Part of a series of articles titled National Fossil Day Logo and Artwork – Prehistoric Life Illustrated.

Article

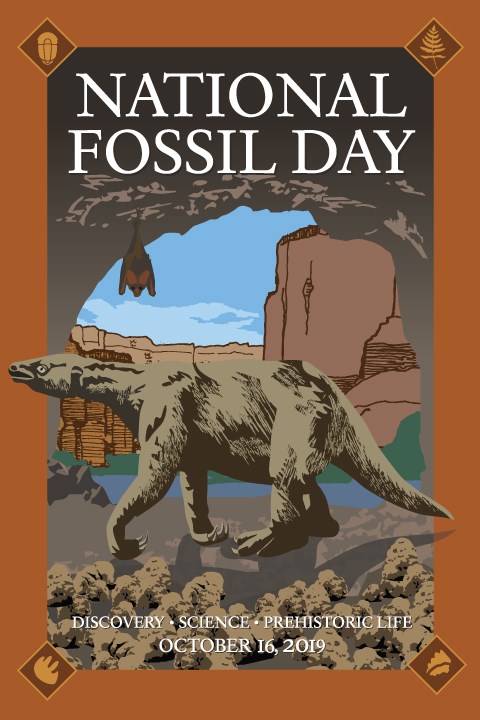

Fossils of the 2019 National Fossil Day Artwork

Grand Canyon National Park: 100 Years of Fossil Discovery

The majesty of the Grand Canyon has long inspired adventurers, artists, scientists, and other visitors. The 2019 logo artwork honors the 100th anniversary of the establishment of the Grand Canyon National Park, which occurred on February 26th, 1919 by President Woodrow Wilson. The Grand Canyon also inspired previous presidents such as Benjamin Harrison and Theodore Roosevelt, both of whom worked to preserve this land during their administrations.

Over millions of years, the Colorado River and its tributaries have carved the canyon, cutting through geologic layers revealing the pages of deep time. Many of these layers hold rich fossil records. The majority of the fossil-bearing rocks of the Grand Canyon represent the Paleozoic Era. The oldest of these fossils are approximately 540 million years in age (Cambrian Period). The youngest Paleozoic fossils are 260 million years in age (Permian Period). Paleozoic fossils from the Grand Canyon include some of the oldest evidence of invertebrate animals, ancient plants, early reptiles, and ancient fish. The border corners of the 2019 National Fossil Day artwork shows some notable Paleozoic fossils from Grand Canyon National Park: a trilobite from the Cambrian Bright Angel Shale; a fern from the Hermit Formation; a footprint of Chelichnus, a mammal-like reptile from the Coconino Sandstone; and the large tooth of Megactenopetalus, a shark from the Kaibab Limestone.

Though there is a rich fossil history from the Paleozoic Era at the Grand Canyon, some of the most well-studied fossils from this National Park come from the end of the Cenozoic Era (66 million years to today). These fossils are from the late Pleistocene Epoch (40 thousand to 10 thousand years ago) and show evidence of a different Grand Canyon than what we see today. Fossils of Pleistocene plants and animals have been found in caves and crevices sites along the full length of the Grand Canyon. One of the best Pleistocene cave sites in the Grand Canyon, Rampart Cave, is the focus of the 2019 National Fossil Day Artwork.

Rampart Cave: An Ice Age Tomb of the American Southwest

The 2019 National Fossil Day artwork depicts the entrance of Rampart Cave 11,000 years ago. A Shasta Ground Sloth, Nothrotheriops shastensis, is entering the cave and the ground is carpeted with its large droppings. A vampire bat, Desmodus stocki, roosts in the cave ceiling while it awaits for nighttime to forage for food.

Rampart Cave is a dry cave formed in the Redwall Limestone and was discovered in 1936. It is located at the far western end of Grand Canyon National Park, near its border with Lake Mead National Recreation Area. The first collection from 1936 included the skin, hair, and bones of the Shasta Ground Sloth, the extinct Harrington’s mountain goat (Oreamnos harringtoni), big horn sheep (Ovis canadensis), an extinct horse, and a large extinct cat. The continuous dry environment of the cave allowed for the preservation of hair and skin. In 1942, a field team from the Smithsonian Institution did a more extensive excavation of Rampart Cave which led to the discovery of the extinct vampire bat and many other fossils. At present, fossils of 37 species of reptiles, birds, and mammals have been found at Rampart Cave.

Fossil plant evidence from sloth dung and packrat middens from inside the cave showed a rich fossil flora occurred outside. Many of the fossil plants are still found alive in modern times but the fossils show that the distribution of these plant species differed to their modern counterparts. 11,000 years ago the area around Rampart Cave had a higher distribution of pinyon juniper woodlands and some desert adapted vegetation. Today, the pinyon juniper woodlands have retreated to higher elevations and the area around the cave is dominated by desert plants. The number of plant and animal species found at Rampart Cave make it one of the richest Late Pleistocene fossil sites in North America.

Shasta Ground Sloth: Mega Pooper

The extinct ground sloths are related to the smaller living tree sloths found in Central and South America. There are currently six species of sloths living today. Fossils of ground sloths are only known from the Americas, including some islands in the Caribbean, and they went extinct near the end of the Pleistocene. During the late Pleistocene at least four species of ground sloths species occurred in North America with the largest ground sloths reaching 20 feet in length and estimated to have weighed more than 3 tons. The Shasta Ground Sloth was a smaller species of sloth, reaching 9 feet in length and weighing approximately 550 lbs. The Shasta Ground Sloth lived primarily in the American Southwest, but fossils of this species have also been found in Florida.

By studying the fossil poop (coprolites) of Shasta Ground Sloths, we know that these sloths ate various kinds of plants, including cacti, yucca, and desert globemallow. This sloth may have also played an important role in the distribution of such plants such as the Joshua tree (Yucca brevifolia), as seeds of this plant is commonly found in their coprolites. Rampart Cave is particularly famous for the large number of Shasta Ground Sloth coprolites found inside. At least two dense layers of sloth dung are recognized at Rampart Cave, with the depth in some sections of the cave reaching 20 feet deep. The oldest sloth dung layer was dated between 40,000 to 24, 000 years ago and the youngest layer between 13,000 and 11,000 years ago. This suggests that there were at least two separate periods of sloths using the cave. Unfortunately, the Rampart Cave sloth dung was almost completely destroyed in 1976 by a fire that burned for many months. A large gate now covers the cave to keep vandals out and prevent further damage.

The Canyon Vampire

Vampire bats are a unique sub-family (Desmodontinae) of bat that feeds exclusively on blood, and are considered micropredators that parasitize (an organism that feeds in part off of living organism) other warm-blooded vertebrates. Vampire bats are thought to have diverged from other New World leaf nosed bats (Family Phyllostomidae) around 26 million years ago, and there are at least 3 species of living vampire bats. These bats feed by using enlarged blade-like incisors and canines to make small wounds on larger mammals and birds and lapping blood. The saliva of vampire bats contains anticoagulants which suppresses blood clotting to allow them to feed longer.

Desmodus stocki is an extinct vampire bat that lived in North America from 120,000 years ago to around 5,000 years ago. Living vampire bats are only found in South America, Central America, and southern Mexico. Desmodus stocki was approximately 20% larger with larger and more robust teeth than the living Common Vampire Bat (Desmodus rotundus) from Central and South America. Fossils of Desmodus stocki have been found in northern Mexico, California, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Florida, and Virginia. Desmodus stocki fossils are also commonly associated with the fossils of ground sloths, suggesting this extinct vampire bat may have fed on ground sloths. Rampart Cave has produced a skull and a couple of fragmentary skeletons of Desmodus stocki and was probably a roosting site for these bats.

The Survivors

Many of the fossil plant and animal species found at Rampart Cave are still alive today, though some are no longer found in the Grand Canyon. The survivors include the bighorn sheep which is known from Pleistocene fossils throughout the Grand Canyon and still resides there today. Other living mammals found as fossils at Rampart Cave and still living in the canyon include ringtails, spotted skunks, bobcats, American porcupines, ground squirrels, jackrabbits, cottontails, and packrats. Only the yellow-Bellied marmot (Marmota flaviventris) no longer occurs in the Grand Canyon and today lives farther north.

Fossils of birds from Rampart Cave include remains of the endangered California condor, turkey vultures, barn owls, red-tailed hawks, and golden eagles, all of which still reside in the Grand Canyon today. The California condor (Gymnogyps californianus) was once widespread in the American Southwest but went extinct in the wild by the late 1980s. However, successful captive breeding programs allowed for the reintroduction of this large magnificent bird in the Grand Canyon.

References

Carpenter, Mary C. (2003) Late Pleistocene Aves, Chiroptera, Perissodactyla, and Artiodactyla from Rampart Cave, Grand Canyon, Arizona. Master’s Thesis, University of Northern Arizona, Flagstaff.

Kenworthy, J., V. L. Santucci, and K. L. Cole (2004) An Inventory of Paleontological Resources Associated with Caves in Grand Canyon National Park. In The Colorado Plateau, Cultural, Biological, and Physical Research, edited by C.V. Riper III and K.L. Cole, pp. 211-228. University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

Mead, J. I., N. J. Czaplewski, and L. D. Agenbroad (2005) Rancholabrean (Late Pleistocene) Mammals and Localities of Arizona. In Vertebrate Paleontology of Arizona, edited by R.D. McCord, pp. 139-180. Mesa Southwest Museum Bulletin No. 11.

Miller, L. (1960) Condor Remains from Rampart Cave, Arizona. Condor 62:70.

Phillips, Arthur M., III (1984) Shasta Ground Sloth Extinction: Fossil Packrat Midden Evidence from the Western Grand Canyon. In Quaternary Extinctions: A Prehistoric Revolution, edited by P.S. Martin and R.G. Klein, pp. 148-158. University of Arizona Press.

Santucci, V.L., J.P. Kenworthy, and R. Kerbo, 2001. An inventory of paleontological resources associated with National Park Service caves. National Park Service Geologic Resources Division Technical Report NPS/NRGRD/GRDTR-01/02, 50 pp.

Van Devender, T. R., A. M. Phillips, and J. I. Mead (1977) Late Pleistocene Reptiles and Small Mammals from the Lower Grand Canyon of Arizona. Southwestern Naturalist 22:49-66.

Wilson, R. W. (1942) Preliminary Study of the Fauna of Rampart Cave, Arizona. Contributions to Paleontology 6. Carnegie Institute of Washington Publication 530:169-185.

Related Links

-

University of Texas at El Paso—Quaternary Vertebrate Sites—Rampart Cave

-

Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida—Desmodus stocki

Learn more about National Fossil Day and the NFD Logos and Artwork on the official National Fossil Day website.

Last updated: July 8, 2024