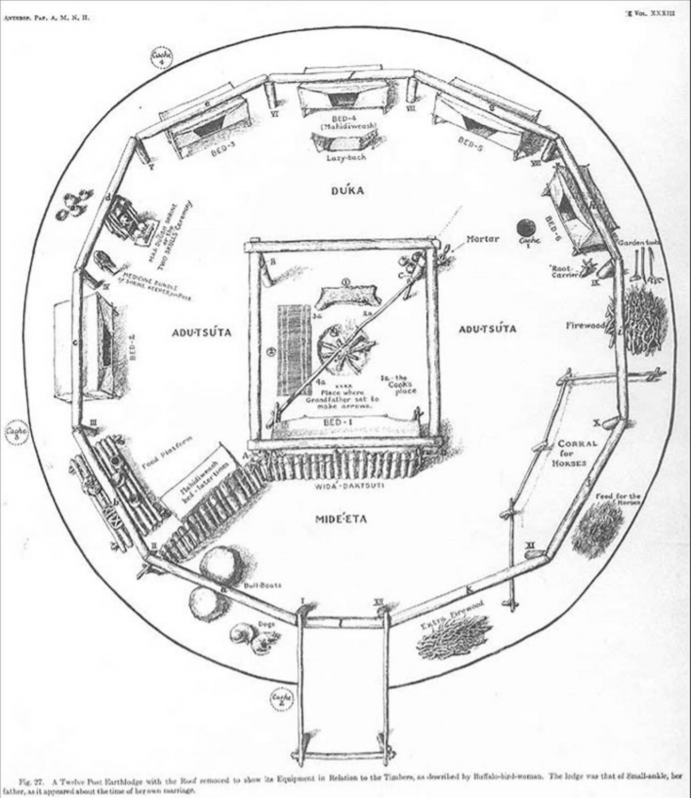

Drawing 1: Aerial view of a twelve-post earthlodge

American Museum of Natural History, Neg. no. 2A19110

An earthlodge is a circular, earth-covered, wooden structure. The interior is usually dug out to one foot below the ground surface. The outside edge of the excavated area has a ring of poles set into it, forming a wall. Four central roof support posts with rafters across them form a square. Poles are leaned against the Rafter Square from the top of the pole wall and across the Rafter Square, leaving only a central smoke hole. Brush is placed over the wooden frame on all sides, and the entire structure is covered with earth. The lodge is entered by a ladder through the central smoke hole or through a tunnel-like wooden entry passage built into the wall. Earthlodges were 30 to 60 feet in diameter and 10 to 15 feet high. Each housed an extended family of up to 20 people along with the family's best hunting and war horses.

Questions for Drawing 1

1) Examine the earthlodge layout. What activities do you think took place in the earthlodge?

2) Why do you think the horses were kept inside?

3) What do you think it might have been like to live in an earthlodge like this?

Visual Evidence

Painting 1: Hidatsa Village, Earth Covered Lodges, on the Knife River, by George Catlin

WikiMedia Commons

Visual Evidence

Painting 2: Bird's Eye View of the Mandan Village, by George Catlin

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison, Jr. Available on WikiMedia Commons.

While the villagers spent a good deal of time outdoors in mild weather, the climate was harsh, with recorded winter temperatures often as low as 45 degrees below zero. In winter people moved to temporary lodges built among the trees beside the Knife River.

Questions for Paintings 1 and 2

1) How would you describe the setting?

2) What activities does Catlin show the Hidatsas and Mandans participating in?

3) How would you describe the way Catlin shows the villages and their inhabitants in these paintings?

4) Given the overall harsh climate of North Dakota, why do you think that both of the paintings George Catlin chose to show the villagers on a rare warm day?

Putting It All Together

The following activities will help students better understand art as a historical resource and characteristics of different American Indian cultures.

Activity 1: Drawing Conclusions from Art

George Catlin was a white American artist who was known for his depictions of Native Americans. With a partner, have students examine Paintings 1 and 2, looking closely and reading the paintings as they would a book, from left to right and from top to bottom. Ask them to go over the paintings several times, each time attempting to pick up new details. Some techniques include dividing the paintings into grids, or looking at the background first, then the foreground, next, groups of objects or people, individual items, portions of the human body and so on. Summarize the evidence in the paintings and discuss the image of the Hidatsa and Mandan Indians as portrayed by Catlin.

Now ask students to view these Hidatsa, Mandan, and Arikara art pieces created around the same time as Catlin’s paintings. Ask students to use the same techniques they used in viewing Catlin’s paintings. Summarize the evidence in the images and discuss the image of Hidatsa, Mandan, and Arikara Indians as artists from these cultures depicted themselves.

- Bloody Knife (NeesiRAhpát), “The Exploits of Poor Wolf,” Arikara

- Bloody Knife (NeesiRAhpát), “Painting,” Arikara

- Unknown Artist, “Pictured Sheet,” Hidatsa, Arikara, or Mandan

- Unknown Artist, “Pictured Buffalo Robe,” Hidatsa, Arikara, or Mandan [note: be sure to zoom in on the images]

- Unknown Artist, “Deer-Hide,” Hidatsa

[Note: if students are interested in viewing more Native American art, the Smithsonian online collection is a wonderful resource.]

How were the Hidatsa, Mandan, and Arikara depictions different from Catlin’s? Encourage students to go beyond questions of artistic style to discuss the elements of the Native American cultures that each artist chose to emphasize. Why is it helpful to look at Native American artwork when trying to learn about Native American cultures?

Activity 2: Making Comparisons

Ask the students to examine an American history textbook account of the Plains Indians, noting similarities and differences between the Knife River villagers and tribes such as the Sioux and the Cheyenne (all these groups are considered Plains Indians). The Hidatsa, Mandan, and Arikara tribes obtained horses along with the other Plains groups in the mid 1700s. Why didn't the villagers adopt the typical American Indian horse culture? Most of the other groups had also been farmers at one time, but they gave up their farms to lead a more nomadic existence. What characteristics of the Knife River villagers might account for their continued occupation of the village sites?

Activity 3: Researching Local Tribes

Have the students compare what they have learned in this lesson with materials in an American history textbook that use sites such as prehistoric cliff dwellings or mound cultures to illustrate early life in the Americas. Ask them to outline differences and similarities. Next, instruct the students to research the Native American groups who lived in their region. Were they more like cliff dwellers than Hidatsa villagers? Were they engaged in early trade? How do their houses, clothing, and other items compare with those of the Knife River villagers? If possible, take the students to visit a local museum that displays Native American artifacts from their region. If this can be arranged, have the students construct a matrix of cultural items as they did for the Knife River society. Back in class, have the students compare the matrices and then draw conclusions about why the cultures might differ (the environment, available resources, proximity to oceans, and proximity to other tribes, for example).

Additional Resources

Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site

Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site is a unit of the National Park System. The park's web pages offer extensive information about the site. Students can learn the history of Knife River, take a tour of an earthlodge, learn about American Indian village life and culture, and view photos from the park's collection.

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress's Digital Collections page is an excellent source for documents and images. Students can search "History of the American West, 1860-1920", a collection of more than 30,000 photos providing documentation of more than 40 American Indian tribes living west of the Mississippi River.

Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation's Three Affiliated Tribes

The Tribes' website is an excellent resource for the Fort Berthold Reservation and tribal history. Included is information on the three tribes as well as an outline of the similarities and differences between the three groups prior to, and after, the settlement of their native territory by white peoples.

North Dakota History

The North Dakota History web pages offer an excellent resource for Native American history in North Dakota before and after the settlement of the area by white Americans. Taken from the North Dakota Centennial Blue Book 1889-1989, this site explains the adaptation of distinct Native American groups from the time the first white explorers arrived. The groups included the Dakota or Lakota nation, Assiniboine, Cheyenne, Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara.

Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe

The Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe's web pages provide a brief background of the Cheyenne and the Lakota Tribes. Students can use this site to learn about the Cheyenne and Lakota cultures and compare them to the Hidatsa and Mandan cultures.