Last updated: April 29, 2025

Article

Seeing Rock Markings in a New Way

NPS/Neal Herbert

When you retire, how would you like to spend your time? Golfing is one option, so is playing bridge. But how about volunteering at a national park? That’s what one retiree did, and his work changed the way we “see” rock markings.

In 2007, Bud Turner showed up at park headquarters in Moab looking for a volunteer opportunity that would allow him to contribute something to the park while experimenting with his passion for digital cameras, filters and different photographic techniques. He was especially interested in photographing prehistoric rock markings.

The park settled on Barrier Canyon Style rock markings as the subject of his project. This pictograph style is spectacular, and Canyonlands National Park contains a majority of known panels, including the Great Gallery in Horseshoe Canyon, the type site for the style. In many cases, the documentation of the panels was poor or non-existent, so the project had a great benefit to park managers. It was also potentially interesting to archeologists and amateur enthusiasts because there was very little hard science regarding dating, pigment compositions, and subtle stylistic differences.

Turner agreed to provide the park with a high-resolution photographic record of all the Barrier Canyon Style pictograph panels located in Canyonlands and in nearby Arches National Park. These digital and film images will be used as a baseline to help park managers determine the long-term effects of weathering and aging. The images also assisted researchers interested in investigating how the panels were created, what pigments and paint binders were used, and what changes to the panels were made by later artists. Selected images can also be used in educational displays to aid in the understanding and preservation of these important resources.

NPS/Bud Turner

In addition to the baseline record, Turner also photographed the panels in infrared wavelengths, and this is where things really become interesting. Rock marking pigments react differently in infrared wavelengths, which are invisible to the human eye, than they do in visible light. Our initial expectation was that lighter pigments, such as white, would become transparent, while darker colors, such as red, would become even darker, allowing the observer to see beneath a white outer layer of pigment to the darker image beneath. This would help reveal vandalized or eroded red pigments that could no longer be seen with the naked eye. What we have discovered, however, is that rock marking pigments don’t always follow expectations.

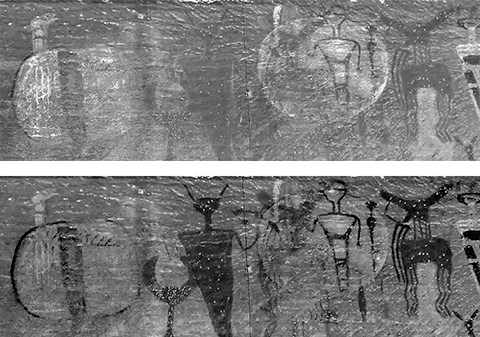

In the first set of pictures, the Courthouse Wash Panel at Arches National Park was photographed in both visible and infrared wavelengths. True to expectations, the white circular figures became transparent in the infrared wavelengths and the red figures became much darker. The amount of detail that can be seen in the infrared image is striking when compared to what can be seen in visible light.

NPS/Bud Turner

The second set of photos, however, confounded our initial expectations. The pigments at the Peekaboo Panel at The Needles did not react as expected to the infrared wavelengths. The white images did not become transparent and the red images did not get darker and more visible. However, some details became much more visible, such as the large trapezoidal figure in the upper right of the panel.

Turner’s contribution allowed us to “see” just how little we understand about the processes prehistoric people used to turn minerals into paint. Pigment composition is only one of the facets of these fascinating creations areas we hope to research in the future.

Turner's work was completed in 2007 thanks to a Discovery Pool Grant from the Canyonlands Natural History Association.

More Topics From Around the National Park System

Tags

- arches national park

- canyonlands national park

- american indians

- tribal relations

- archeology

- archaeology

- photography

- research

- canyonlands national park

- arches national park

- partnerships

- rock art

- volunteer

- art

- native american history

- american indian history

- horseshoe canyon

- culture

- baseline documentation

- documentation

- native americans

- history