Last updated: December 14, 2021

Article

Fort Vancouver as a Base for Missionary Efforts

NPS Photo

This article has been adapted from An Ethnohistorical Overview of Groups with Ties to Fort Vancouver, by Douglas Deur, Ph.D. The entire report can be read online here.

As a regional center of social, economic, and cultural exchanges, Fort Vancouver served as a stopover point for some of the earliest missionary efforts in the Pacific Northwest, and quickly grew into a missionary center of vast regional importance. If there were already many tribal communities represented at Fort Vancouver for purposes of trade and employment, missionaries’ efforts added immensely to the ethnolinguistic variety of the fort. The missions forged new or expanded links with a network of tribal communities expanding throughout the region, and fostered an almost continuous movement of tribal people between these communities and the fort.

Missionary accounts of the early years of Fort Vancouver abound, most alluding to brief stays at the fort while en route to other places within the region. A number of these early missionaries attempted to organize temporary congregations and preach to Fort Vancouver’s residents, who lived without a resident chaplain for many years. Most found the community’s cultural and linguistic diversity to be an imposing barrier to their success. While at Fort Vancouver in September of 1834, for example, missionary Jason Lee reported that he

“assayed to preach to a mixed congregation—English, French, Scotch, Irish, Indians, Americans, half breeds, Japanese, &c., some of whom did not understand 5 words of English. Found it extremely difficult to collect my thoughts or find language to express them but am thankful that I have been permitted to plead the cause of God on this side of the Rocky Mountains where the banners of Christ were never before unfurled” (Lee 1916: 399).

The challenges encountered and lessons learned by these early missionaries at Fort Vancouver contributed to their rapid adoption of the Fort’s interethnic lingua franca, Chinook Jargon (or ‘Chinuk wawa’) as their principal vehicle for communication with Indian communities beyond the fort. In time, prayers, catechisms, and other elements of church liturgy were translated into this language to foster their comprehension and dissemination within the Indian communities of the Northwest.

NPS Photo

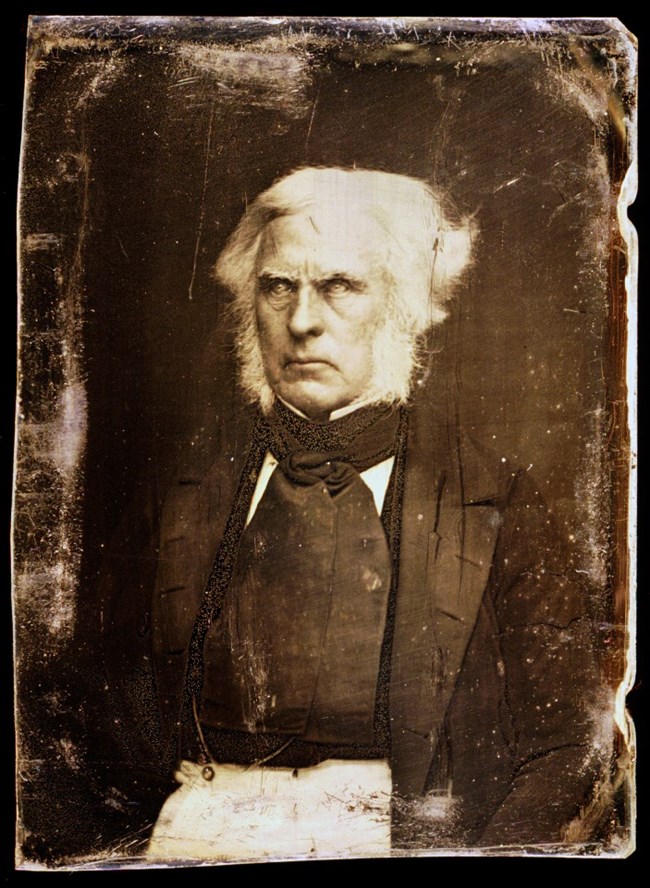

Herbert Beaver, Church of England

As these missionaries passed through Fort Vancouver, however, many complained to their home congregations, and sometimes to the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), regarding the absence of a resident chaplain at Fort Vancouver; rumors of licentiousness and Godlessness at the Fort were much overblown in these accounts, apparently to accentuate the need for reform. Under this pressure, HBC leadership - Chief Factor Dr. John McLoughlin among them - began to explore options for a clergyman to be stationed at the Fort. By 1836, the HBC assigned ordained Anglican priest, Herbert Beaver, to serve as the first chaplain to the Fort Vancouver community. Beaver, despite his surname, was a notoriously bad fit for a well-established fur trading community like Fort Vancouver. Arriving in September of 1836, Beaver was shocked by the conditions of frontier life. He was unabashedly bigoted and deeply contemptuous of the sizable portion of his congregation that were Indian or of Indian ancestry. Writing to Benjamin Harrison on March 10, 1837, Beaver said of his Indian congregation living at the Fort,

“it is impossible to conceive any descendants of that being, who was originally created in the image of God, to be sunk lower in the scale of humanity, of which, if I may so describe them, the[y] are the very excrement. Squalid and indolent, they would starve and go naked, both which they are frequently on the verge of doing, and would suffer famine and nakedness, were it not for the resources in the stores of the Company” (Beaver 1959: 40).

Racist and priggish, Beaver was clearly troubled by any marriages of non-Indian company employees to women who were not of pure European ancestry. Nonetheless, he doggedly pressured those employees who had engaged in “country marriages” or civil ceremonies, by choice or by frontier necessity, to remarry through Anglican religious ceremonies. He was noted for being “narrowly doctrinaire” during his slightly over two years in the role of Fort chaplain, being openly hostile toward the Roman Catholicism of the Francophone work force and making efforts, overtly and covertly, to convert the mixed-ethnicity schoolchildren to Anglicanism. He also began to petition the HBC to employ a meticulous moral and religious screening process to potential laborers before recruiting any more Native labor from Hawaii or other reaches of the HBC domain, so as to avoid importing “iniquity” to Northwestern shores. His scope of his reformist zeal was vast and ambitious.

McLoughlin himself became a focus of Beaver’s reform efforts. John McLoughlin refused Beaver’s requests that he and his wife, Marguerite, undergo a formal church wedding ceremony so as to set an example for the fort’s employees – in part due to his deep dissatisfaction with Beaver, Beaver’s protestant faith, and Beaver’s views of fur trade marriages. McLoughlin later came to blows with the reverend when Beaver denounced Marguerite McLoughlin in correspondence as a “female of notoriously loose character,” due to the fact that their marriage had not been sanctioned or sanctified by the church (though, a number of years later, John and Marguerite McLoughlin sought out the assistance of friend and colleague James Douglas to oversee a civil remarriage, in Douglas’ role as a Justice of the Peace) (Hussey 1991; Sampson 1973a: 124-26).

The Fort Vancouver community was largely unified in opposition to Beaver’s heavyhanded tactics, and he made few inroads into the social and religious life of his reluctant flock. Beaver was quick to place blame on the immorality and ignorance of the Fort residents. In his report to the Governor and Committee of the Hudson’s Bay Company, dated October 10, 1837, Herbert Beaver complained,

“It will thus be seen, that little improvement has taken place, since my arrival among them, in the religious state of my people, and I have with regret to observe, that as little in their moral, especially as regards the besetting sin of the community, is in progress. I have solemnized only one marriage between two persons of the lower order, the man being a Canadian, and the woman half-bred between an Iroquois and native woman; and although I have as yet no reason to suppose, that this will turn out otherwise than well, still, in the present deplorable and almost hopeless state of female vice and ignorance, I have no desire to unite more couples. If called upon to do so, I shall execute my office with reluctance, through the fear that the ceremony may be brought into contempt and disrepute by the woman’s subsequent misbehaviour, and thereby be rendered nugatory as to the beneficial consequences, of which the much wanted due observances of the marriage vow must in this infant Colony be productive” (Beaver 1959: 54).

Even after Beaver’s departure in 1838 - a move heartily supported by McLoughlin, HBC leadership, and presumably some large proportion of the resident Fort community - he continued a public campaign to condemn what he perceived as the vices of the Fort Vancouver community, to lobby for its aggressive reform, and to lament his ill treatment by the Fort leadership (Beaver 1959). In the end, Beaver’s reform efforts would prove largely unsuccessful, but would move the HBC to foster a new missionary effort, more compatible with the values, religious precedents, and ethnic admixture of the Fort Vancouver community.

NPS Photo

The Catholic Mission at Fort Vancouver

Within months of Beaver’s departure, Reverend F. N. Blanchet and Reverend Modeste Demers, of the Society of Jesus of the Roman Catholic Faith, established their mission at Fort Vancouver. They did so with the full moral and material support of HBC Governor and Committee. Leaving in the spring of 1838, Blanchet and Demers arrived at the Fort on November 24, 1838. Unlike Beaver, these men exhibited a degree of compassion and compatibility with the unique circumstances of the fur trading post; accordingly, Blanchet, Demers, de Smet, and other clergy tied to their Catholic mission were relatively well received in the Fort community. In the years that followed, they had profound effects on life both at the Fort and within the broad constellation of Indian communities with which it was connected (in Blanchet 1878). In addition to bolstering the Catholic influence among the Fort’s rank-and-file employees and providing regular services there, these missionaries used Fort Vancouver as a base of operations for the rapid expansion of Catholic missionary efforts throughout the Oregon Territory. Much as the HBC had utilized preexisting social and trade networks centered on the lower Columbia River to extend tendrils of commerce throughout the region and rapidly establish economic hegemony, so the Catholic church now used these same linkages to make quick inroads into native communities. As one protestant missionary later noted, the Fort was uniquely situated for church expansion efforts, a “centre from which divine light would shine out and illuminate this region of darkness” (Parker 1841: 170). Aligning itself with the HBC juggernaut, the Catholic mission had a considerable advantage over the handful of other missionaries, most of them protestant, who were attempting to establish themselves near some of the larger tribes of the Northwest. However, arriving so late in the history of the fort, Catholic missionary efforts played out within an ethnic geography already much transformed since the Fort’s original construction. While early traders may have reached out to a densely-settled Chinookan lower Columbia region, many of these communities were in rapid decline; instead, missionaries’ early efforts focused on those populations that had recently expanded along the lower Columbia – the Klickitat and Cowlitz – as well as surviving, largely Chinookan populations at those remaining major socioeconomic hubs as Willamette Falls, Clackamas, and the Dalles.

Initially, however, Blanchet and Demers – arriving without detailed knowledge of local tribes, local geography, or of Chinook Jargon – had no choice but to focus their efforts narrowly on the community at the Fort. In a letter from Demers to Reverend C.F. Cazeau, dated March 1st, 1839, he gave some indication of their slow start:

“I will give you an account of my ministry: For the last three months this Fort has, with the Canadians and Indians here, occupied all my time. I have found here some consolation; God has given me the grace to learn the Chinook language in a short time. It is in this jargon that I instruct the women and children of the white settlers, and the savages who come to see me from far and near. I am so busy from morning till night that I can scarcely find time to write the following concerning the savages who are settled on the west of the Rocky Mountains…” (in Blanchet 1878: 54-55).

Recognizing the urgency of using Chinook Jargon as the language of religious services and everyday communication, alike, Blanchet and Demers rapidly set to the task of translating their liturgy into the language:

“The Indians were not neglected; they were gathered twice a day, in the forenoon and in the evening. Rev. M. Demers, who had learned the Chinook Jargon in three or four weeks, was their teacher. Later in January, having translated the Sign of the Cross the Lord’s prayer and Hail Mary, into that idiom, he taught them to these poor Indians, who were much pleased to learn them. In February, he succeeded in composing some beautiful canticles in the same dialect which the Indians, as well as the men, women and children, chanted in the Church with the greatest delight. Thus by patience and constancy in teaching, the Missionaries were pleased to see that their hard labors were beginning to bear some fruits” (in Blanchet 1878: 67).

Cascade and Klickitat families appear to have been especially well represented at the Fort Vancouver mission services – at once reflecting their growing importance in and around the Fort community, while also demonstrating the mission’s influence in integrating these tribes into the larger social fabric of the Fort. Blanchet and Demers reported that these two groups “regularly attend catechism and evening prayer” at the Fort’s mission - services that these peoples readily comprehended due to their facility with Chinook Jargon. The missionaries began traveling with growing frequency to Cascade and Klickitat villages, reported to be a short distance away from the fort, and developed strong and enduring relationships with these communities (if official mission reports can be believed). Indeed, these communities were so close at hand that Blanchet and Demers could soon turn their attention to more distant populations, for these Cascade and Klickitat communities, although often seasonal, were not expected to fall out of missionary influence due to their sheer proximity. For example, Blanchet noted that, while some tribes might drift away from Catholic teachings to those of other denominations, “The Cascade Indians had a better chance, as their moving yearly, in October, on the left shore of the Columbia, nearly opposite Vancouver, brought them near to the priest” (in Blanchet 1878: 133).

Washington State Historical Society

Competition Among Missionaries

As the mission became established by the end of 1839, Blanchet and Demers began to make visits to the villages of those individuals from the lower Columbia region who had visited the Fort. They recognized that “many of the [lower] Chinook tribe had already seen the blackgown at fort Vancouver, and had had their children baptized; but they had not yet been visited in their own land”; on these grounds, Demers initiated a downriver trip from Fort Vancouver, seeking converts at Cowlitz and then at Fort George and elsewhere on the Columbia estuary (in Blanchet 1878: 114). They also arranged for a Catholic mission outpost to the Willamette Valley tribes and others near what is today St. Paul, Oregon. Still, it quickly became apparent to the missionaries that, if they were to be successful regionally, they would need to focus much of their attention on the large socioeconomic hubs of tribal life on the lower Columbia, including the Chinookan settlements at the Dalles and Willamette Falls. Worse yet, from their perspective, Methodist missionaries had already beaten them to these communities and were making inroads. As Blanchet reported,

“There were three Indian tribes which had been gained to Methodism for over a year, viz: those of Clackamas, Wallamette Fall, and Cascades. The two [Catholic] missionaries had been too busy to visit them before. A door was opened to them this year in the following manner: A chief of the Clackamas tribe called Poh poh, went to St. Paul in February; he saw there the orphan boys in charge of the Catholic mission, some Indian families and other persons, numbering over 15. He assisted at the daily exercises and explanation of the Catholic Ladder. He was a Methodist, and the Corypheus of the sect, but on looking at the Ladder and seeing the crooked road of Protestantism made by men in the 16th century, he at once, abjured Methodism, to embrace the straight road made by Jesus Christ; and returning home he invited the missionary to visit his tribe” (in Blanchet 1878: 119).

Reacting in response to this, the protestant missionaries in the region returned to Pohpoh’s village and others, initiating what became an intense competition for the ‘hearts and minds’ of particular large and influential settlements – especially the Clackamas and Willamette Falls settlements, as well as the settlements throughout the Portland Basin with which they were affiliated. Pohpoh’s allegiance was a frequently mentioned objective, apparently due to his regional prominence and influence, which seems to have extended well beyond the conventionally-designated Clackamas region. Missionaries from the competing denominations often visited his village, and sometimes set to the task of tearing down the flags, crosses, Catholic ‘ladders,’ and other instructional and ceremonial paraphernalia left by the other side; regrettably, the perspectives of Pohpoh and his people, for whom this must have been an odd spectacle, are poorly represented in the written record.

By the beginning of the 1840s, most of the non-resident congregation at the Fort’s Catholic mission was still reported to consist largely of Cascade and Klickitat origin, and the mission consistently reported strong ties to those populations. The Clackamas, too, were of growing importance as Pohpoh’s accounts suggest. Yet, a growing number of lower Columbia River region tribes were beginning to make regular visits to the Fort mission, both to participate in religious services and to coordinate the development of mission outposts in their own territories. Mission records show especially strong missionary ties with the Cowlitz:

“The Indians of Cowlitz love with reverence the missionaries who are established among them. They have a language of their own, different from that of the Chinook Indians. They also speak jargon. They are tolerably numerous but poor. They give us hopes of their conversion. After the visit of the Vicar General, they said to the settlers of Cowlitz: 'The priests are going to stay with us; we are poor, and have nothing to give them: Tlahowiam nesaika waik ekita nesaika: We want to do something for them, we will work, make fences, and whatever they wish us to do.' Several of them came to see the missionaries at Vancouver, and expressed the most ardent desire to have them come and remain with them” (in Blanchet 1878: 59).

Puget Sound tribes were also making frequent appearances at Fort Vancouver, apparently expressing interest in the development of missionary outposts in their homelands, providing the foundation for the extensive missionization efforts in western Washington in the years that followed. Simultaneously, such nearby groups as the Kalapuya seem to have avoided the priests initially, and were repelled even more by their efforts to convert them to Catholicism. Blanchet reported that “They wish to keep away from the missionaries as much as the Cowlitz Indians wish to be near them (in Blanchet 1878: 59). This may have been one of the many factors contributing to the comparatively small representation of Kalapuya among the Fort’s reported visitors and residents, generally.

Despite his sympathies for the Catholic missionaries, John McLoughlin was characteristically receptive to missionaries of all kinds, receiving and hosting them to a degree that often defied HBC policy. By the early 1840s, Fort Vancouver had become a staging ground place for missionaries of all kinds, with a strikingly nondenominational quality despite the established Catholic mission at the Fort and almost constant friction between some denominations. McLoughlin even allowed for the temporary designation of space within the Fort for ‘competing’ missionaries to perform their services while they stayed as his guests. In 1841, upon arriving at the Fort, Charles Wilkes noted a surfeit of missionaries enjoying McLoughlin’s hospitality:

“I was introduced to several of the missionaries: Mr. and Mrs. Smith, of the American Board of Missions; Mr. and Mrs. Griffith, and Mr. and Mrs. Clarke, of the Self-supporting Mission; Mr. Waller of the Methodist, and two others. They, for the most part, make Vancouver their home, where they are kindly received and well entertained at no expense to themselves. The liberality and freedom from sectarian principles of Dr. M’Laughlin may be estimated from his being thus hospitable to missionaries of so many Protestant denominations, although he is a professed Catholic, and has a priest of the same faith officiating daily at the chapel. Religious toleration is allowed in its fullest extent. The dining-hall is given up on Sunday to the use of the ritual of the Anglican Church, and Mr. Douglass or a missionary reads the service” (Wilkes 1845: 331).

Yet social divisions between the HBC leadership of the fort and the missionaries are apparent in various sources. Wilkes notes that the fort leaders and missionaries consistently sat at different tables when eating and McLoughlin maintained an aloof distance from any visiting missionaries in his official correspondence, despite his material aid to their efforts. No doubt, official HBC opposition to the aiding of American expansions within the region – an expansion for which many of these missionaries served as the vanguard contributed to McLoughlin’s attitude, his own personal views notwithstanding.

Conversion and Resistance

Despite varied responses to their mission, Demers, Blanchet, and their fellow missionaries were highly successful in developing a ministry that expanded throughout the region, aided by the material support and unique advantages of the HBC. Their official reports suggested that, by 1845, “six thousands pagans have been converted” (in Blanchet and Demers 1956: 232). Despite the apparent success of these missionary efforts, however, it is important to remember that indigenous ceremonial traditions remained strong in communities throughout the lower Columbia region during this time. In the journals of the missionaries, protestant missionaries especially, there can be found almost incessant complaints about the persistence of indigenous customs and beliefs among the native people of the lower Columbia (e.g., Bolduc 1979; Lee and Frost 1844). In many Indian communities, both Catholic and protestant rites were often adopted into a larger suite of preexisting ritual traditions, with “conversion” being seen by these communities as a way of enhancing their existing ritual capacities rather than – as missionaries often wrongly believed - as a means of replacing one set of religious beliefs and practices wholly with another. “Conversion” was also occurring very unevenly within these tribal communities. As Blanchet lamented in one of his reports, for example, “Keiinsno chief of the Indians below Vancouver, said to his people: “Follow the priest if you like, for myself, I am too bad, I am unable to change. I will die the same” (in Blanchet 1878: 121-22). There were strong incentives for missionaries to report to their superiors and supporters accounts of the successful and complete conversion of communities; so too, there were many reasons to question the veracity of their accounts.

Nonetheless, it is clear that the presence of the Catholic mission at Fort Vancouver, as well as the other missions that arose and diffused from this hub, contributed to the great cultural diversity of the Indian community regularly visiting the Fort, and arguably added to the diversity of the resident population as well. Through the 1840s, many missionary accounts mention the Fort as a stopover or as a base of operations, as these missionaries made inroads with Flatheads, Blackfeet, Clatsop, and many others. Under the direction of the Fort Vancouver mission, Catholic missions were developed in Puget Sound, with both missionaries and Sound tribes making frequent journeys between the two places. 232 Fort Vancouver served as the launching point for initial missionary efforts in British Columbia as well, resulting in similar interregional traffic. The reach of these missionary efforts was arguably as extensive as the reach of the Fort, itself, and served to reinforce Fort Vancouver’s role as a gathering place of indigenous peoples from throughout the northwestern portion of North America. While there were many other missionary efforts in the 19th century Northwest, the role of the Fort Vancouver mission was perhaps unique in its scale, scope, and its capacity to bring together peoples from the far corners of the Oregon Territory.

NPS Photo