NPS Photo/ S. Muether

Many people have heard of Soapy Smith – the so-called “King of the Frontier Con Men” – but not everyone realizes that the building Soapy operated out of during his brief tenure in Skagway has an equally interesting history as the man.

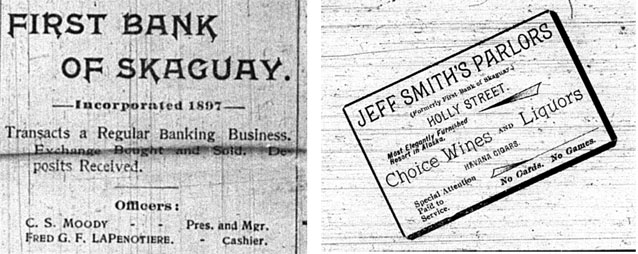

Daily Alaskan, July 11, 1898 (left). Skaguay News, June 7, 1898 (right).

First Bank of Skaguay

The small false-fronted, single-story, wood frame building currently located on the south side of Second Avenue in Skagway was originally located on the north side of Sixth Avenue between Broadway and State streets. It was initially a solid vertical board structure with a center door flanked by two windows. It was probably the first home of the First Bank of Skaguay. According to a news story, the First Bank of Skaguay opened for business on December 21, 1897 (Skaguay News 1899:3). Although the exact date for the construction of this building is unknown, it was probably built shortly before the opening date for the bank and may have been built specifically for this bank.

The First Bank of Skaguay advertised itself as having a Capital Stock of $25,000 (over $636,000 in today’s dollars). C. S. Moody was President and Manager and S. W. Aldrich was Vice President (Skaguay News 1898a:2). Business was good and by the spring of 1898, the bank had moved to new offices located in the Moore Hotel (currently the Portland House) on the southeast corner of Fifth Avenue and State Street. By December 1898 the Canadian Bank of Commerce, with $6,000,000 in assets (over $152,000,000 in today’s dollars), had established a branch agency in Skagway (Skaguay News 1898d:4; Daily Alaskan 1899b:2) right next door in the Moore Hotel (Daily Alaskan, 1900). For a brief period of time the Moore Hotel was known as the Bank Building with the two banks operating out of the same building. Probably because of this competition, The First Bank of Skaguay went into receivership, and by 1903 creditors of this institution were being paid approximately 28 percent of what was due them (Daily Alaskan 1903:1). The Skagway agency for the Canadian Bank of Commerce later moved to a building on the north side of Fifth Avenue and stayed in town another 10 years.

According to the tax records and a title search, the First Bank of Skaguay continued to own what would become Soapy’s Parlor until 1900 but after the bank moved out, it was sublet by Frank Clancy perhaps in partnership with Jefferson Randolph “Soapy” Smith, Jr. “Soapy” Smith, first arrived in Skagway with a few members of his gang sometime in August 1897 (Bearss 1970:183), however, he did not open his Parlor until May 1898 which leaves open the question of where he based his operations and just how extensive they were until then.

Changing Times

Soapy altered the building’s false front by moving the door to the right (east) side and the windows to the left (west) side presumably in order to accommodate his bar. He does not appear to have changed the doors or windows, just moved them. He also added horizontal shiplap drop siding to the front, a large trim piece (cornice board) to the top of the false front, and, in addition to the façade sign, an illuminated projecting sign in the center, and two small projecting signs on either side of the building’s front. The sides and presumably the rear were board and batten. Metal bars were installed over the front windows presumably because of the rough elements in town at the time. It’s interesting that the bank didn’t feel such bars were necessary.

After Soapy’s death in a gunfight on July 8, 1898, the Parlor became, in short order:

- The Mirror Saloon (?) (Frank Clancy, proprietor) (Skaguay News 1898c:2);

- Clancy’s, A “Gentleman’s Resort,” (Frank Clancy / Walter Rittinger, proprietors) (Daily Alaskan 1899a:2) (figure 10);

- The Clancy Café “Reopened under new management” as a restaurant (Wm Gafford, proprietor) (Daily Alaskan 1899c:4 and d:1);

- The Sans Souci (bastard French for “without a care”) Restaurant and Oyster Parlor (Daily Alaskan 1899e:1) (figure 11).

Aside from new signs to reflect the new businesses, the building underwent little change during this period.

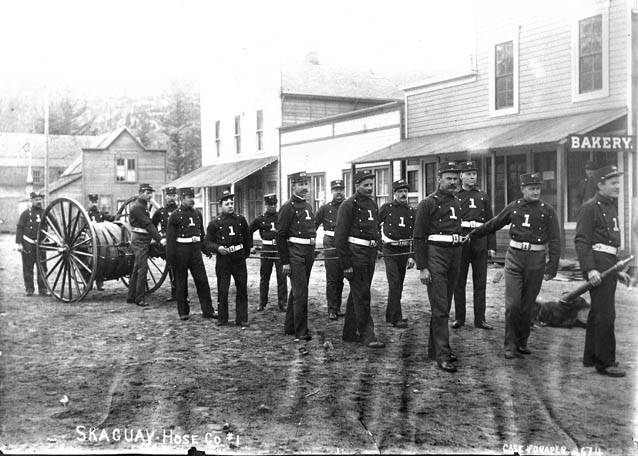

NPS, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, George and Edna Rapuzzi Collection, KLGO 55918. Gift of the Rasmuson Foundation.

Hook and Ladder Co.

The Skagway City Council minutes of November and December 1900 indicate that Lee Guthrie (then owner of the Parlor), agreed to allow the Skagway Volunteer Fire Department to use the Parlor for the Hook and Ladder Company free of charge although later there is indication of a $75 per year rental charge ($1,908 in today’s value) on this building and the Hose Company building next door. On January 9, 1901, the City was given a bill of $69 ($1,755 in today’s dollars) for altering the Parlor to fit the needs of the Hook and Ladder Company, which included the addition of a brick chimney (Mulvihill 1993). The 1914 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map and a photograph taken around 1915 confirm the major changes the Parlor underwent in order to convert it from a restaurant to the “Hook & Ladder Truck and Hose Shed” or garage.

Once again, the front underwent a considerable change. The front door was moved way to the left (west) side and both front windows were removed to make way for a set of double garage style doors, with smaller windows inside the doors, to accommodate the hook and ladder truck. At the same time this exterior change was being undertaken, the insides would have been gutted to make way for the Hook & Ladder Truck itself. The “truck” was really a small wagon pulled by the men of the Hook & Ladder Company.

In 1916, the land the Parlor sat on was bought by the Bank of Alaska for their new concrete bank headquarters building. Construction started on the new building that year and the bank was formally opened for business in the new building on March 20, 1917 (Daily Alaskan 1917:4). Photographs, tax records, and the Daily Alaskan newspaper all clearly indicate that the Parlor and adjacent Fire Department Hose House was moved across Sixth to the south side of the avenue in late April 1916, to make way for the new bank building. Workmen took two days to roll the two wooden frame buildings to their new locations. The Sanborn Fire Insurance map of 1948 and a number of photographs also confirm the new location.

NPS, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, George and Edna Rapuzzi Collection, KLGO 55919. Gift of the Rasmuson Foundation.

Martin Itjen's Museum

In 1935, longtime Skagway resident, former Stampeder, and early tourism advocate Martin Itjen took over the building and began the first restoration, creating the “Jeff. Smiths Parlor Museum.” Itjen, a German immigrant born on January 24, 1870, found his way to Alaska from Jacksonville, Florida, with his wife Lucille in 1898. In Skagway, he worked at several professions including town undertaker and coal deliverer. He also operated the Bay View Hotel, opened the first Ford Motorcar dealership in town and ran the Skagway Street Car Company. But most importantly he was the premiere figure in Skagway tourism and remained a tireless tourism promoter until his death in 1942.

Itjen bought the Hook & Ladder Company shed and restored it as the Parlor. The Parlor’s interior had been gutted and the front substantially altered to make way for the Skagway Volunteer Fire Department’s Hook and Ladder truck, so Itjen had his work cut out for him. Itjen rebuilt the whole false front to reflect his understanding of the original Parlor construction. Certain features of the new front, however, do not match the original. The four main points of discrepancy are:

- The new siding is thinner than the original) (26 boards in figure 7 vs. 27 boards)

- The top of the door and window frames are at the same height on the Itjen remodel (figure 16) but not on the original;

- The Itjen trim piece (cornice board) at the top of the front is considerably smaller than the original trim piece; and

- The front door is quite different in appearance.

In addition, the illuminated exterior sign is missing in Itjen’s new design and the main façade sign just below the cornice board appears to be slightly larger than the original. The bars on the windows are also missing as is the apostrophe in the “Smith’s” portion of the Itjen sign leading me to suspect that Itjen based his remodel on several photographs of the original Soapy front, where the top of the sign (and the apostrophe) was covered by the Decoration Day and Fourth of July banners. It appears, therefore, that Itjen put in new or used windows, a new or used door, and new or used horizontal shiplap drop siding on the front. He would have also had to buy new or used furnishings for the interior. He also attached a building or two at the back to enlarge the display space although these buildings were attached to the rear of Soapy’s Parlor off-center.

NPS Photo/ S. Muether

Passing the Torch

The Jeff Smith Parlor Museum was an important part of Itjen’s Skagway tours until his death in 1942. After World War II, Itjen’s friends kept the museum open until 1950. In 1945, George Rapuzzi took over responsibility for paying taxes on the lot from Itjen’s wife (who died in 1946) but apparently kept the museum closed during the 1950s for lack of time and money to repair the building. In 1963, the museum was moved again, this time by George Rapuzzi, to the south side of Second Avenue, near Broadway where it rests today. George restored the building a second time and reopened it once again as the Jeff Smiths Parlor Museum, probably in summer of 1967.

Following George’s death in 1986, the museum was again closed. Edna Rapuzzi (George’s wife) died in 1988, and having no children of their own, the Rapuzzi estate passed to Edna’s niece Phyllis Brown. In April 2007, Brown sold the Rapuzzi collection of artifacts and several historic buildings including the Parlor, to the Alaska-based Rasmuson Foundation. The Foundation in turn donated the collection, the Parlor, and the other buildings to Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park and the Municipality of Skagway in December 2008.

The National Park Service has spent eight years and about $1 million dollars completely restoring the Jeff Smiths Parlor Museum so it once again tells the colorful story of Skagway and her citizens. The restored Jeff. Smiths Parlor had grand opening on April 30, 2016 full of festivities and stories about Martin Itjen the inventor and visionary and George Rapuzzi the collector and bearer of the torch!

Discover the wonders of Jeff. Smiths Parlor in person or through a virtual tour.

About this article

This article was originally a 2010 KNHS radio broadcast researched and written by Karl Gurcke, historian for Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park.

Last updated: October 26, 2021