Last updated: January 25, 2018

Article

Harmonizing Paradise

NPS/R. Hui Photo 2016.

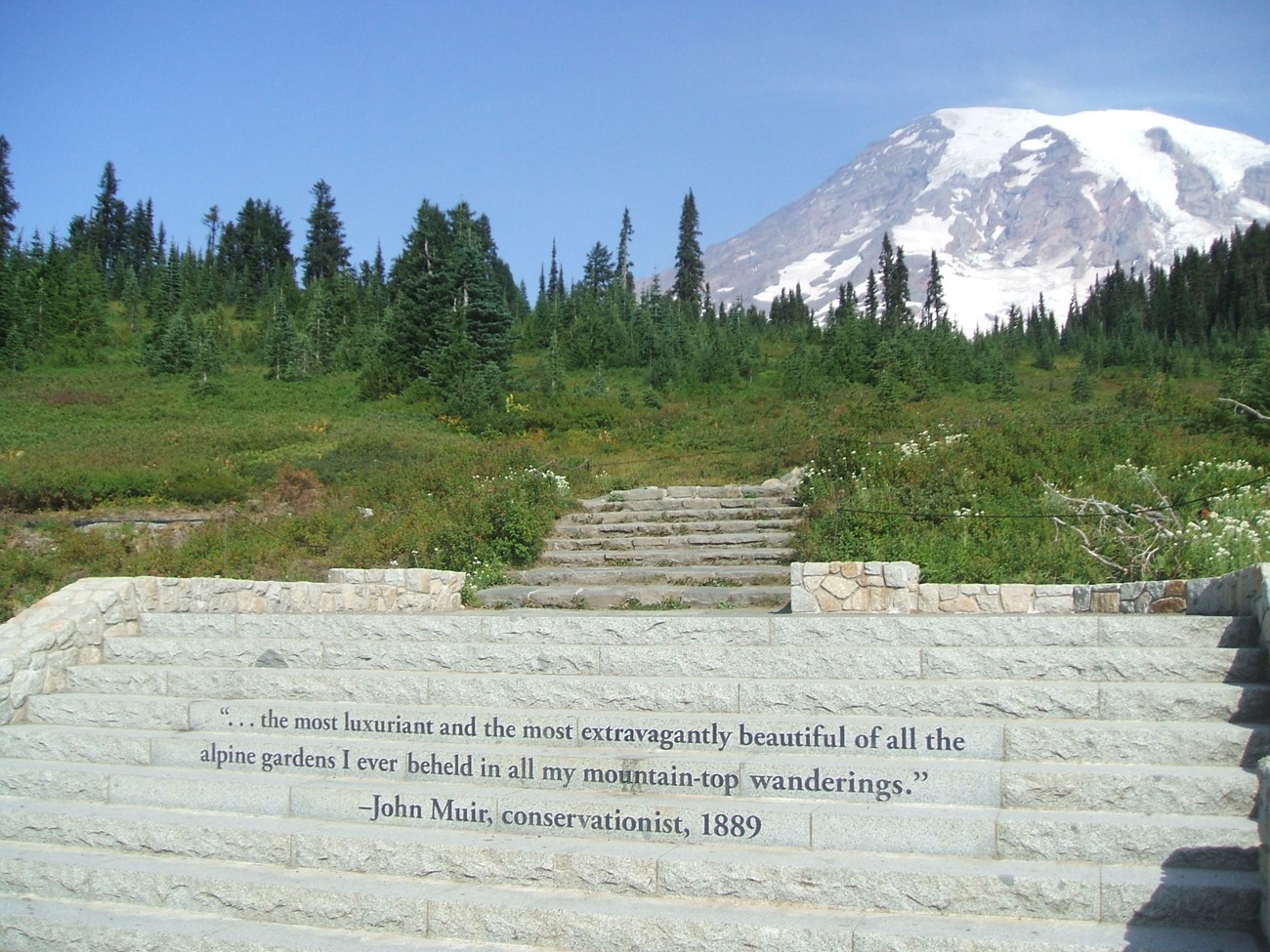

For many people, Paradise at Mount Rainier National Park means stunning, up-close views of the mountain, colorful subalpine meadows full of wildflowers, and amazing recreation opportunities. It’s a summertime utopia. But Paradise is more than wildflowers and mountain views, it’s also a heavily visited area with almost a million people a year dropping by to hike, photograph, and climb. Paradise is located over 5,000 feet up on a mountain with long, deep snowy winters. The stresses of so many people, such deep snow, and short summers etch themselves on the land and the buildings. For decades, rangers, volunteers, and staff have worked to balance the needs of visitors and the protection of the meadows and other natural resources. Bringing harmony to Paradise is still a work in progress today.

NPS/S. Redman Photo September, 2015.

Some of the first people to visit Paradise were members of local tribes like the Nisqually. Leaving behind some evidence from their stays, we know that people visited the area we now know as Paradise for at least the last 3,000 years and perhaps as long ago as 8,000 years. The rich resources of wildlife and plants enticed them to travel up from the river valleys to the high elevation subalpine meadows like Paradise. Here they could spend days and weeks during the summer gathering food and medicine and then return to the river valleys before winter struck.

The mountain also provided spiritual resources for those strong enough to climb its lofty heights. Stories from the Nisqually Tribe and other groups passed down knowledge of the summit and the lake hidden there. As Europeans and Americans entered the area, they too felt the pull to climb the mountain’s heights. Hazard Stevens and P.B. Van Trump with the help of their guide, Sluiskin, documented the first successful summit climb in 1870. Their base camp for the climb, where Sluiskin waited for the two men to return, was in Paradise near the top of Mazama Ridge. A monument marks the sight today.

NPS Photo 1915.

First mountain climbers, then campers made their way out to the slopes of Mount Rainier. Using the trail that James Longmire built from Ashford to Longmire and then up to Paradise, people found a rustic campground awaiting them as early 1895. John Reese started developing his Camp of the Clouds in 1898 with tents for guests and a dining tent on the shoulder of Alta Vista, just above where the Jackson Visitor Center stands today. Working with the U.S. Forest Service and then the National Park Service (NPS), Reese ran his camp in the summers, gradually expanding its size until 1916. The government constructed a rough road that reached Camp of the Clouds in 1910. Visitors were driving their cars up by 1912, creating a big increase in the number of people at Paradise.

NPS Photo

Folks wanted more lodging and food than the camp could provide so the Mount Rainier Park Company (MRPC) bought out Reese to expand the camping and started construction on the Paradise Inn and employee dorms. The Inn opened to guests in 1917, followed the next year by about 100 bungalow tents, the new Paradise Camp Lodge across the parking lot, and a new campground. The Paradise Camp Lodge would eventually expand to provide guest rooms but was originally built to provide food and supplies for the many campers.

Folks not only wanted to camp or stay at the lodge, they also wanted to climb Mount Rainier. The MRPC capitalized on these eager mountaineers by starting a guide service in 1915 and then built the Paradise Guide House for their guides, equipment, and lessons. As road and car access improved, more people felt the pull to climb Mount Rainier and in 1919, approximately 300 people summited the mountain. In 1921, about 500 people summited. Even with professional guides trained by Swiss alpinists, there were accidents and fatalities at times. In 1968, Rainier Mountaineering Inc took over guiding climbers and still used the Guide House in Paradise as their starting point. For many years, the most popular climbing route has started at Paradise: the Disappointment Cleaver route. Almost half of the folks climbing Mount Rainier today use this route. Nowadays, other companies also provide guide services, though some groups choose to climb independently. Over 5,400 people successfully summited Mount Rainier in 2017, but it still remains a very dangerous climb. Since record keeping began, over 120 people have lost their lives climbing the mountain.

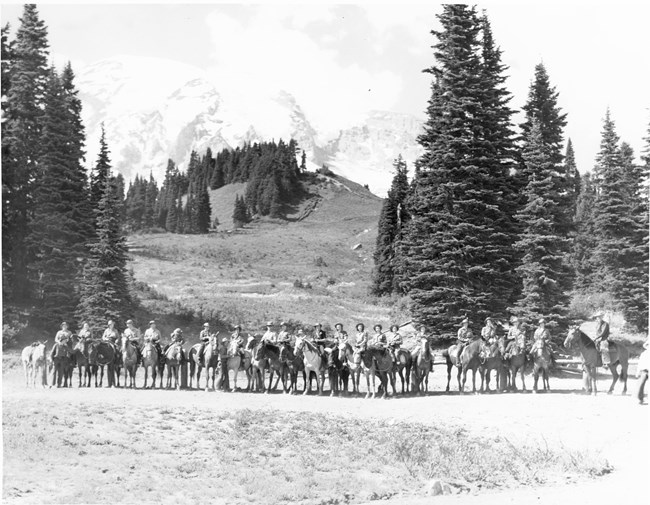

NPS Photo

For those folks who didn’t want to climb mountains, the MRPC provided guided hikes and horseback rides throughout the Paradise area. Horse corrals right beside the Guide House made it very convenient. The NPS also helped visitors with a park naturalist on staff to answer questions and guide hikes starting in 1924. This park ranger naturalist worked and lived in the new ranger station, built next to the Guide House in 1921.

When the road access improved in the 1910s and 1920s, a new hiker came to Paradise; the day hiker. You could drive to Paradise, hike for hours, and then drive back to Tacoma or Seattle in just one day. Paradise soon was swamped with these new day hikers. As early as the 1920s, people complained about the parking lots at Paradise filling up on nice days. In 1920, the National Park Service director wrote in a report that “the present parking space for automobiles at Paradise Valley is wholly inadequate for the needs at this point. Cars are parked all over the hillside at dangerous angles.” This issue continues today, but back then a full parking lot might have been 100 to 200 people and sunny summer days now can find thousands of people answering the siren call to visit Paradise.

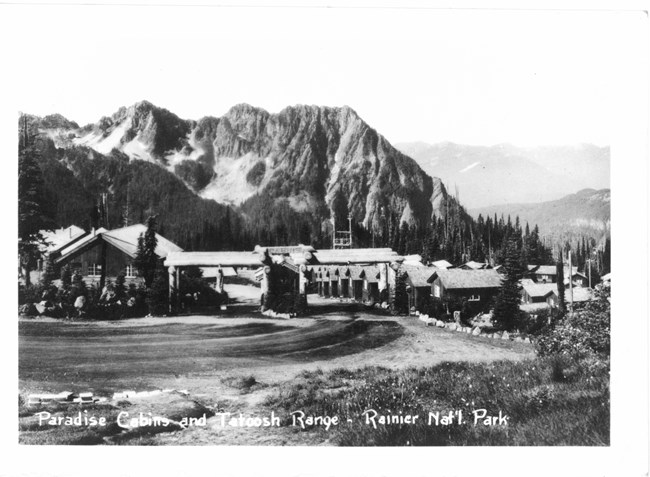

NPS Photo

By 1927,about 50,000 cars entered the park, bringing many visitors, guests, and campers to Paradise throughout the summer. More people required more facilities. Where the lower parking lot is today, a community building was constructed for campground ranger programs and activities. Camp of the Clouds closed in 1930, replaced by 275 cabins near the community building and then a new Paradise Lodge in 1931 in between the community building and cabins. The tents around the Paradise Inn had been removed when the Inn’s Annex opened in 1920 but with three lodges, the cabins and tent camping, there seemed to be enough accommodations to meet demand.

NPS Photo 1990.

The MRPC struggled maintaining all their buildings. The Great Depression and increasing use of automobiles, lowered the demand for overnight lodging. The long winters at Paradise meant most of these buildings were closed for much of the year, buried under heavy snow that stressed and strained the structures and requiring a lot of work and money to repair each summer.

The long and snowy winters, though damaging to buildings, also attract quite a number of skiers, snowshoers, and sledders. Back in the 1910s and 1920s, snow clearing equipment wasn’t nearly strong enough to keep the road open. The original road from Narada Falls to Inspiration Point, around Paradise Valley and up to the Paradise Inn, was allowed to close every winter due to snow. When the current two-lane road was built, it went through better terrain and less avalanche-prone areas. With better snow removal equipment, the National Park Service began keeping the road to Paradise open during the winter starting in 1930.

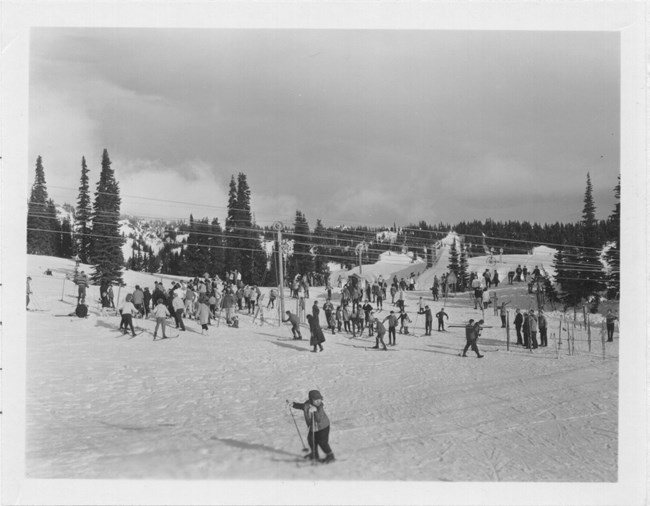

NPS/G. Peters January, 1964.

Winter-time access to Paradise brought more opportunities for winter recreation. Ski races and even Olympic tryouts were held in Paradise. The first tow rope was installed in 1938 to the top of Alta Vista. After World War II, returning soldiers with wartime ski training made downhill skiing very popular in the U.S. As demand for downhill skiing grew in the 1940s and 1950s, demand also grew to install more lifts and ski jumps at Paradise. Park managers had one firm rule; whatever was put up for the ski season had to be brought down before summer. After all, who wants to see a line of chairlift supports and cables running through their favorite meadow?

NPS Photo

As unsightly as the chairlifts would have been during the summer, some forms of recreation were actually damaging to the very natural resources the national park was created to protect. One form of recreation tried at Paradise was golf. A nine-hole golf course was etched into the Paradise Valley below the Paradise Inn. Because of the heavy snows, the course was only playable for two or three months a year and proved unprofitable for the MRPC. They let nature retake the course, but for decades the scars were visible. *pic of JVC1 possible snowy*

World War II took away the park’s visitors, some staff, and hit the budget hard. To scrape by, the MRPC sold the cabins which were moved down to the Seattle area to house defense industry workers. After the war, visitors returned in their cars. The road was much better quality now, allowing folks to visit Paradise for just a few hours instead of days. Buildings, already in states of disrepair, started to be demolished as they were not needed or replaced. The early employee dormitories near the Paradise Inn were gone, replaced by new ones in the lower parking lot. The Paradise Camp Lodge was torn down in the mid 1950s, while the 1960s saw the removal of the community building, Paradise Lodge, and campgrounds. But not all was lost. The Paradise Inn was renovated to help the building withstand fierce winters. A visitor center was constructed and opened in 1966 providing people with exhibits and information.

NPS/ Buehler 1987.

Over the years, the buildings at Paradise were not the only things to change. Early on, horses, cars, and people had meandered all over the meadows of Paradise, stepping on the very wildflower plants people enjoyed seeing. This trampling killed plants one footstep at a time, creating dustbowls where wildflowers had been. Folks noticed this and started working to protect Paradise. Horseback riding ended, as hooves can quickly tear up delicate plants and soils in the high elevations. Trails were rebuilt to handle heavy traffic. Social trails, ones made up by people walking off the designated trails, were closed off and then replanted to restore the wildflower meadows. Because of the long winters and short summers, restoring the meadows and growing new plants took many volunteers and many summers of work.

NPS Photo 2003.

Changes also came to winter activities at Paradise. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, downhill skiing grew in popularity in the U.S. and more folks from the Puget Sound wanted to drive up to Paradise to ski. As their demand for ski opportunities at Paradise peaked, a new answer arrived. The U.S. Forest Service began leasing land to downhill ski groups outside the park at Crystal Mountain and White Pass. There developers could build all the lifts, jumps and gondolas that downhill skiers demanded. Other winter activities replaced downhill skiing at Paradise. Cross-country and back-country skiing replaced downhill skiing. Instead of needing lifts and gondolas, these skiers would “skin up” hills under their own power and then ski down.

Sledding also became more popular too with one caveat; sleds do not tend to be steer-able. Over the years, sledding led to a number of injuries and even fatalities. Looking to make it safer, park staff took to building sledding runs surrounded by berms and called it the Snowplay Area. Today, its the only legal and safe location to sled in the park. Lately snowshoeing has also become more popular. To help novice snowshoers, park rangers guide snowshoe hikes from December through March, interpreting the wintery world of Paradise while teaching folks how to use these strange devices. On sunny winter, weekend days, it’s possible to find the parking lot at Paradise jammed with a couple hundred cars packed between the snow banks. What’s not possible to find any more are the rope tows and ski jumps. Downhill skiing at Paradise ended in the mid 1970s. You can find artifacts from these bygone recreational activities in the exhibits in the Jackson Visitor Center. If you look carefully, you can also find the old shed for the rope tow hidden between the restroom building and the Guide House. Look for the small “A”-frame building with its door on the second floor to deal with Paradise’s deep snow.

NPS Photo

Over the years, the first Jackson Visitor Center began to change as it showed the stress and strain of snowy Paradise winters. Built with a flat roof design, it required many gallons of diesel to heat the roof and melt the many feet of snow off. Designed and constructed before the Americans with Disabilities Act, the building didn’t meet modern accessibility needs. It had numerous other issues besides these and as the NPS looked at the aging building they knew something had to be done. The decision came about to build a new visitor center with a steep, alpine roof much like the Paradise Inn, Ranger Station, and Guide House. The new Jackson Visitor Center opened in 2008 and the old one was then torn down.

NPS/A. Spillane August, 2015.

Paradise, like the mountain it rests on, is a constantly changing place. Over the last hundred plus years, many people have visited this wonderous location. They enjoyed its beauty while placing demands on buildings and facilities. People need beauty and restrooms and food. When transportation was slow, lodging was a heavy requirement while today most people only stay for a few hours. Though many have rambled through the meadows, we also recognize the need to preserve those meadows for future visitors’ enjoyment. Its a balancing act; discerning and providing the things visitors need while protecting the land, plants, and animals that draw all these people. Is there harmony in Paradise?

For more information on the facilities, services and trails at Paradise, please click here.