Historians debate the importance of the various causes of the War of 1812. While President James Madison did not cite the conquest of British Canada as a reason for declaring war, there is no doubt that it was a fundamental objective. Likewise, fear of King George III’s agents influencing Aboriginal peoples to resist settler expansion in the “Old Northwest” emerged as an understated factor.

It was convenient for Americans to blame the King’s agents for frontier troubles rather than look to their own actions in taking Aboriginal lands and in oppressing the Native population.

From Carl Benn, Native Memoirs from the War of 1812: Black Hawk and William Apess

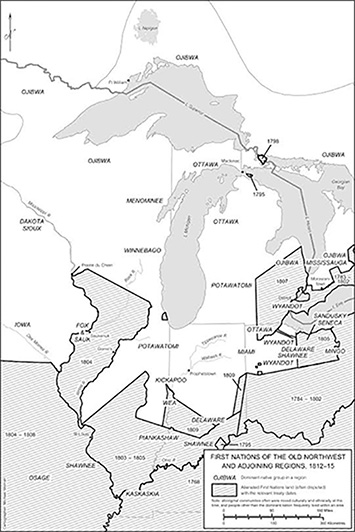

Britain, already fighting Napoleonic France, did not want hostilities with the United States. Consequently, its government made numerous concessions to the Americans prior to the war over tensions between the two countries within the limits of its strategic imperatives to defeat its European enemy who threatened the freedom of the island kingdom. Yet, British subjects in Canada had enjoyed long-standing associations with Aboriginal peoples in the Old Northwest through trade, family, and alliance relationships. These individuals – often in government employ – were sympathetic to the Shawnees, Potawatomis, Ottawas, and others who worried about their future in the face of large-scale land losses and the violence and degradations Natives suffered at the hands of American officials and settlers. Thus, people in British territory understood the growing militancy of individuals like Tecumseh, Tenskwatawa, and the other members of the Western Tribal Alliance that had begun to form in 1805. Crown officials also provided advice and supplies, including firearms that could be used for hunting or for war. Nevertheless, they tried to restrain the tribes from engaging in hostilities before 1812. They knew that a conflict between the United States and the Indigenous people near Canada’s borders could provide Washington with a reason or a pretext for marching into the colonies. At the same time, the British nevertheless worked to ensure that the Natives would ally with them if the U.S. invaded Canada. This was a fine line diplomatically, which some of the Republic’s leaders recognized but which most of its citizens did not. It was convenient for Americans to blame the King’s agents for frontier troubles rather than look to their own actions in taking Aboriginal lands and in oppressing the Native population. Harnessing anger directed towards both the Indigenous peoples and the British also was one way for those who wanted war with the United Kingdom to generate support for a military confrontation. Thus, accusations that the Crown’s agents had incited the tribes to violence became a cause of the War of 1812 even though that is not what the King’s officials had been doing.

The assessment above enjoys fairly widespread acceptance among scholars; yet a corollary to that story generally has been overlooked: the United States did not need to declare war on Great Britain in order to fight the Western Tribes, defeat them, and continue expanding into Native territories. (In fact, war between the Republic and the Western Tribes had broken out in November 1811, seven months before the Anglo-American conflict began.) If the Americans confined their war against the Aboriginal peoples within their own borders, the British would not have provided meaningful aid to the tribes, and certainly would not have sent troops to support them. It simply was not in their interests or the interests of their Canadian colonies to do so if they otherwise could avoid a military confrontation. Americans fought Natives before and after the War of 1812 without having to trigger a conflict with another Euro-American power. Most tellingly, the United States had waged war for control of the Ohio country in the 1790s, won the conflict, imposed a treaty on the defeated tribes, and acquired substantial quantities of land. At the time, the American government did not engage in a serious clash with Britain, despite threats to do so, even though the King’s soldiers and officials had taken a far more aggressive attitude towards supporting Natives within the Republic’s borders than they ever dreamt of doing in the years leading up to the War of 1812.

History is complex, and many of the assumptions we make should be reexamined. Asking penetrating questions about particular contexts, thinking about the broader circumstances that affected specific events, and approaching issues from new angles all enrich our understanding of the past. Such activities also make history more interesting – and useful – as we consider its legacies and our responses to them.

Last updated: August 15, 2017