Last updated: April 7, 2022

Article

These Great Present & Future Problems: Erica Thorp and WWI French War Orphans

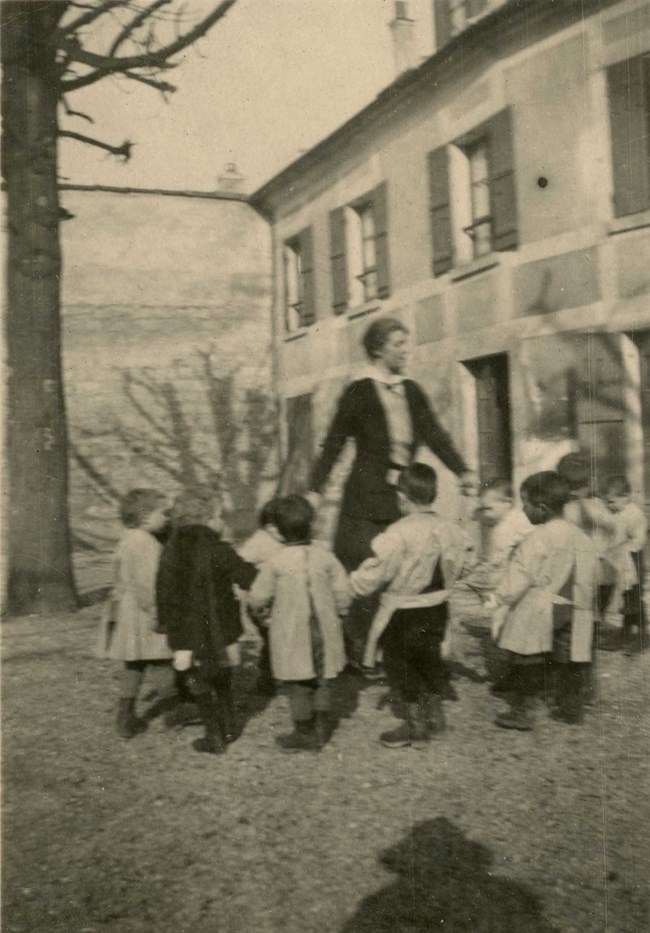

Longfellow Family Photograph Collection, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters NHS (3007-2-2-3-52)

When Franz Ferdinand was assassinated on June 28, 1914, and the world responded with the outbreak of World War I, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s granddaughter Erica “Bunny” Thorp was on an extended tour in Europe with her aunt Alice Longfellow. Initially, they did not realize the full severity of the war that was to come and simply continued their travels; however, they knew they must return home when it became apparent that this would be warfare on a massive scale. It took several weeks for them to find a way to reach the United States, and Erica was swept up in emotions and enthralled by the idea of war. Before safely returning home in September 1914, she wrote the following in a letter to her father:

It is all so incredible that at times it seems all a dream. Yet to live in the midst of it & feel the pulsations of all the varying emotions—heroism, grief, stoical calmness, and the united unfaltering wish to lay down lives for France is beyond any thing I have ever imagined. It makes one’s whole past experience seem so perfectly insignificant beside the tremendous realities—the incalculable horror of this world-war! (3 August 1914)

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Family Papers, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters NHS (1006-15-39)

Erica was fascinated by the stimulation of war and the way in which it made people feel a profound sense of purpose in their lives. Thus, it is no surprise that soon after the United States entered the war in 1917, she put her life in America on hold to travel to France to work at a colony for orphaned boys, which also welcomed those whose parents were away fighting for the war effort. The colony was originally situated in the Parisian suburb of Presles, but the school was relocated to Lacaune-les-Baines in southern France in late March 1918 because bombings in Paris were becoming more and more frequent and dangerous. Erica continued her work at the colony through the end of the war and into 1919 as well. She found immense pleasure in nurturing these boys and providing for them when no one else was able.

Teaching came naturally to Erica, who had trained in educational work with Maria Montessori in Italy, and she came to France prepared to implement all she had learned. She reflected in letters home to her family on the enormity of the task in front of her:

It’s all so extraordinary, so incredible – the circumstances that one finds oneself suddenly in thro’ some strange trick of fate. I grow dumb with amazement each day at the thought that I’m really here – a part of this great constructive process with the opportunities of several lifetimes before us. By the pure good fortune of once being able to get over, here I am I with such comparatively small experience behind me, thrown into the midst of these great present & future problems, in touch with some of the keenest American minds – and perhaps later, French ones also – all because I’m on the spot – and the need of workers is so great. It leaves you gasping, but “yours not to reason why” – you just plunge into it, and wonder if it can be you. (10 December 1917)

She scoured Paris for any school supplies that were available in wartime France and tried to provide the children with the most normal school experience possible. The colony in which she worked was run by nuns and involved a religious education, but Erica was also able to implement some of the practices from the Montessori Method, which emphasizes a holistic and experiential learning environment. Once they settled in, the countryside proved to be a peaceful retreat for the boys. In addition to their academic studies, they would often go on walks and enjoy the outdoors. Erica said that “a more perfect paradise for children never existed” (3 April 1918). Over time, Erica transitioned into more of an administrative role where she was responsible for acquiring supplies, housekeeping, and discipline. She wrote, “I thought I was pretty close to them before, but it was nothing to the present ‘mere de famille’ feeling, beginning with ringing the 6.30 rising bell and ending with tucking them all in and giving medicines and putting on vaseline to chapped hands” (15 October 1918). Her adoration for children is obvious here, and she expresses her love for the boys over and over again in her letters.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Family Papers, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters NHS

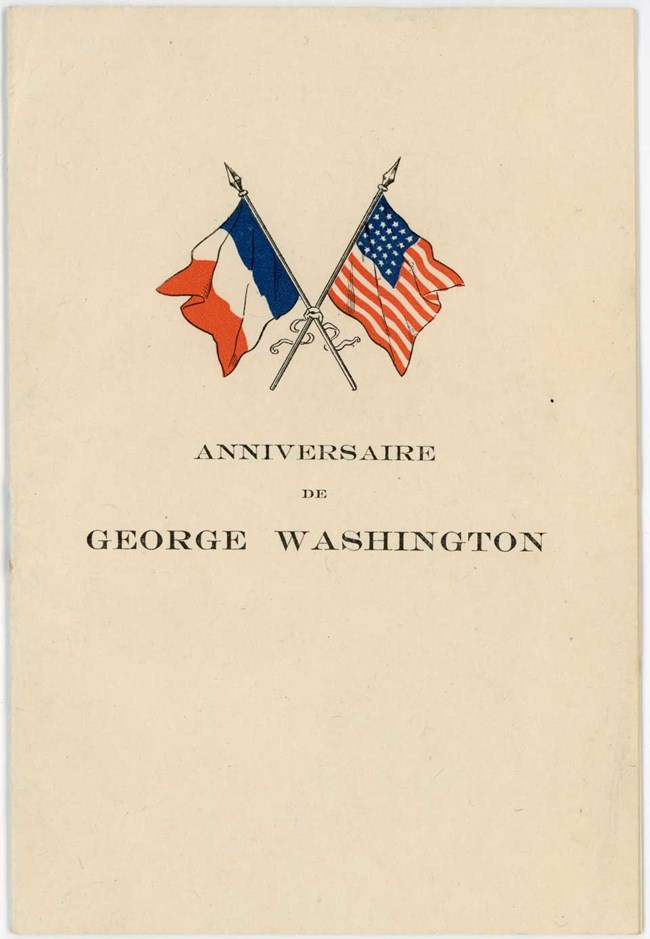

Erica had a passion for France and its culture, but she was also very proud of her nation’s history and all the work American servicemen and women were doing for the war effort. Having grown up down the street from her grandfather’s home, which had served as Washington’s first headquarters in the American Revolution, Erica was steeped in the family’s respect and admiration for the president. Erica sought to convey this heritage to her students and consulted with the Committee Franco-American to provide pamphlets commemorating the occasion of Washington’s birthday for the boys at the colony in 1919. To celebrate, “various Revolutionary-Washingtonian views” were shown, including Washington’s Cambridge headquarters, on which Erica remarked, “always la maison du grandpere de Melle Erica causes great excitement, especially this time when it appeared as W’s headquarters” (3 February 1919).

Erica remained amazed by the spectacle of war throughout her time in France, but over time she became more mature in her understanding of the harsh realities of war. Upon her arrival in Paris, Erica described mid-war Paris as “a marvelous medley of color” with all the commotion of busy streets made even more crowded by soldiers in uniform (12 September 1917). However, about a month later when she visited a military hospital at Le Val de Grace for what she called her “baptism of fire,” Erica wrote, “previous imaginings of the horror of war vanish into nothingness before the reality of seeing what this thing can do, and one awakes to the full realization of the folly and madness of settling ideals by hacking men to pieces bit by bit” (14 October 1917). Nearly 6 months later, she wrote, “Don’t think that I see only the light side of it. On the contrary the oftener it occurs the less one feels the excitement and spectacular side, and the more brutal destruction, and ghastly cruelty” in a letter to her Aunt Alice (24 March 1918). Bombings had become a regular part of life, and Erica learned to trade her feelings of intrigue and excitement for those of sympathy and compassion.

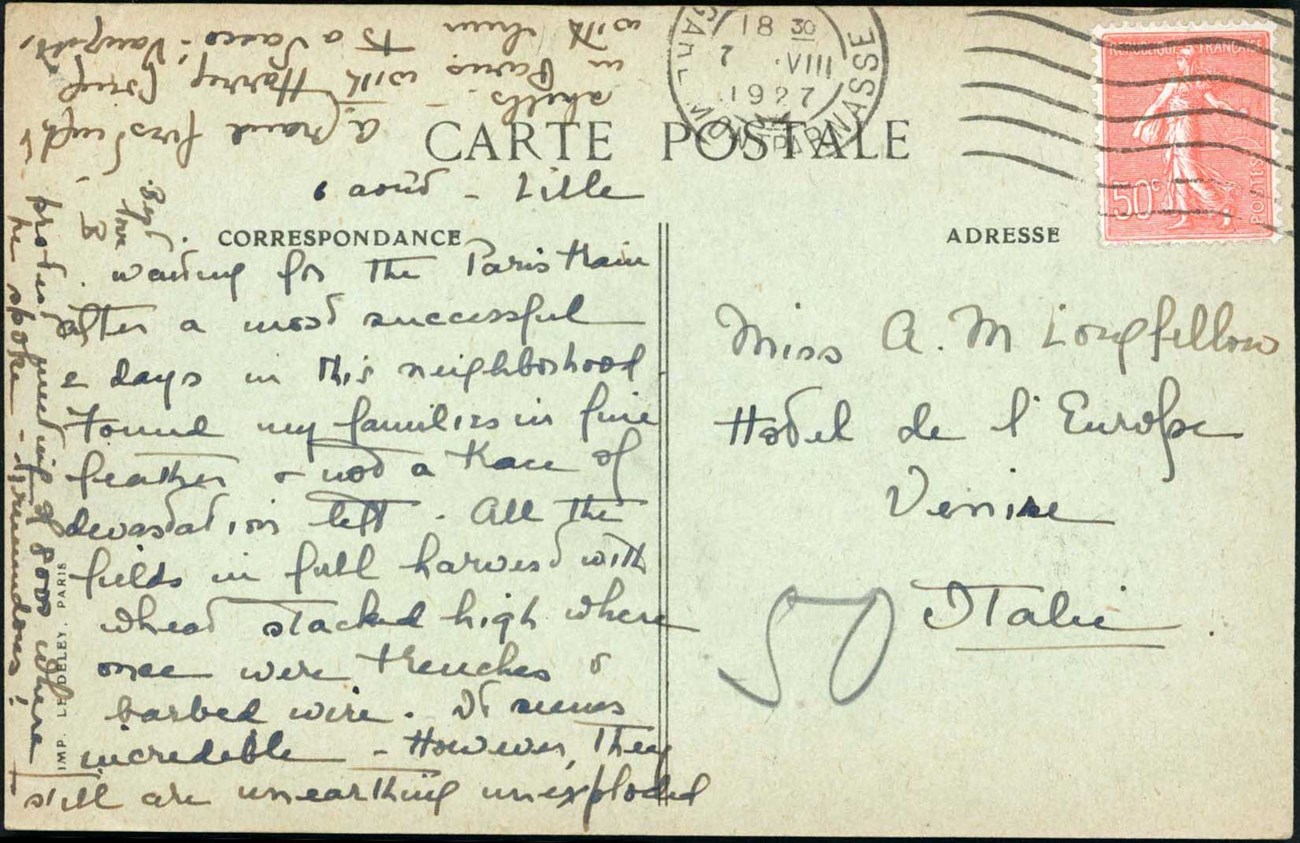

Alice M. Longfellow Papers, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters NHS

Despite the destruction that resulted from the Great War, Erica maintained her love affair with Europe and returned to France in 1927. She sent her Aunt Alice, who was also abroad in Venice at the time, a postcard that reads, “Found my families in fine feather & not a trace of devastation left. All the fields in full harvest with wheat stacked high where once were trenches and barbed wire. It seems incredible.” (6 August 1927). Life had come full circle when they both returned to see Europe in a state of peace. There was no way for them to predict that in 12 short years the world would once more be at war.

Sources

Series IV-F. Erica Thorp de Berry (1890-1943), Section 2. Correspondence, Outgoing, in the Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882) Family Papers (LONG 27930), Longfellow House-Washington’s Headquarters National Historic Site.

National Parks and the Great War

World War ITags

- longfellow house washington's headquarters national historic site

- wwi

- women

- history

- education history

- france

- humanitarian relief

- society

- women at war

- women in history

- women's history

- women in the world community

- us in the world community

- women and education

- world war i

- women in wartime

- european american heritage

- education