Neither the Federalists nor the Republicans accepted the legitimacy of the other party. Both cast their opponents as a selfish and destructive faction bent on perverting the fragile republic. Ironically, that dread of parties drove each group to practice an especially bitter partisanship. Claiming exclusively to speak for the people, each party cast rivals as insidious conspirators bent on destroying freedom and the union.

Both the Federalists and the Republicans favored preserving American neutrality in the global conflict, but each group accused the other of covertly undermining that neutrality.

Differences in Opinion

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

As the more conservative party, the Federalists sought greater social stability and national power—at the expense of the states. During the 1790s, the Federalists established a national bank, consolidated a national debt, built an army and navy, and funded their expensive initiatives with increased taxes. The Federalists agreed with Britons that a true nation needed a central authority invested with the power to act with energy.

The Republicans favored a minimal federal government and a decentralized union, where most power remained with the states. They insisted that dispersing power would prevent the emergence of an American aristocracy to dominate a national government. Equality and consent, not central command, should unite the people. Of course, Federalists rejected the Republican vision as dangerously naive and doomed to collapse into anarchy.

The Republicans and Federalists also clashed over the proper degree of democracy needed to sustain the national republic. The Federalists insisted that common people should elect, and then defer to, a paternalistic elite defined by their superior education, wealth, and status. Once elected, gentlemen should govern free from “licentious” criticism that eroded public esteem for them. In sharp contrast, the Republicans promised to heed public opinion and to deny special privileges to any elite. They insisted that equal rights and opportunity would elevate the industrious poor rather than perpetuate the idle rich.

But, while pushing for equal rights for white men, most Republicans disdained Indians and African Americans. In their racial hierarchy, all white men were equal in their rights and superior to all blacks and natives. By comparison, the more elitist Federalists treated Indians and blacks as worthy of some paternalism and protection. To appeal for white votes, the Republicans derided the Federalists as pro-black and pro-Indian.

In the Shadow of Revolution

The National Map USGS

The French Revolution reignited the debate among Americans over the proper meaning of their own still unsettled revolution. The Republicans identified with France as a sister republic assailed by the monarchies of Europe, but the Federalists denounced the French Revolution as dangerously radical and violent. Both the Federalists and the Republicans favored preserving American neutrality in the global conflict, but each group accused the other of covertly undermining that neutrality. The Republicans feared that a British triumph would embolden the Federalists to undermine the republican institutions in America. The Federalists similarly dreaded that a French victory would unleash a new and more radical revolution within the United States. Both parties exaggerated the danger posed by the other. In fact, the Republicans were not French-style radicals, and the Federalists were not aristocratic loyalists. But both parties acted on their lurid fears rather than on a dispassionate examination of the facts.

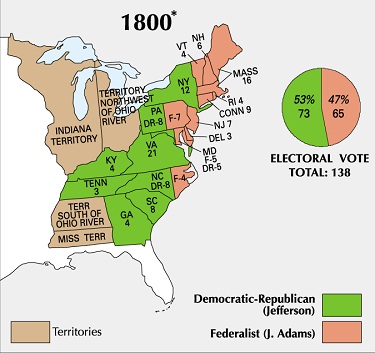

In the election of 1800–1801, the Republicans swept the Federalists from national power. Jefferson became president and worked to weaken the federal government and to empower the states. He cut taxes, reduced the military, and paid down the national debt. Jefferson also ousted free blacks from federal jobs and accelerated the dispossession of Indians. Sidelined, the Federalists seethed and longed for an opportunity to return to power—but in 1808 the Republicans elected Madison to succeed his friend Jefferson as president.

Part of a series of articles titled From the American Revolution to the War of 1812 .

Last updated: March 6, 2015