The War of 1812 was unpopular among many, including Federalist-leaning clergy, who saw any association with France as leading to the downfall of the new country.

Was there ever a war so unreasonable, so wicked, so abominable? Minister Elisha Parish, Byfield, Massachusetts, April 1813.

David Osgood, A solemn protest against the late declaration of war, in a discourse, delivered on the next Lord's day after the tidings of it were received (Cambridge, Mass: Hilliard and Metcalf, 1812), 8.

Elijah Parish, a Federalist minister in Massachusetts, had strong feelings about America’s involvement in the War of 1812. By declaring war against the British, he intoned in a sermon, the Republicans had scandalously put the young country on the side of the “Anti-Christ” Napoleon and France. It was not the first time Parish had invoked such imagery. During President Jefferson’s efforts to wage economic warfare against the British—actions which proved particularly devastating to the New England economy—Parish complained that Jefferson’s efforts were driving America dangerously toward France, a country he described as “filled with violence.”

For religious dissenters like Parish, the roots of opposition were often ideological ones. It was not just the death and destruction that open war against Britain would bring. For many clergy, the more profound threat was aligning America with France—a nation whose bloody revolution and warfare had left many Americans with the belief that the French had a unique penchant for violence. Many clergy took the lead in fanning American fears, arguing that aligning with France would destroy the vulnerable young republic. In such Federalist ministers’ views, the mere “touch of France” was “pollution,” and its “embrace” a path towards death.

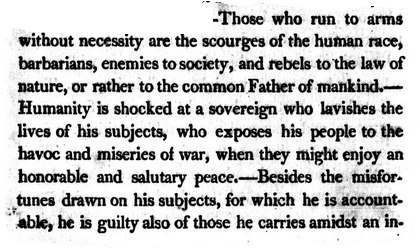

During the War of 1812, outspoken clergy created new precedents for dissent. Opponents of the war fought the notion that Americans must remain unanimously in support of presidential policies in wartime. The Federalist Timothy Dwight, who had served as a chaplain during the American Revolution, was a particularly frank critic of the expectation that the clergy fall in line with official policy. As Dwight put it, “men are not bound to obey magistrates acting contrary to the will of God and the scriptures.” Dwight attacked not just the architects of the war but their followers, as well. In bitter language, Dwight held that the “moral putrefaction” of the War of 1812 made soldiers themselves “murderers,” and should be recognized as evidence of the moral decay of America.

Last updated: March 22, 2016