Last updated: November 5, 2023

Article

History Under Construction

NPS/ Jace Ritchey

The facts are not “under construction,” but the way we tell history is.

When you think of history and how it is often taught, what concepts come to mind? In reflecting on this question with rangers, visitors to Muir Woods have often described history as static, definitive, and of a singular perspective. Our concept of the past reflects personal biases – the information we have learned and had affirmed through life experiences. History has typically been presented from the perspective of the dominant group in power and can, intentionally or not, exclude details that tell a more holistic story.

As park rangers, we are always learning about the sites we preserve. Our mission extends beyond recreation – the work we do is “for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations.” Research can unveil new information that challenges the conclusions we were previously confident in. We do active “construction” on the exhibits in the park, employing rigorous reevaluation to ensure they reflect up-to-date information and research. This reflective process is critical to understanding both our history and future; we invite you to apply this work in your own life, classroom, and community. While the facts or building blocks of history remain much the same over time, our perceptions of the past are constantly "under construction."

Who chooses how history is told?

There are many reasons why specific narratives aren’t shared. Sometimes, those telling the stories fail to consider perspectives outside their own. For example, the NPS employed few women and even fewer people of color from its founding in 1916 through the early 1960s. Unsurprisingly, early stories we shared reflect the biased perspective of a predominantly white, male workforce. As more people from different backgrounds became able to join the park service, their perspectives enriched the diversity of stories we share. For example, the research on women’s history at Muir Woods began in earnest in 2018 when a ranger asked herself, “was anyone else involved in this story?” Her findings laid the groundwork for our project researching how how women saved Muir Woods.

Other times, narratives challenge the way we see the world. This helps us expand our ideas about power, science, gender, race, and more.

For example, one of the most prominent figures in the founding of Muir Woods is William Kent. In the past, we shared a story of an uncomplicated champion of conservation. After all, he protected Muir Woods by donating it to the federal government. He also authored the legislation that established the National Park Service. However, this legacy is incomplete. During his public speeches running for Congress, he said, “We must exclude Asiatics... I wish it were possible to ship them all away.” In office, he pushed through policies that barred Asian immigrants from entering the country, owning land, and becoming US citizens. While he mobilized around preserving National Parks, he had a limited view of who should be welcome to experience them.

Another example comes in the connection between the eugenics movement and redwood conservation. Eugenicists believe that society should prevent some groups of people from having children. Most often, those targeted were people of color, those with disabilities, and members of lower classes. Not all early redwood conservationists supported the eugenics movement, but many of them did. Madison Grant and Theodore Roosevelt are two notable redwood conservationists with ties to the eugenics movement.

The role of the National Park Service is to preserve history - the good, the bad, the ugly, and everything in between. It’s not our job to judge what history is worth telling, but to share an accurate and comprehensive history.

When visiting a redwood forest, most are humbled by the towering trees. But to eugenicists, a redwood’s unique resilience to pests, fire, and insects, and its reproductive strength were metaphors for White supremacy. In their world view, two ‘supreme species’ were struggling. They felt the “Nordic race” was making their last stand against “the invading hordes of immigrants.” At the same time, redwoods were making their “last stand” against the “invading hordes of loggers and developers” (Defending the Master Race page 272).

This belief of redwoods as a superior species can be found throughout redwood preservation history. In fact, one of the early drafts for signage about redwoods at Muir Woods asks, "how can their great height be explained?... A superior race?"

While many believed that redwoods trees stood alone and were superior to other species, we now understand that species within an ecosystem must work together to thrive. The ecology of Muir Woods exemplifies this: redwoods exist within a complex and interdependent web of organisms that together make up the forest.

At Muir Woods, we found several stories were largely missing from our signage.

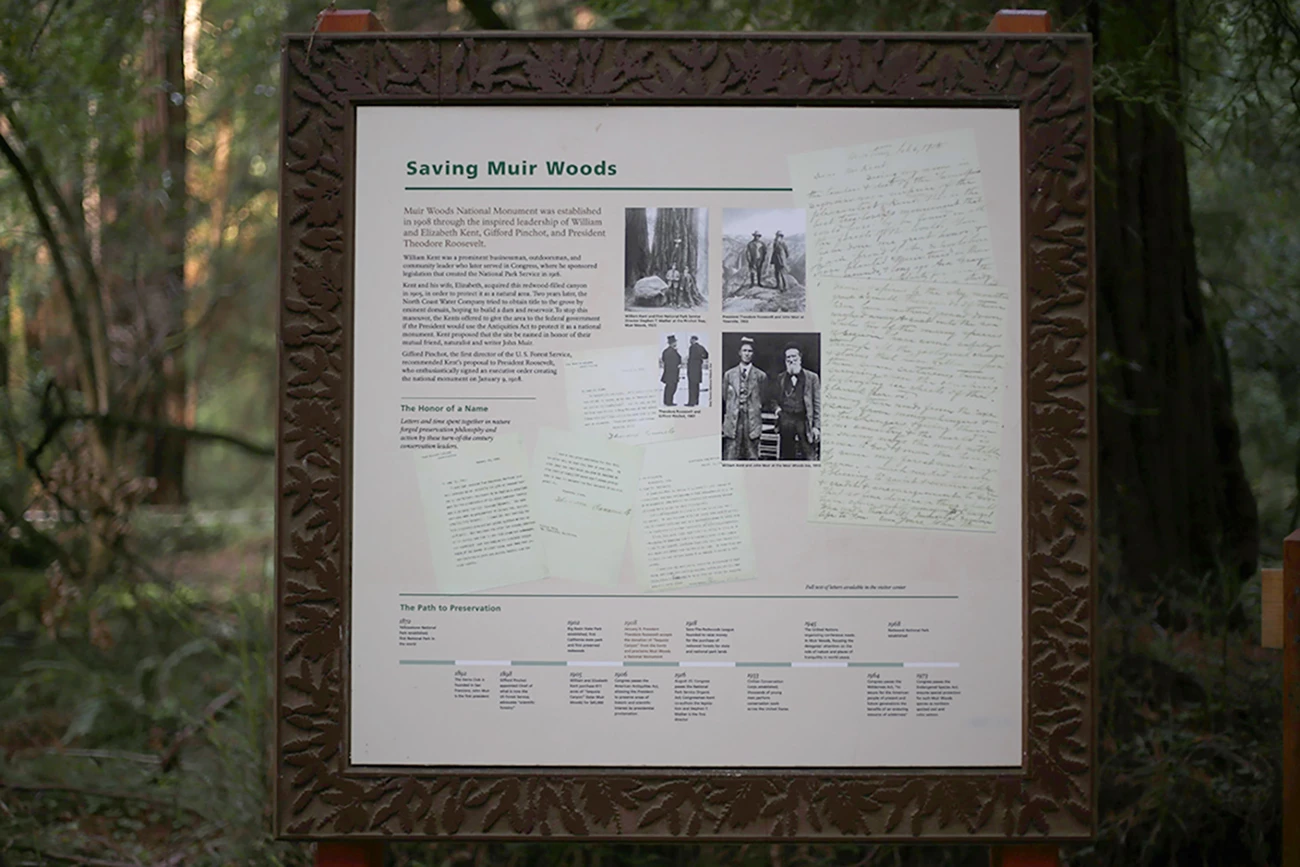

In Founder’s Grove, we have a sign called “Saving Muir Woods.”. It explains how John Muir, President Theodore Roosevelt, William Kent, and Gifford Pinchot helped save this forest.

On the bottom of the sign, there is a timeline of specific dates important to the Muir Woods story. Until being updated, its first date was in 1872, when Yellowstone National Park was established as the first National Park in the United States. The final date on the timeline was in 1973, when Congress passed the Endangered Species Act that protected species in Muir Woods like the northern spotted owl.

None of those dates or information were wrong. But they didn’t tell the full story.

It left out Indigenous stewardship, which started thousands of years before the first date on the original timeline. There was also no explanation of why Indigenous Peoples were no longer in their ancestral homes. There was no mention of the women who were crititical to saving Muir Woods. Similarly absent was an honest look at the complex legacies of some of the park’s founders. So much important historical context was missing from our sign that, it was inaccurate by omission.

How do we share more complete histories?

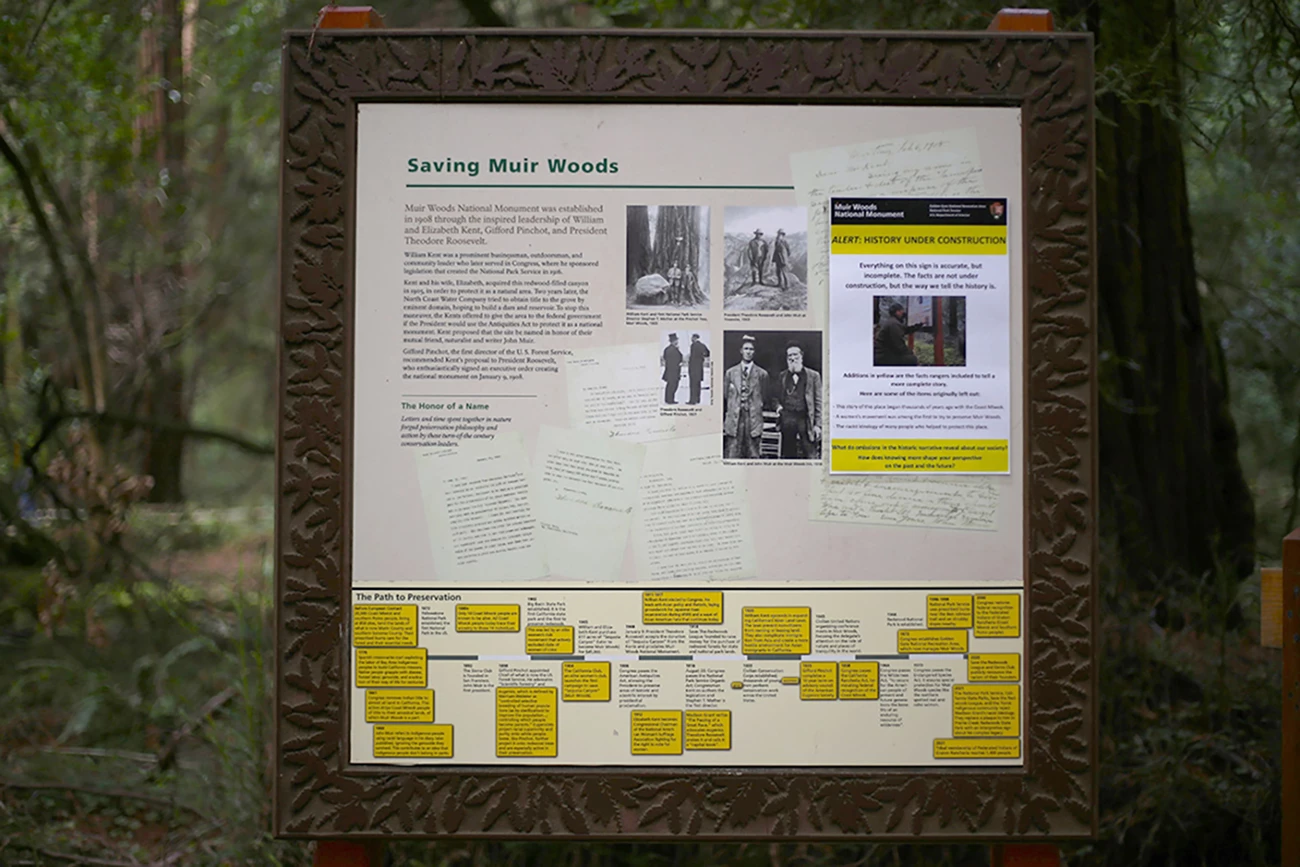

Left image

The text in white was featured on the original timeline. Everything in yellow is the information we added.

Right image

Credit: NPS/ Jace Ritchey

To call attention to the stories that have been previously missing, we put up a new sign saying “Alert! History Under Construction!” Importantly, no dates from the original timeline were removed or modified. Rather, we added the context needed to tell a complete story.

When you explore the differences between the two colors, what stands out? What surprises you about what was originally there, and what was missing?

The process of revisiting timelines is a powerful way to critically ask what is absent from the story and why is it missing. As we examine the answers to these questions, we can start to understand how the stories we tell reflect who we are as a society.

Reflecting on this, rangers recognized it was important to share findings with the public. After all, we strive to create transformative experiences that examine the values and principles of American and global societies as a way for individuals to examine their own beliefs. With this project, we committed ourselves to that.

What histories in your community are incomplete or inaccurate? What can you do about it?

From redwood conservation to the legacy of the country's founders, American stories are enriched by complexity, dimension, and challenge. It’s not our job to judge these stories or promote a singular narrative. As national park rangers, it is our mandate to tell complete stories that reflect who we are as a society. And as Americans, it’s important that we hear them.

Further Reading & Resources

- Reframing History: a toolkit for educators from FrameWorks Institute

- History, the Past, and Public Culture: Results from a National Survey from the American Historical Association

- Imperiled Promise: a report on the state of history in the National Park Service by the Organization of American Historians

- Area History from Redwood State and National Parks

Timeline

The following details the timeline reflected on the "Saving Muir Woods" sign. Text bold & underlined is what was on the original timeline; any regular text was added during the History Under Construction revisions.

Before European Contact 20,000 Coast Miwok and Southern Pomo people, living at 850 sites, tend the lands of what is now Marin County and southern Sonoma County. Their prescribed burns care for the forest and their essential needs.

1776 Spanish missionaries start exploiting the labor of Bay Area Indigenous peoples to build California missions. Native people grapple with disease, forced labor, genocide, and eradication of their way of life for centuries.

1861 Congress removes Indian title to almost all land in California. This action strips Coast Miwok people of title to their ancestral lands, of which Muir Woods is a part.

1869 John Muir refers to Indigenous people using racist language in his diary, ignoring the genocide they survived. The diary is published in 1911.

1872 Yellowstone National Park established; the first National Park in the US.

1880s Only 14 Coast Miwok people are known to be alive. All Coast Miwok people today trace their ancestry to those 14 individuals.

1892 The Sierra Club is founded in San Francisco, John Muir is the first president.

1898 Gifford Pinchot appointed Chief of what is now the US Forest Service, he advocates “Scientific forestry” and eugenics, which is defined by Merriam-Webster as “controlled selective breeding of human populations (as by sterilization) to improve the population...; controlling which people become parents.” Eugenicists project racial superiority and purity onto white people. Some, like Pinchot, further project it onto redwood trees and are especially active in their preservation.

1902 Big Basin State Park established; it is the first California state park and the first to preserve redwoods. This was led by an elite women’s club movement that actively excluded clubs of women of color. 1904 The California Club, an elite women’s club, launches the first campaign to save “Sequoia Canyon” (Muir Woods).

1904 The California Club, an elite women’s club, launches the first campaign to save “Sequoia Canyon” (Muir Woods).

1905 William and Elizabeth Kent purchase 611 acres of “Sequoia Canyon” (later to become Muir Woods) for $45,000.

1906 Congress passes the American Antiquities Act, allowing the President to preserve areas of historic and scientific interest by presidential proclamation.

1908 January 9: President Theodore Roosevelt accepts the donation of “Sequoia Canyon” from the Kents and proclaims Muir Woods National Monument.

1911-1917 William Kent elected to Congress. He leads anti-Asian policy and rhetoric, laying groundwork for Japanese mass incarceration during WWII and a wave of Asian American hate that continues today.

1912 Elizabeth Kent becomes Congressional Chairman of the National American Woman’s Suffrage Association fighting for the right to vote for women.

1916 August 25: Congress passes the National Park Service Organic Act; Congressman Kent co-authors the legislation and Stephen T. Mather is the first director. Madison Grant writes “The Passing of a Great Race”, advocating eugenics. Theodore Roosevelt praises it and calls it “[a] capital book”.

1918 Save-The-Redwoods League founded to raise money for the purchase of redwood forests for state and national park lands.

1920 William Kent succeeds in expanding California’s Alien Land Laws. The laws prevent non-citizens from owning or leasing land. They also complicate immigration from Asia and create a more hostile environment for Asian immigrants in California.

1933 Civilian Conservation Corps established; thousands of young women and men perform conservation work across the United States.

1935 Gifford Pinchot completes a 10-year term on advisory council of the American Eugenics Society.

1945 Civilian United Nations organizing conference meets in Muir Woods, focusing the delegate’s attention on the role of nature and places of tranquility in the world.

1958 Congress passes the California Rancheria Act, terminating federal recognition of the Coast Miwok.

1964 Congress passes the Wilderness Act, “to secure for the American people of present and future generations the benefits of an enduring resource of wilderness.”

1968 Redwood National Park is established.

1972 Congress establishes Golden Gate National Recreation Area, under which Muir Woods is now managed.

1973 Congress passes the Endangered Species Act; It ensures special protection for such Muir Woods species as northern spotted owl and coho salmon.

1996-1998 National Park Service uses prescribed burns near the Ben Johnson trail and on shrubby slopes nearby.

2000 Congress restores federal recognition to the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria (Coast Miwok and Southern Pomo people).

2020 Save the Redwoods League and Sierra Club publicly renounce the racism of their founders.

2021 The National Park Service, California State Parks, Save the Redwoods League, and the Yurok Indigenous community reject Madison Grant’s racist ideology. They replace a plaque to him in Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park with an interpretive sign about his complex legacy.

Tribal membership of Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria reaches 1,400 people.