Article

Cuyahoga Valley Railway Cultural Landscape

NPS

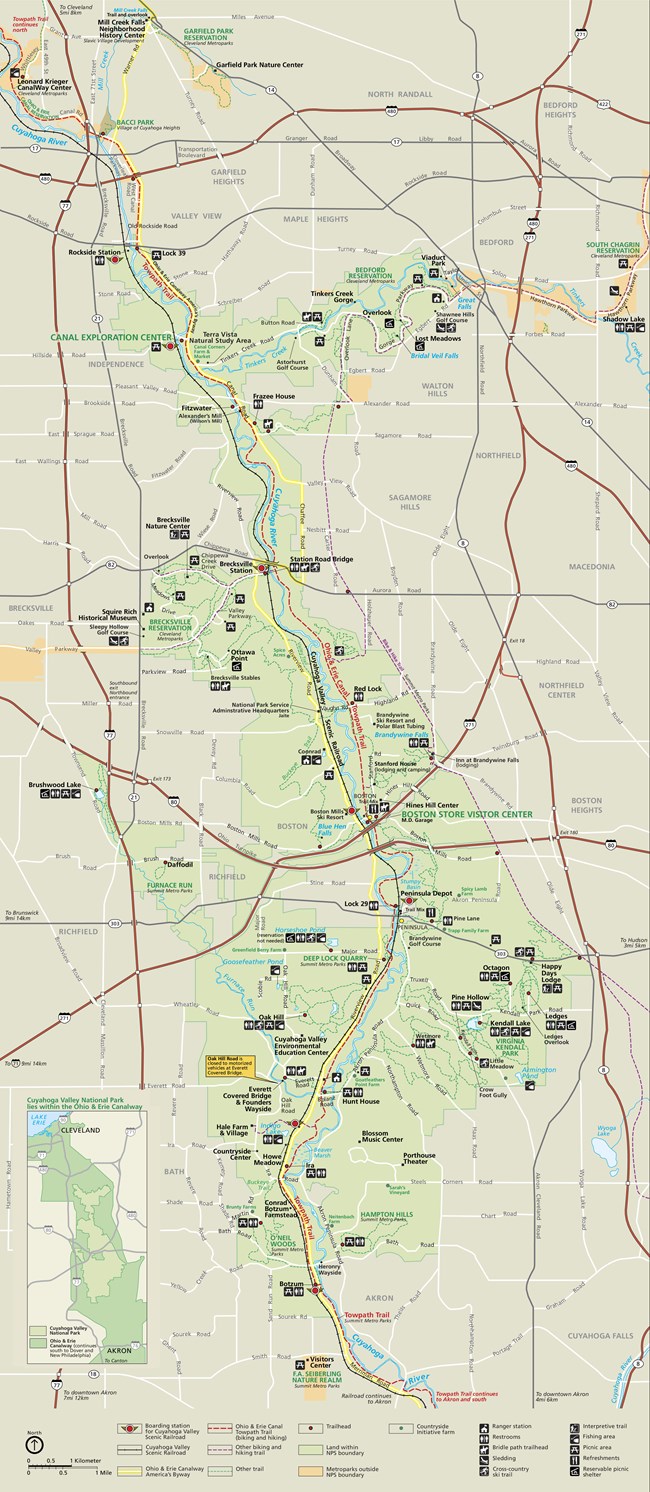

Located at the northern terminus of the Cuyahoga Valley of north-central Ohio, Cleveland-based industrialists believed they could simultaneously become wealthier while also establishing Cleveland as a nationally recognized port on Lake Erie. The key element in establishing the Valley into a commercial rail center, the industrialists believed, was to create some manner of delivering heavy ores, freight, and passengers from Lake Erie to Akron. As the railway evolved into an everyday part of life for Valley residents, small hamlets such at Boston, Peninsula, Independence, Brecksville, and Botzum were quickly transformed into important depots which represented a local connection to the nation’s growing dependence to ship goods and passengers from coast to coast by rail.

The Ohio & Erie Canal System

To gain a true understanding of the Valley Railway’s significance, it is important to place the line’s existence into historical perspective. By 1827, many of the nation’s materials producers relied on a federally supported system of canals to transport goods and passengers while also connecting the Great Lakes with the Mississippi River. Flat-bottomed boats, usually pulled by horses and mules, traversed the shallow waterways in journeys requiring one to three days. As the population of the nation increased and moved in a continual, westward-oriented direction, canals and rivers became the prime method of hauling goods cheaply from one market to another.

In 1827, residents of the Cuyahoga Valley depended on the Ohio & Erie Canal system to transport goods and passengers from its southern terminus at Akron to the wharfs and rail depots located at Cleveland. Running parallel to the Cuyahoga River, the Ohio & Erie Canal provided a dependable method of transportation which subsequently transformed the Valley landscape from a region which had previously based its economy on subsistence agriculture to one that was more market-focused. Now that a method of hauling the available resources was available to everyone, the economy of the Valley flourished and evolved with locally grown agricultural products being sent to more distant markets. Large warehouses to store the goods became more prevalent across the landscape, and canal construction crews and flatboat passengers discovered an increased number of housing opportunities.

The Rise of the Railroad

By the 1850s, however, railroads began to replace canals and riverboats as the primary method of heavyweight transportation. The state of Ohio entered the railroad age by laying tracks on an east-west axis as well as a southeast-southwest, diagonally-oriented line stretching across the state. These early rail lines provided factories located near or along the lines with a more efficient method of hauling their finished goods and sending them to consumers. This was especially true in the coalfields located at Mahoning Valley and the Tuscarawas Valley. During the 1860s, when Civil War-era military commanders discovered they could use the railroads to deliver large numbers of men and tons of material to depots located at or near the battlefields, America’s dependence on canal- and river based transportation methods gave way to a more technologically based delivery system that was faster and cheaper.

The nation’s technological landscape changed as a result of the Civil War and methods of transporting goods and people continued to improve in the coming decades. In 1869, when the Union & Pacific Railroad met at Promontory Point in Utah Territory, the driving of the golden spike linked the nation’s first transcontinental railroad. By 1870, the national population exceeded 38 million citizens, a 23% increase from the 1860 census. In 1871, the Great Fire swept through Chicago, taking the lives of more than 300 citizens as the flames covered much of the city over the course of two days. By 1880, the United States rail industry included more than 17,000 locomotives capable of carrying in excess of 236,000 tons of freight and 220,000 passengers per day. Clearly, America was on the move, and its citizens demanded that its railways continue to improve to meet the nation’s growing dependence on a rail system that met the demands of transporting goods and passengers nationwide.

Railroad Comes to the Cuyahoga Valley

But even as late as 1869, the Cuyahoga Valley remained without a rail system. In that year, Cleveland industrialist David L. King and other wealthy businessmen realized the longer the Valley endured the absence of a rail line, local merchants and consumers living in the region would remain dependent upon outdated transportation methods that were based on flat-bottomed canal boats, propelled by slow-moving horses and mules and moving at speeds well below those of the coal-powered locomotives. Unless a regional railroad was established, the Cuyahoga Valley would remain behind the times in a growing nation that waited for no one.

King and his associates understood that to ignore the technological needs of the Cuyahoga Valley was also to ignore progress. And for businessmen, there was no worse sin than to allow financial growth and profits to slip from their hands. Just before the end of the decade, King secured a charter for the Akron & Canton Railway which, in 1871, he renamed the Valley Railway. It became clear to Mr. King and his associates that linking the coalfields of Stark County and Tuscarawas County with Cleveland would create a domino effect of supplying other, eastern-based and coal-fueled factories with the valuable natural resources upon which the nation was becoming increasingly dependent. And, of course, as David King was certainly well-aware, the presence of a railroad running the length of the Valley presented generating considerable profits for himself and his fellow investors.

The Stark County Democrat. (Canton, Ohio), 29 April 1880. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Library of Congress.

By 1880, the Valley Railway extended southward from Cleveland to its southern terminus at New Philadelphia, Ohio. The most preferred route followed the Cuyahoga River and the old Ohio & Erie Canal primarily to utilize the naturally occurring landscape topography which included easily climbed grades and the wide curves of the river. David King’s vision was to transport rail passengers south from Cleveland to Akron and Canton then have the locomotives return with loads of coal from the Massilon fields was becoming a quick reality.

The initial segment of track laid by Valley Railway construction crews stretched fifty-seven miles from Cleveland to Canton. By 1884, an additional twenty-six miles of track had been laid, linking Canton with Valley Junction in Tuscarawas County. For the first time, the Cuyahoga Valley enjoyed a direct connection between the Wheeling & Lake Erie Railroad and the Cleveland & Marietta Railroad, two lines which transported goods to the east and the west. Sixteen depots lay along the length of the line as additional spur lines were laid to reach the valuable stone quarries at Peninsula, Boston Mills, and the Jaite Paper Mill. By 1891, the Valley Railway “contained seventy-five miles of mainline track, nineteen miles of branch track, and thirty-five miles of side track."[1] By 1888, hauling freight accounted for 75% of the line’s income with coal representing 44% of the tonnage transported to Cleveland and other cities. A robust passenger service also existed.

The Valley Railway crossed a wide variety of geographic landscape features. At Alexander’s Mill, tracks extended over bottom lands to Snake Flats Station Number One. It was here the valley’s natural landscape closed in on the track bed and forced work crews to reroute the direction of the rail line toward the west. After traveling alongside the old Ohio & Erie Canal route, the intermittently hilly terrain separated as the locomotive entered Snake Flat Station Number Two.

NPS

It was at this location that conductors steering the train encountered the most significant change in landscape: Still curving to the west, the tracks entered the Brecksville Rock cut, a fifty-foot shale cliff leading into the Brecksville depot. Travelling south from the Brecksville Depot, rail cars and locomotives crossed Chippewa Creek before passing through ‘Great Hog Back,’ an eighty-three foot cut given its name because of the presence of clay with a particular quality that seemed greasy to the touch. One mile south of the Peninsula depot, a spur line connected the quarries of the Cleveland Stone Company with the Amherst Quarries Company.

Change in Motion

Along the Valley Railway there were new structures built to accommodate the goods and people moving along the route. Bridges allowed the railroad to cross the ever changing topography. Mills which soon grew into company towns were constructed along the expanding route as farmers with large-sized barns embraced the railroad to ship their goods to markets in Cleveland or Akron. The railway improved economic conditions in the Valley by enabling farmers and merchants to ship their crops and specialty items such as cheese to distant markets and consumers where they’d not sold their goods before. Passenger depots were constructed at each of the growing number of stations and, in the same vein as where a mill had been established, quickly became established stopping points along the line. Depots began to offer a dependable telegraph service, while the number of customers requesting travel by rail increased.

Because of the Valley Railway’s limited ability to meet Cleveland’s growing need for fuel, factories in and around the city were forced to seek another rail company that was capable of delivering massive quantities of coal. Facing this shortage of resources, the board of the B&O declared the Valley Railway bankrupt and renamed the company the Cleveland, Terminal and Valley Railroad (CTVR).

The ultimate end of the formerly-named Valley Railway’s existence came in 1915 when the B&O assumed complete ownership of the CTVR. Five years later, in 1920, rail companies nationwide were forced to examine their role with the realization that there were cheaper and more efficient modes of transportation capable of carrying loads of coal, heavy ores, passengers and a wide variety of materials via the use of semi-trucks and more powerful locomotives. Because the region – and the nation – was now experiencing the positive commercial effects of alternative shipping methods, heavy reliance on rail service in the Cuyahoga Valley declined.

Additionally, privately-owned vehicles capable of traveling extended distances brought about a decrease in the railroad’s passenger service. By 1963, passenger rail service ceased entirely. By 1985, as a result of the line’s failure to employ a double-track system coupled with the loss of business, all commercial rail service in the Cuyahoga Valley ceased altogether. The absence of a rail system in the Cuyahoga Valley gave rise to a new age of agriculture and automobiles, characterized by a landscape dotted with small hamlets consisting of churches, gas stations, small stores and shops, and post offices which soon transformed into hubs for distant agricultural community members.

Preservation of the Valley Railway

Although industrial rail service came to an end in the Cuyahoga Valley, residents and visitors to the region were left with a sustainable and fully functional rail system that was still in working order. The following timeline describes the actions carried out by a group of determined railroad enthusiasts who focused their efforts on honoring the heritage of the Valley Railway.

- 1972: The Cuyahoga Valley preservation and Scenic Railway Association (CVPSR) is incorporated as a non-profit organization.

- 1975: Using the same locomotives which once carried freight and passengers, the CVPSR offers limited scenic rail excursions running the length of the Valley via steam-driven locomotives.

- 1987: The Cuyahoga Valley National Park (CVNRA) purchases the existing tracks from the Chessie System.

- 1988: CVNRA purchases its first diesel-powered locomotive.

- 1989: CVNRA formalizes an agreement with the Cuyahoga Valley Line (CVL) creating a partnership to offer improved excursion passenger service inside the park.

- 1991: CVL launches themed excursions and railroad-related events.

- 1994: CVL changes its organizational name to the Cuyahoga Valley Scenic Railroad (CVSR).

- 2007: CVSR expands its service to three daily excursions, Wednesday through Sunday.

- 2016: CVSR initiates a capital campaign.

- 2018: CVSR acquires four original California Zephyr train cars.

- 2019: Since 1989, a twenty-year, mutually beneficial partnership between the CVSR and the National Park Service exists to provide park visitors with the nation’s only not-profit heritage railroad which provides educational and entertaining programs.

- 2019: According to its 2017 and 2018 annual reports, the CVSR enjoys the support of 1700 volunteers and transports an estimated 200,000 passengers per year.

Photo by Sara Guren

[1] Sam Tamburro, Valley Railway Cultural Landscape Report (Draft), Cuyahoga Valley National Recreation Area, Technical Assistance and Professional Services Division.

References

- "Canals," Inland Navigation: Connecting the New Republic, 1790-1840, (Janet Haven, University of Virginia)

- The Ohio and Erie Canal (Ohio History Central)

- Captain Pearl R. Nye: Life on the Ohio and Erie Canal (Collection at Library of Congress)

- History of American Railroads (student project, Stanford University Computer Science)

- The Beginnings of American Railroads and Mapping (Library of Congress)

- Breakdown From Within: Virginia Railroads during the Civil War Era. Larry E. Johnson, University of Louisville

- Railroads of the Confederacy

- Railroads in the Civil War

- Financing Invention During the Second Industrial Revolution: Cleveland, Ohio, 1870-1920 (National Bureau of Economic Investment Working Paper)

- http://www.clevelandstoryteller.com/blog/2009/08/cleveland-the-heart-of-the-industrial-revolution/

- https://case.edu/ech/articles/i/industry

- http://web.ulib.csuohio.edu/speccoll/cdl/subj.html#e