Last updated: October 6, 2023

Article

Immigration and the Great War

Library of Congress

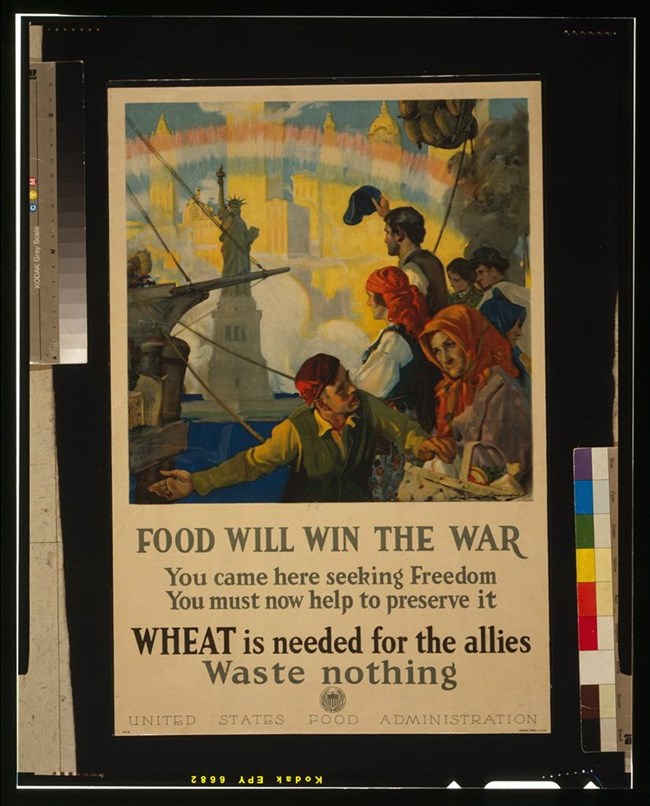

The First World War brought an end to one of the biggest periods of immigration in American history. During the decade leading up to the war, an average of 1 million immigrants per year arrived in the United States, with about three-quarters of them entering through the Ellis Island immigration station in New York Harbor. The United States up to this point had an “open door” immigration policy, with no limit on the number of people who could enter the United States. Those arriving simply had to pass a medical and legal inspection to show that they would not pose a danger or burden to their new country — and 98% of those arriving at Ellis Island passed.

While many Americans appreciated the contributions immigrants made to the labor force and did not feel threatened by ethnic diversity, others were not happy about the large numbers of foreigners arriving on U.S. shores. The precursors to World War I led to an increase in immigration from some regions of Europe. Refugees from Bulgaria, Greece, Romania, Serbia, and Turkey fled the Balkan Wars; Russians fled the unrest that would culminate in the Russian Revolution; and Jews fled for their lives from anti-Semitic pogroms throughout eastern Europe. Others chose to emigrate because they feared the long mandatory military service that many European countries required of their male citizens.

With the outbreak of the First World War, transatlantic steamship travel became more limited and dangerous, even as additional refugees sought to escape the conflict. British, French, German, and Italian liners that had previously carried masses of immigrants were converted to wartime use as troop and cargo transports and as hospital ships. Those steamships that remained in commercial operation were threatened by the rise of submarine warfare, as German officials felt justified in attacking ships that might be transporting military supplies to Britain and France, such as the attack on the RMS Lusitania in 1915.

Immigration to the United States slowed to a trickle because of the war, down to a low of 110,618 people in 1918, from an average of nearly 1 million. Those immigrants who did arrive in the United States faced difficulties beyond just the risks of travel. Some people found themselves stuck in a kind of limbo when they failed to pass inspection upon arriving in the United States, but were unable to be sent back to their homelands because of the war. So many found themselves in this situation that immigration officials had to develop parole procedures so that such individuals would not have to be detained in federal facilities for the duration of the war.

Anti-immigrant sentiments in the United States were strengthened by the First World War, despite the fact that large numbers of immigrants served honorably in the U.S. armed forces. Stories of atrocities by German soldiers, both real and exaggerated, fed hostility toward persons of German descent and led many immigrants to hide their heritage. Irish immigrants also became suspect, because some Irish nationalists supported the German side in hopes that a British defeat would result in Ireland’s independence. Russian immigrants were feared as possible anarchists and communists, as the “Red Scare” took hold with the onset of the Russian Revolution.

Growing isolationist and nativist sentiments in the United States would eventually lead to the closing of America’s “golden door” following the end of the First World War.