Last updated: August 28, 2024

Article

Hazel Ying Lee

U.S. Air Force photo illustration/John Turner.

Hazel Ying Lee was one of the first Chinese American women to earn her pilot’s license and the first to fly for the United States military. During World War II, Lee served with the Women Air Force Service Pilots (WASP). She and Margaret “Maggie” Gee were the only two Chinese Americans to serve as WASP.[1] At the time, the military did not allow women pilots to fly in combat or overseas. But in the WASP, they could ferry planes between military bases, perform test flights, and even run training exercises for combat pilots.[2]

Lee’s journey to the skies was not always free of turbulence. During the early 1900s, it was uncommon for women to become aviators. Lee experienced discrimination because of her race and gender. Despite these barriers, she became one of 1,072 highly trained and skilled WASP.[3] Even within this small group, Lee made a difference. When Lee died on November 25, 1944, she became the last of 38 WASP who died in service.[4] But her life was more than just a series of statistics.

US Air Force photo/Maj. Alysia R. Harvey.

The Dream

Lee was born in Portland, Oregon to immigrant parents on August 24, 1912.[5] Her father left China to escape the conflict between the Nationalists and Communists. Even though the Chinese Exclusion Act was still in force, her father found his way to the U.S. When he arrived in Oregon, he met Hazel’s mother. They married and had eight children.[6]

Even as a teenager, Lee wanted to take to the skies. After graduating from high school, she got a job as an elevator operator to pay for flying lessons.[7] Lee eventually entered a flight program sponsored by the Portland Chinese Benevolent Society. Through the Society, she also received financial support from the local Chinese community.[8] By October 1932, Lee graduated with her pilot’s license. Although she was only 20 years old, she was already a talented pilot.

Persistence

Around the same time that Lee earned her pilot’s license in 1932, the Empire of Japan launched an invasion into Manchuria, a region in northeast China.[9] Like many other Chinese Americans, Lee was outraged. She traveled to China in 1933, hoping to enlist in the Chinese Air Force to help defend the country.[10] Despite her enthusiasm and training as a pilot, the Chinese military turned Lee away because she was a woman.

Although she could not enlist in the Chinese Air Force, Lee was still concerned about China’s future and determined to fly. For a few years, she remained in China. Lee worked an office job for the military and taught at a school in her father’s hometown.[11] When she could, she flew commercial freight flights.

Over the next few years, the conflict with Japan only intensified. When the Japanese invaded China in 1937, Lee tried to enter the Chinese Air Force again. But the military still refused to accept women as pilots. Although she was rebuffed by the military twice, Lee was determined to act. While living in Canton, she helped her friends find shelter after Japanese air attacks.[12]

In 1938, Lee returned to the United States as an employee for the Chinese government. Because she was fluent in both Chinese and English and knew what was going on in China, the Chinese government hired her to buy war materials in New York.[13] Although Lee was happy to support the military in this role, she still had bigger dreams to fly.

Photo by Lois Hailey.

WASP Service

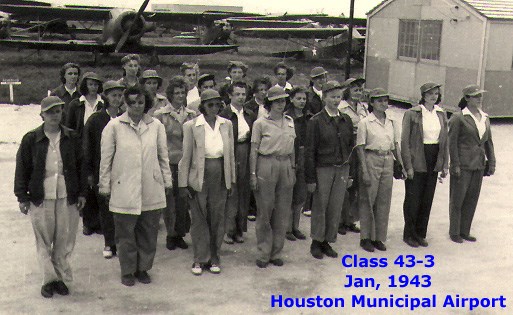

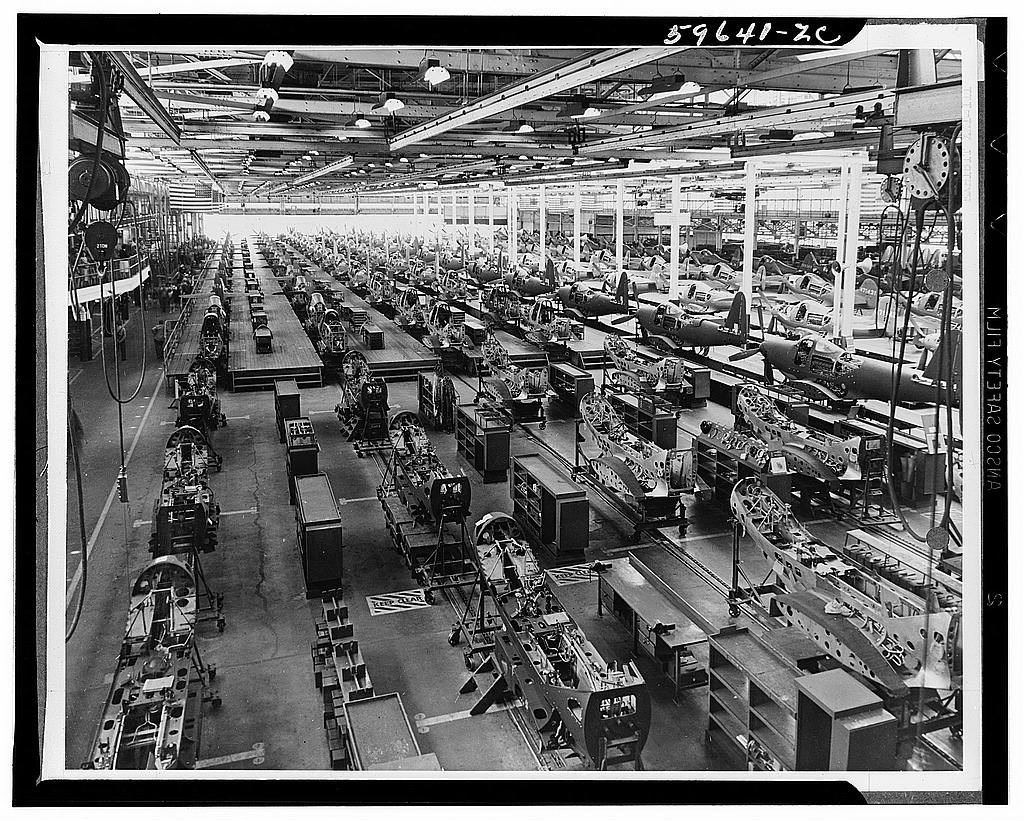

In the fall of 1943, Lee applied for the Women’s Flying Training Detachment (WFTD) of the United States Army Air Forces.[14] The WFTD was a rigorous, non-combat training program that prepared women pilots to fly military aircraft. In August 1943, WFTD merged with the Women Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron to form the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP).[15] As part of the WASP, Lee’s job was to deliver aircraft from American factories—often converted automobile plants—to military bases where they would be shipped to the European and Pacific fronts of the war.[16] The WASP’s ferrying and transportation services played a key role in the war effort. Hiring civilian women to perform these tasks enabled more male pilots to serve in combat.[17]

In February 1943, Lee began six months of intensive WASP training at Avenger Field in Sweetwater, Texas.[18] New WASP participated in thirty weeks of flight training and attended 560 hours of ground school classes.[19] In addition to proving their skill as pilots, the WASP had to overcome gender discrimination. Some male pilots were resentful and did not believe women were qualified to fly the same planes as men. They questioned women’s physical strength and emotional stability.[20] Additionally, the WASP received lower pay than their male counterparts and had to pay for their own living expenses and uniforms.[21] Some pilots even forced the WASP to perform undesirable missions—such as flying aircraft with open cockpits.[22]

US Air Force photo.

During her training, Lee became well known for her fearlessness, humor, and skill as a pilot. She taught her fellow predominantly white WASP about Chinese food and culture. Using lipstick, she wrote their names in Chinese characters on the sides of their planes.[23]

In October 1943, Lee married her fellow pilot “Clifford” Louie Yim-qun (also known as Louie Yen-chung). Because Cliff was a major in the Chinese Air Force, the couple spent long periods of time away from each other.[24]

After Lee completed her training, the WASP stationed her at Air Transport Command’s 3rd Ferrying Squadron at Romulus Army Air Base in Michigan. She piloted military planes of all shapes, sizes, and functions for ferrying and administrative flights.[25] Some of these aircraft included Boeing-Stearman PT-17 biplanes and single-engine North American T-6 Texans. Lee also flew larger transport aircraft, such as Boeing C-47s which could hold up to 6,000 pounds of cargo.[26]

US Air Force photo.

Taking Risks

Although female pilots were not cleared for combat, WASP missions could be dangerous. At first, WASP’s duties only involved ferrying aircraft used to train combat pilots or unarmed liaison aircraft, used for observation and transporting officers.[27] But as time went on, the WASP took on additional duties, including mock missions and cargo runs.[28]

Lee was always ready for a new challenge. In 1944, she attended the Pursuit School in Brownsville, Texas. She trained to become one of 134 total WASP qualified to pilot high-powered, single-engine fighters.[29] Planes of this class included the North American P-51 Mustang, Bell P-63 Kingcobra, and Bell P-39 Airacobra.[30]

Some pilots learned how to tow targets at Camp Davis, North Carolina. Learning how to fly while towing a target was physically taxing and strained both the plane and the pilot.[31] This duty involved attaching a long piece of fabric to the back of the plane with a towline. When the plane took off, the fabric trailed behind it, providing the perfect target for anti-aircraft gunner practice.[32] Women pilots also proved their mettle by performing test flights with aircraft to make sure they would be safe for male pilots to fly.[33]

Despite these daunting and dangerous situations, Lee was well known for her skill in the cockpit. Her flying career only involved two forced landings, including in a farmer’s field in Kansas. The farmer mistook Lee for a Japanese operative. He terrorized her with a pitchfork until she could convince him that she was an American.[34]

Final Flight

Office of War Information, Overseas Picture Division, collections of the Library of Congress.

On November 10, 1944, Lee embarked on a mission to the main Bell Aircraft factory near Niagara Falls, New York. Her mission was to transport a brand-new P-63 Kingcobra fighter plane to Great Falls, Montana. Lee’s destination was part of the Alaska-Siberia Lend Lease Route, a supply chain to get American-made aircraft to the Allied Forces in the Soviet Union. Over the course of the war, Lee and other Pursuit pilots delivered over 5,000 fighters to Great Falls. Male pilots then flew the planes to Alaska, where the Soviets would take over.[35]

Bad weather disrupted and delayed the mission. When the weather finally cleared, Lee took off from Fargo, North Dakota on Thanksgiving morning, November 23. On her approach, she received the all-clear to land at Great Falls. At the same time, several other P-63s approached the airfield to land, confusing the control tower operators. Immediately after Lee successfully landed, her plane collided with another P-63. First responders pulled Lee from the blazing wreckage and rushed her to a hospital. Lee sustained serious burns and died two days later, on November 25, 1944.[36]

Reverse design by the US Mint.

Because the WASP were considered civilians, they and their families did not receive any military benefits. The United States Army Air Forces refused to pay for the WASP’s funerals, even if they died in service.[37] In 1944, Congress introduced legislation to grant the WASP veteran status, but it failed after male pilots opposed the bill. Congress did not successfully grant the WASP veteran status and military benefits until over 30 years later.[38] In 2010, Congress also awarded the WASP the Congressional Gold Medal, one of the highest civilian honors in the United States.[39]

[1] K. Scott Wong, Americans First: Chinese Americans and the Second World War (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2005), 55.

[2] Kathleen Cornelsen, “Women Airforce Service Pilots of World War II: Exploring Military Aviation, Encountering Discrimination, and Exchanging Traditional Roles in Service to America,” Journal of Women’s History 17, no. 4 (2005): 112.

[3] Deborah G. Douglas, “Nieces of Uncle Sam: The Women’s Airforce Service Pilots,” American Women and Flight since 1940, assisted by Amy E. Foster, Alan D. Meyer, and Lucy B. Young (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2004), 98.

[4] Alan Rosenberg, “For Her Countries, Both,” Aviation for Women, November/December 2010, 33, http://www.afwdigital.org/afw/20101112/?pg=34#pg34.

[5] Heather Burmeister, “Hazel Ying Lee (1912-1944),” Oregon Encyclopedia, last updated January 22, 2021, https://www.oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/lee_hazel_ying/#.YItszbVKg2x.

[6] Wong, Americans First, 55.

[7] Burmeister, “Hazel Ying Lee.”

[8] Wong, Americans First, 55.

[9] Burmeister, “Hazel Ying Lee.”

[10] Rosenberg, “For Her Countries,” 32.

[11] Wong, Americans First, 56; Burmeister, “Hazel Ying Lee.”

[12] Rosenberg, “For Her Countries,” 32.

[13] Rosenberg, “For Her Countries,” 32.

[14] Douglas, “Nieces of Uncle Sam,” 92.

[15] Cornelsen, “Women Airforce Service Pilots,” 112.

[16] Rosenberg, “For Her Countries,” 32.

[17] Cornelsen, “Women Airforce Service Pilots,” 111.

[18] Burmeister, “Hazel Ying Lee.”

[19] Douglas, “Nieces of Uncle Sam,” 97.

[20] Cornelsen, “Women Airforce Service Pilots,” 115.

[21] Burmeister, “Hazel Ying Lee.”

[22] Rosenberg, “For Her Countries,” 32.

[23] Rosenberg, “For Her Countries,” 32.

[24] Katie Hafner, “Overlooked No More: When Hazel Ying Lee and Maggie Gee Soared the Skies,” New York Times, last updated May 26, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/21/obituaries/hazel-ying-lee-and-maggie-gee-overlooked.html; Kali Martin, “Women Airforce Service Pilot Hazel Ying Lee,” The National World War II Museum, published May 24 2021, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/women-airforce-service-pilot-hazel-ying-lee.

[25] Burmeister, “Hazel Ying Lee.”

[26] Burmeister, “Hazel Ying Lee.”

[27] Douglas, “Nieces of Uncle Sam,” 99.

[28] Douglas, “Nieces of Uncle Sam,” 99.

[29] Burmeister, “Hazel Ying Lee.”

[30] Rosenberg, “For Her Countries,” 33.

[31] Cornelsen, “Women Airforce Service Pilots,” 111.

[32] Douglas, “Nieces of Uncle Sam,” 99.

[33] Cornelsen, “Women Airforce Service Pilots,” 112.

[34] Burmeister, “Hazel Ying Lee.”

[35] Rosenberg, “For Her Countries,” 33.

[36] Rosenberg, “For Her Countries,” 33.

[37] Burmeister, “Hazel Ying Lee.”

[38] Cornelsen, “Women Airforce Service Pilots,” 115.

[39] Burmeister, “Hazel Ying Lee.”

Burmeister, Heather. “Hazel Ying Lee (1912-1944).” Oregon Encyclopedia. Last updated January 22, 2021. https://www.oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/lee_hazel_ying/#.YItszbVKg2x.

Cornelsen, Kathleen. “Women Airforce Service Pilots of World War II: Exploring Military Aviation, Encountering Discrimination, and Exchanging Traditional Roles in Service to America.” Journal of Women’s History 17 no. 4 (2005): 111-119. Project MUSE. https://doi.org/10.1353/jowh.2005.0046.

Hafner, Katie. “Overlooked No More: When Hazel Ying Lee and Maggie Gee Soared the Skies.” New York Times. Last updated May 26, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/21/obituaries/hazel-ying-lee-and-maggie-gee-overlooked.html.

Douglas, Deborah G. “Nieces of Uncle Sam: The Women’s Airforce Service Pilots.” American Women and Flight since 1940. Assisted by Amy E. Foster, Alan D. Meyer, and Lucy B. Young. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2004.

Martin, Kali. “Women Airforce Service Pilot Hazel Ying Lee.” The National World War II Museum. Published May 24 2021. https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/women-airforce-service-pilot-hazel-ying-lee.

Rosenberg, Alan. “For Her Countries, Both.” Aviation for Women, November/December 2010.

http://www.afwdigital.org/afw/20101112/?pg=34#pg34.

Wong, K. Scott. Americans First: Chinese Americans and the Second World War. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2005.

Tags

- women in world war ii

- world war ii

- wwii

- world war ii home front

- wwii home front

- women in the military

- aviation

- aviation history

- women's history

- asian american and pacific islander history

- military and wartime history

- wasp

- texas

- us army

- women airforce service pilots

- aapi

- aapi heritage

- aapi history

- asian american

- asian american pacific islander