Last updated: February 28, 2018

Article

Charles A. Longfellow in the Civil War

Charley’s First Taste of War

Charles Appleton Longfellow, known as Charley, was sixteen years old when the Civil War broke out in April 1861. At home in his famous father's house in Cambridge, Massachusetts, he saw the political turmoil of the conflict, but was isolated from the war to the south.

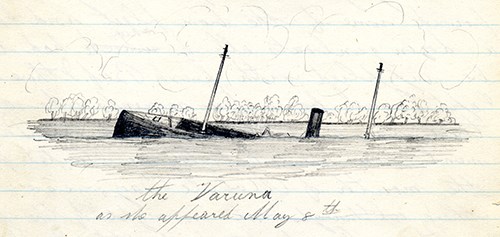

Charley’s first real exposure to the war came in the spring of 1862 when he and his friend William Pickman Fay set sail on the ship Parliament, owned by Fay’s father. Their destination was Ship Island, located in the Gulf of Mexico off the coast of Mississippi.

Charles Appleton Longfellow Papers, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters NHS

During the cruise Charley kept a journal in which he recorded the things he saw and did. One particular point of excitement occurred when the Parliament took on board a group of Confederate prisoners, and Charley was detailed to a watch, guarding over them. Armed with a cutlass and a pistol, Charley recorded “I poked round in the night among the prisoners to se [sic] if all was quiet if not I am to shoot them if I am not afraid to …”

Charley’s trip ended with his return to Boston on May 23, about two and a half months after his departure. His journal concludes, “Thus ended my first cruise and there never was a more successfull [sic] or pleasant cruise taken by any one.” His first foray into sailing, and the war, seemed to suit him.

Longfellow Enlists

With no particular interest in school or a conventional career, Charley’s thoughts for the next year must have often turned to the war. He would have seen or heard of many of his contemporaries, wealthy Bostonian Yankee sons such as Charles Russell Lowell, Jr., Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., and Robert Gould Shaw, leaving home to join the war effort and fight for the Union. Finally, in March 1863 the lure of action proved too much for Charley, and he left home unannounced to travel to Washington D.C. and join the Union army. Charley informed his father of his decision in a letter mailed from Portland, Maine by an accomplice:

Dear Papa

You know for how long a time I have been wanting to go to the war I have tried hard to resist the temptation of going without your leave but I cannot any longer, I feel it to be my first duty to do what I can for my country and I would willingly lay down my life for it if it would be of any good God Bless you all.

Yours affectionately

Charley.

Charley made his way to Washington, D.C. where he attached himself to an artillery regiment, Battery A of the 1st Massachusetts Artillery. The battery’s commanding officer, Captain W.H. McCartney, soon realized whose son Charley was, and as a result Charley’s time as an enlisted artilleryman was to be very short.

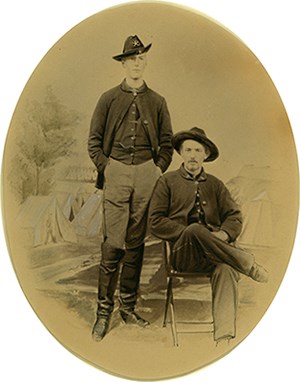

Museum Collection, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters NHS (LONG 14050)

Promotion

In letters home to his father, Charley professed satisfaction and happiness with his role as an enlisted man in an artillery unit, but the family name and connections were quickly put to use in an attempt to elevate Charley’s station in the army. Henry Longfellow wrote to friends, including Senator Charles Sumner, to see if a commission could be obtained for his son.

Within two weeks of his arrival at camp, Charley was offered a commission as a second lieutenant in the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry. Exactly what led to this offer is unclear, but Charley’s aunt Harriot "Hatty" Appleton was at this time engaged to Greely Stevenson Curtis, who happened to be a Lieutenant Colonel in the regiment. Charley himself expressed the thought that this family connection was responsible for the opportunity, stating in a letter to his father, “I suspect that my dear little “aunty” is at the bottom of this commission.”

The commission was formally granted on April 1, and Charley moved to his new regiment’s camp. He quickly set about learning the business of being a cavalry officer and acquiring all the necessary trappings, including horses, saber, pistol, uniform and sundry other items, costing his father almost $800.00 in the process. Charley was now officially in the army, and it would not be long before he was sent out into the field.

First Campaign

A couple of weeks after Charley joined the cavalry, the Union army moved out of its encampments and started a campaign that would culminate in a resounding defeat at Chancellorsville. Charley’s regiment spent most of its time guarding supply wagons and did not see combat. The highlight of his first few weeks in the field appears to have been a full speed ride through the town of Warrenton, Virginia, where the only opposition was “two fair ones in bathing hats who were seated on their piazza making faces at us and making signes [sic] as if we were running away.”

For the remainder of May and the beginning of June, 1863 Charley stayed in camp. He had earlier been appointed regimental adjutant, and now in addition to the regular drill and maintenance of camp life, he was also burdened with paperwork. Charley was not pleased with life in camp, and desired to be out in the field again. On May 10 he wrote, “It was mighty stupid coming [sic] back to this camp again, it is ten times as pleasant to be in the field on the march.”

Before he would get a chance to get back in the field, Charley would be laid low by an enemy far more deadly than any rebel bullet or saber cut, disease.

Camp Fever and Recovery

In early June, Charley fell ill with camp fever, a term used during the Civil War to encompass any number of illnesses, the most common of which were typhoid or typho-malarial fever. Upon receipt of the news that his son was ill, Henry W. Longfellow hurried down to Washington to attend to Charley. Henry spent two weeks in Washington helping nurse Charley back to health to the point where they could leave the city. During this time he and Charley received visitors, including Senator Charles Sumner and Dorothea Dix, who was at the time Superintendent of Army Nurses. It was while Charley was in a sickbed in Washington that his regiment saw its first serious action at the Battle of Aldie. Despite the fact that the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry was roughly handled and lost almost two hundred men, Charley was angry at the missed opportunity for glory on the field of battle.

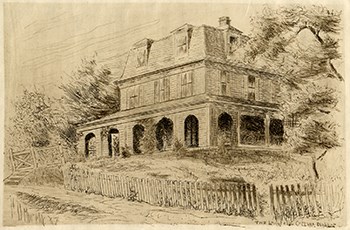

Museum Collection, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site (LONG 36357)

Charley was given medical leave and returned to Massachusetts with Henry. They reunited with the rest of the family at their cottage in Nahant in the hope that the environment there would help Charley’s recovery.

He spent all of July and half of August in Nahant before returning to army life. During this time he sunbathed, swam, yachted, and spent time with family and friends. On August 14, Charley departed Nahant and headed back to the war in Virginia.

Museum Collection, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site (LONG 4661)

Becoming A Veteran

Charley rejoined his regiment in Virginia and spent the rest of August pursuing rebel raiders, with little success. In September Charley first experienced heavy combat in action around Culpeper, Virginia. He wrote his father about his experience, detailing how the man next to him had a leg taken off by a bouncing cannonball and several other close shaves involving enemy artillery. The tone of Charley’s letter reveals a more serious appraisal of army life than he earlier exhibited, as in the closing paragraph of his letter he wrote, “they may talk about the gaiety of a soldiers life but it strikes me as pretty earnest work when shells are ripping and tearing your men to pieces.”

Charley spent the next couple of months on patrols, skirmishing with the enemy, foraging and drilling whenever he was encamped. He still looked forward to action and professed great satisfaction with the life of a cavalry officer. His chance would not come until late November, when the Union Army of the Potomac started to move against the Confederates in a series of maneuvers known as the Mine Run Campaign. It was during this campaign, near a small Virginia settlement named New Hope Church, that Charley Longfellow was at the forefront of the action, and had his military career cut short.

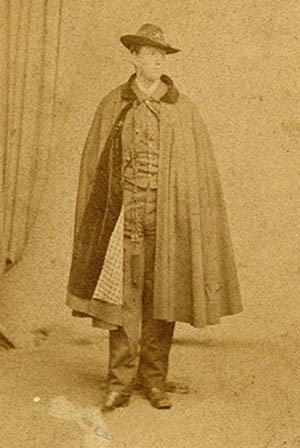

Museum Collection, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site (LONG 18791)

Wounded

In the confused skirmishing of the battle’s opening stages, Charley was shot through the back as he reconnoitered along the front lines. He was brought to New Hope Church, now serving as a field hospital, where the wound was inspected and dressed. Fortunately for Charley, the bullet did not lodge in his body, but passed through his back, nicking the spine on its way. He tersely recorded the event in his journal “got pluged [sic]”.

Charley spent four days recovering at New Hope Church, where Lieutenant Nathan Appleton, Jr., his mother’s half-brother, visited him. He then undertook an uncomfortable ride by wagon-ambulance and train to Alexandria, Virginia, where he was met by his anxious father and younger brother Ernest. Henry W. Longfellow had rushed from Cambridge to Washington as soon as news of Charley’s wounding was received (the telegram inaccurately reported that Charley was severely injured in the face). He then set about trying to locate Charley, and even obtained a military pass allowing him to go through army lines into Virginia to search for his wounded son.

After Charley had a few days in bed to gather strength for the trip home, the Longfellows left Washington by train on December 8, arriving in Boston late the following evening. Charley was fed, inspected by the family’s doctor, and put to bed. His part in the war was over.

Museum Collection, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters National Historic Site (LONG 4201)

Aftermath

Charley’s wound took considerable time to heal. Over a month after returning home, he still needed help getting dressed. He was impatient to get back to his unit and the war, but that would not come to pass. Much to his surprise, Charley was honorably discharged on February 15, 1864 “on account of physical disability”. He made some noise about returning to the army, possibly even as an enlisted man if he could not secure another commission, but ultimately he became accustomed to the idea of being a civilian once again.

Charley kept in touch with friends made during his brief career as a soldier, receiving letters and photographs from them and creating a scrapbook of newspaper articles relating to his unit’s role in the war. Although he never achieved the martial glory he dreamt of, by all accounts he had been a competent soldier and had more than a bit of luck to come home in one piece after suffering from a potentially fatal disease and a bullet wound that came within a hair’s-breadth of killing him.

Late in 1864, Charley sailed to Europe and entered a new phase of his life, that of a world traveler. He spent his remaining years visiting far-flung corners of the globe, including India, Japan, South America and the South Pacific. He passed away in the family home on Brattle Street in 1893 after a lengthy illness.