Last updated: October 24, 2018

Article

Coastal Defense: Fort Hancock during World War I

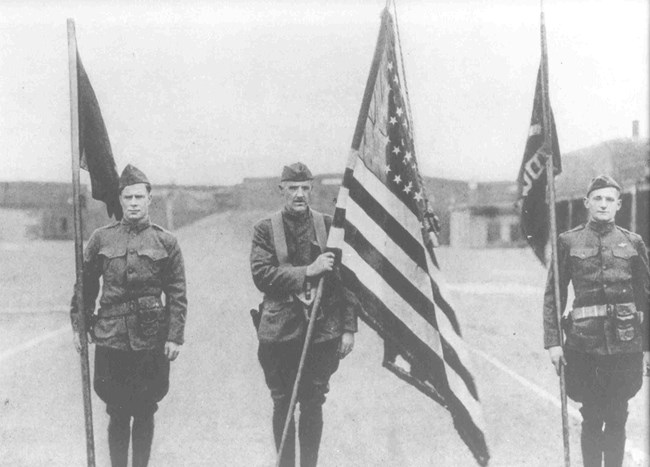

NPS Photo

As long as there has been a United States, there has been an acknowledgement of the need to protect it through the creation, maintenance, and operation of a series of coastal fortifications. At Sandy Hook, the entrance of Lower New York Harbor, Fort Hancock has been part of an older system of fortifications protecting one of the nation's largest and most important cities since 1859.

In 1917, Fort Hancock’s peacetime garrison consisted of about 600 regular army soldiers, performing routine but essential garrison and artillery duties. These included maintaining and practicing with the fort’s rapid fire guns, heavy caliber guns, mortars, searchlights, and range finding system, as well laying and retrieving underwater mines. Other branches of the Army jokingly referred to the soldiers of the Coast Artillery Corps as “Cosmoliners” or “Cosmoline Soldiers”, referring to the thick oil used to preserve the bores and metal parts of guns and mortars from salt air, implying that the guns were never fired.

Yet, when the US declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917, the fort’s defensive apparatus quickly clicked into place. A combination of new enlistees and draftees swelled the Army’s ranks in the summer of 1917. In addition to maintaining the fort’s defenses, a “Camp of Instruction” provided training for new army units who would be sent overseas to see action on the Western Front in France, armed with the latest technology in artillery which had been tested at Fort Hancock.

One such soldier, Sergeant Max Duze, a Russian immigrant who joined the Army in 1912, served in France on the Western Front. His artillery unit came under a German artillery barrage by surprise one night, as soldiers had already readied themselves for sleep. Max, in stocking feet, ran out to help a wounded soldier yelling for help after the attack came, and in doing so was later awarded the Silver Star, the Army’s third highest award for valor. As Max’s son Bernie Duze explained “After the war, a lot of the young soldiers serving at Fort Hancock during the 1920’s to when he retired from the army in 1941 thought my father never saw any action. They just didn’t know that my father served in France and got the Silver Star because my father never talked about it.”

In the summer of 1917, the garrison at Fort Hancock grew as new Army units were organized. Initially housing soldiers in tent cities, post commander Lieutenant Colonel Delamere Skerrett ordered the construction of 27 66-person wooden barracks, 11 wooden mess halls, 11 wooden latrines, 14 wooden officer’s quarters, and a storehouse and guardhouse that would be more suitable for the approaching New Jersey winter. Facilities for a growing Army would continue to expand under the leadership of subsequent post commander Colonel Henry L. Harris.

By mid-April, 1918, the Fort Hancock garrison contained 4,043 officers and soldiers, continuing to train and maintain the coastal fortifications anti-aircraft defenses. After the end of the war November 11, 1918 and the subsequent rapid demobilization of American military forces that followed, by February 28, 1919, there were only 30 officers and 656 enlisted soldiers on duty at the post.

With the end of the war, Fort Hancock soon settled back into the routine of a peacetime garrison. The influx of soldiers serving and training at the post was over, leaving behind many empty wooden barracks, mess halls, and other support structures. Believing the “war to end all wars” really marked the last armed conflict in American history, the structures were all demolished by the mid-1930s. After all, what was the need for this infrastructure, in a future of perpetual peace?