Part of a series of articles titled Democracy Limited: The Suffrage "Prison Special" Tour of 1919.

Previous: Democracy Limited: Introduction

Article

“The militancy of men, through all the centuries, has drenched the world with blood. The militancy of women has harmed no human life save the lives of those who fought the battle of righteousness.” —Emmeline Pankhurst

In January 1917, the National Woman’s Party began an unprecedented campaign of picketing outside the White House. Led by Alice Paul and Lucy Burns, the NWP had split from the larger and older National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Paul and the NWP believed that NAWSA was moving too slowly in the fight for suffrage. They aimed to get faster results by pressuring the president, Woodrow Wilson, directly. They borrowed aggressive strategies from British suffragettes. British leaders like Emmeline Pankhurst engaged in direct action protests. Despite public criticism that pickets were “unladylike,” the NWP forged ahead with them.

From the collections of the Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/item/mnwp000293).

In January of 1917, groups of suffragists began protesting six days a week outside of the White House. These "Silent Sentinels" called on President Wilson to support the suffrage amendment. At first, reactions were positive. But after the United States entered World War I in April 1917, public opinion began to turn against the picketers. Many Americans felt that criticism of the government during wartime was unpatriotic and even treasonous. But the NWP refused to stop picketing.

From the collections of the Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/static/exhibitions/women-fight-for-the-vote/images/objects/ws0097_standard.jpg).

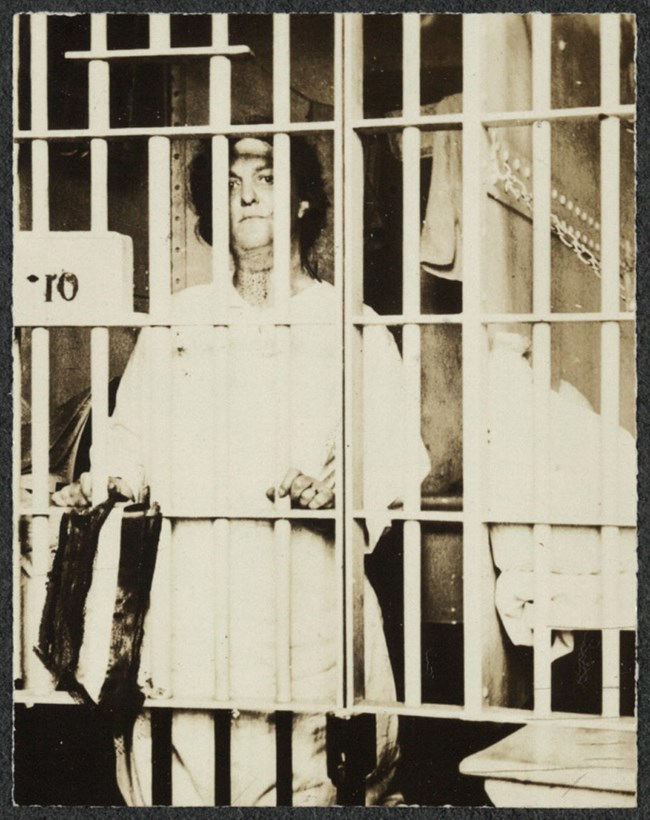

The protests infuriated Wilson and much of the public. Police began to arrest Sentinels on charges of “obstructing traffic.” In November 1917, 41 women including Lucy Burns, Dorothy Day, Dora Lewis, and Mary Nolan, were arrested for their protests. They were sentenced to jail for periods ranging from six days to six months at the Occoquan Workhouse in Lorton, Virginia. The workhouse was a minimum-security prison, but that did not mean that the mostly poor and working-class women there were well treated. They experienced brutality from the guards, poor food, and dirty conditions. The middle-class white suffragists who arrived at Occoquan quickly got a window into this world.

The suffragists’ second night in Occoquan became known as the Night of Terror. Guards attacked the women once at the workhouse, throwing them around, hanging them by their arms, and denying them food and medical care.

From the collections of the Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/resource/mnwp.160039).

In both Occoquan and the District of Columbia prisons in which they were held, the women were denied contact with the outside world. They were rarely allowed visitors and not allowed to write letters. Protesting their treatment in jail, several suffragists, including Alice Paul and Lucy Burns, began hunger strikes. In response, prison guards restrained and force fed them.

Those on the outside learned of this treatment through notes smuggled out of prison. Once the public heard about the treatment of the suffragists, many Americans who were not sympathetic to the cause of women’s suffrage were horrified at how these women were being treated. It wasn’t long before action was taken. Public outrage and the efforts of several well-connected women forced the government act. Alice Paul’s seven-month sentence was commuted and she was freed after 5 weeks. The women of the National Woman’s Party decided to use the public outrage about their treatment in prison to further their mission. They created the Prison Special to spread their first-hand accounts of what they had suffered in prison. By sharing their stories with the public, they gained a new platform for arguing for women’s full voting rights.

"Detailed Chronology - National Woman's Party History." Women of Protest: Photographs from the Records of the National Woman's Party. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/static/collections/women-of-protest/images/detchron.pdf.

"Emmeline Pankhurst." BBC.com. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/pankhurst_emmeline.shtml.

Paul, Alice. "Conversations with Alice Paul: Woman Suffrage and the Equal Rights Amendment. Interview by Amelia R. Fry. University of California, 1976. http://content.cdlib.org/view?docId=kt6f59n89c&query=&brand=calisphere.

Stevens, Doris. Jailed For Freedom. New York: Boni & Liveright, 1920.

by Brianna Nuñez-Franklin

Part of a series of articles titled Democracy Limited: The Suffrage "Prison Special" Tour of 1919.

Previous: Democracy Limited: Introduction

Last updated: May 21, 2020