Last updated: August 22, 2019

Article

Bat Population Monitoring at Fire Island National Seashore

NPS photo

Why is the National Park Service interested in bats?

Bats are an important part of ecosystems and food webs. Though some species of bats feed on fruit, seeds, or pollen, the species that live in New York are insectivores. They consume huge numbers of insects every night, filling a unique ecosystem role as nocturnal insect predators. Unfortunately, a new disease called white-nose syndrome is affecting bats across the United States. To better protect bats, biologists are studying how local bat populations are changing.

Research Highlights

- Seven species of bats have been documented at the seashore, including a federally and state threatened species—the northern-long eared bat.

- Excitingly, northern long-eared bats are now known to be reproducing near the William Floyd Estate.

- It is possible that Long Island is serving as a refuge for this rare species.

Bat species found at Fire Island National Seashore

Hibernating bats

- Big brown bat (Eptesicus fuscus)*

- Eastern small-footed (Myotis leibii)*

- Northern long-eared bat (Myotis septentrionalis)*

- Tri-colored bat (Perimyotis subflavus)*

Migratory bats

- Eastern red bat (Lasiurus borealis)

- Hoary bat (Lasiurus cinereus)

- Silver-haired bat (Lasionycteris noctivagans)

*bat species susceptible to white-nose syndrome

How do biologists study bats? What have they learned about bats at the seashore?

Biologists use a variety of techniques to study bats. Bats use echolocation to navigate and catch insect prey during the night. People can’t hear these bat calls, but biologists can use special microphones, called acoustic detectors, to record the sounds. By analyzing the bat calls, biologists can identify which bat species are present in an area.

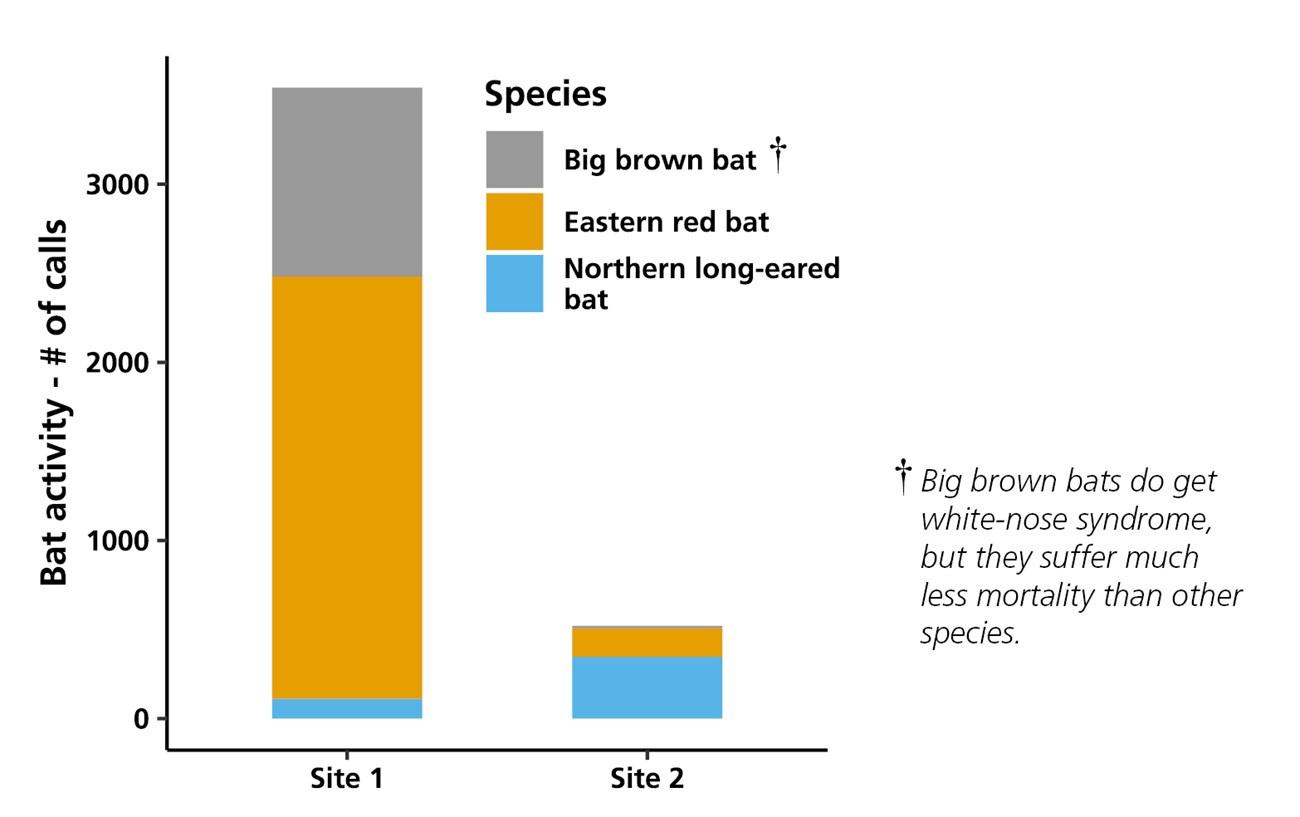

To date, seven species of bats have been documented across Fire Island and at the William Floyd Estate, a separate unit of the seashore located on Long Island. In 2017, two acoustic detectors were deployed at the William Floyd Estate. At one site, eastern red bats (Lasiurus borealis) were the most commonly detected species. Eastern red bats migrate south for the winter and are not susceptible to white-nose syndrome. At the second site, the most frequently detected bat was the federally threatened and state endangered northern long-eared bat (Myotis septentrionalis).

Across the Northeast, northern long-eared bat populations have been decimated by white-nose syndrome. Excitingly, in 2018, researchers determined that northern long-eared bats were reproducing at the William Floyd Estate. Over the next few years, biologists plan to study this local northern long-eared bat population. Female northern long-eared bats can be captured and outfitted with tiny radio tracking devices. Biologists can then track the females to the “maternity roost” where the bats are raising their young. Once the location of the maternity roost is identified, the roost site (e.g. hollow tree, building, etc.) can be better protected by seashore managers.

Additional data indicates that northern long-eared bats remain relatively common on Long Island, and it’s possible that Long Island is serving as a refuge for these rare bats. Why is this the case? Scientists aren’t sure, but ongoing research will hopefully help answer this important question.

NPS photo / Morgan Ingalls

What is the seashore doing to protect bats?

The data being collected on bats is helping seashore managers conserve bats and their habitat. Protecting maternity roosts where bats raise their young will help local populations while scientists study how to better manage the disease. There is still much to learn and research efforts will continue. White-nose syndrome is an extraordinarily dangerous threat to bats—sadly, some species may ultimately disappear from the region.

Want to learn more?

For more information:

Contact National Park Service Biologist Lindsay Ries.

Download a printable pdf of this article.