In 2014, 124 sea turtle nests (122 loggerhead nests, and 2 green nests) and 104 false crawls were documented at Cape Hatteras National Seashore (CAHA). The first nesting activity was documented on May 26 and the last nesting activity was documented on September 6. Mean hatch success for all nests was 50.9% while mean emergence success was 44.8%. A total of 219 stranded sea turtles were documented within CAHA in 2014.

Introduction

Five species of sea turtles can be found in CAHA– the loggerhead (Caretta caretta), green (Chelonia mydas), leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea), hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata), and Kemp’s ridley (Lepidochelys kempii). In the 1970’s, the Leatherback, Kemp’s Ridley, and Hawksbill were listed under the Federal Endangered Species Act (ESA) as endangered and the Loggerhead as threatened. The Green population that nests in the Northwest Atlantic was listed on July 28, 1978, and is designated as threatened.

Non-breeding sea turtles of all five species can be found in the near-shore waters during much of the year (Epperly 1995). CAHA lies near the extreme northern limit of nesting for four of the five sea turtle species, including the Loggerhead, Green, Kemp’s Ridley and Leatherback. Hawksbill sea turtles are not known to nest at CAHA, but are known to occur here through strandings. The occasional Kemp’s Ridley nest has been documented in North Carolina over the past five years and in 2011 CAHA documented its first Kemp’s Ridley nest.

CAHA has been monitoring sea turtle activity since 1987 and standard operating procedures have been developed during this time. This report summarizes the monitoring results for 2014, comparisons to results from previous years, and the resource management activities undertaken for turtles in 2014. CAHA follows management guidelines defined by the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission (NCWRC) in the Handbook for Sea Turtle Volunteers in North Carolina, species recovery plans, and the Cape Hatteras National Seashore Off-Road Vehicle Management Plan and Special Regulation (ORV Management Plan).

ORV Management Plan

On February 15, 2012 the ORV Management Plan was enacted at CAHA. It was developed from 2007-2012 and included a special regulation detailing requirements for off- road vehicle (ORV) use at CAHA. A copy of the ORV Management Plan and other related documents are available electronically at https://parkplanning.nps.gov/caha. It includes establishment of an ORV permit system to drive on CAHA beaches. It also establishes survey times, frequency and buffer requirements for sea turtle nests and hatchlings. This was the third year the ORV Management Plan guided the management of protected species, including sea turtles, at CAHA.

The Record of Decision indicates that CAHA will "conduct a systematic review of data, annual reports, and other information every five years, after a major hurricane, or if necessitated by a significant change in protected species status (e.g. listing or de-listing), in order to evaluate the effectiveness of management actions in making progress toward the accomplishment of stated objectives". As part of the Reporting Requirements of the Biological Opinion (BO) for the Off-road Vehicle Management Plan (November 15, 2010), "an annual report detailing the monitoring and survey data collected during the preceding breeding season (as described in alternative F, in addition to the additional information required in the …Terms and Conditions) and summarizing all Piping Plover, Seabeach Amaranth, and sea turtle data must be provided to the Raleigh Field Office by January 31 of each year for review and comment".

In the November 15, 2010 BO, the USFWS determined that the level of anticipated take is not likely to result in jeopardy to the loggerhead, green, or leatherback sea turtle species. Through the actions taken by the resource management staff, CAHA has complied with the reasonable and prudent measures that are necessary and appropriate to minimize the take of sea turtles at CAHA. Protection was provided to sea turtles that came ashore to nest, incubating nests were monitored and protected, and emerging hatchlings were provided protection from ORVs. Proposed activities and access to nesting sea turtles, incubating turtle nests, and hatching events were timed and conducted to minimize impacts on sea turtles and sea turtle productivity. Resource management staff also responded to stranded sea turtles and coordinated the transport and delivery of live strandings to appropriate rehabilitation facilities. The non-discretionary terms and conditions for sea turtles were also met by providing the USFWS with this annual report. This annual report summarizing monitoring efforts and data collected during the 2014 breeding season and aids in fulfilling the reporting requirements of the November 15, 2010, BO.

Cooperating Agencies

CAHA cooperates with the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), and NCWRC on sea turtle protection. All nesting activity and stranding reports are reported to the North Carolina Sea Turtle Program Coordinator at NCWRC through the seaturtle.org website. An annual permit is issued to CAHA by NCWRC under the authority of the USFWS for the possession and disposition of stranded marine turtles and relocation of nests.

Methods

Nesting Activity

Monitoring for sea turtle nesting activity began on April 30, 2014. Patrols utilizing a UTV (or 4X4 truck during inclement weather) were conducted in the morning, beginning approximately at dawn. Each nesting activity was recorded as either a false crawl or nest. All nests were confirmed by locating eggs at the nest site. One egg was taken from each clutch for research purposes. The decision to relocate the nest or for the nest to remain in situ was made at the time of nest discovery. If no eggs were laid, the nesting activity was considered a false crawl and recorded by collecting a GPS point at the apex of the crawl. All sea turtle “activities” were reported to NCWRC using the Sea Turtle Nest Monitoring System (STNMS) through the Seaturtle.org website.

All nests were protected from human disturbance by initially installing a 10 x 10 meter signed area around the nest site. At day 50 – 55 of incubation, an expanded closure beginning approximately 10 meters behind the nest and extending to the water line was installed, varying in width from 25 to 105 meters. This closure protected the nest site and hatchlings from human disturbance during hatching events. Each nest site was checked daily in order to document any disturbances or hatching events.

Approximately three to five days after an initial hatching event, nests were excavated and closures were removed. Resource management staff collected required data to determine hatch and emergence success for each nest excavation. Live hatchlings discovered upon excavation of the nest were collected and released at or after dusk the same day. Monitoring efforts to locate new nests ended Sept 26, 2014.

Stranding Activity

A stranded turtle is a non-nesting turtle that drifts to shore either sick, injured, or dead. Data was collected for each reported or observed stranding. Whenever possible, further data was collected by performing a necropsy on dead strandings. Live stranded turtles were transported to a facility for treatment and recovery. All data was reported to NCWRC using the Sea Turtle Rehabilitation and Necropsy Database (STRAND) through the seaturtle.org website.

An increased effort to locate stranded turtles began in early November and continued throughout the winter due to the increased chance of “cold stunned” turtles. Searches for cold stunned turtles occurred primarily on sound side shorelines of CAHA, where the majority of cold stunned turtles have been found in the past. Cold stunning refers to the hypothermic reaction that occurs when sea turtles are exposed to prolonged cold water temperatures. Initial symptoms include a decreased heart rate, decreased circulation, and lethargy followed by shock, pneumonia and possibly death (from http://www.nero.noaa.gov/prot_res/stranding/cold.html).

Results

Nesting

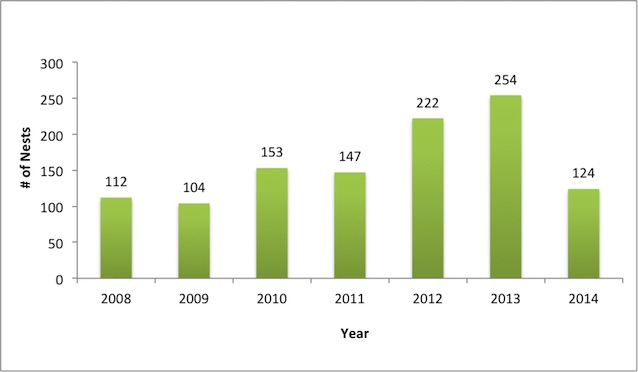

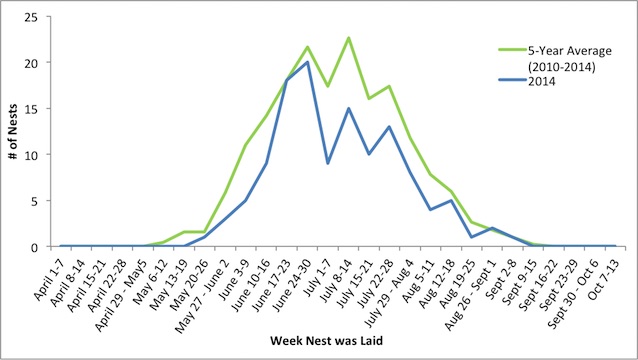

A total of 124 nests (122 loggerhead nests, and 2 green nests) were observed at CAHA in 2014. Of the confirmed nests, 2 (1.6%) were found on Bodie Island, 80 (64.5%) on Hatteras Island, and 42 (33.9%) on Ocracoke Island (Appendix B, Maps 1 – 4 and Appendix C). This was the fewest nests recorded at CAHA in a single nesting season (Figure 1) since 2009. The first recorded nest for the 2014 season occurred on May 26 and the last nest was recorded on September 6. While nesting occurred throughout this period, peak nesting occurred from June 24 – 30 (Figure 2).

Figure 1. CAHA sea turtle nest numbers 2008–2014.

Figure 2. Number of nests by lay date for 2014 and average of previous five years.

Nest Relocation

Of the 124 nests, 33 (26.6%) were relocated (Appendix A). Most nests were moved due to natural factors including location of nest at or below high tide line or the nest was laid in an area susceptible to erosion. Relocation methods recommended by NCWRC, found in the Handbook for Sea Turtle Volunteers in North Carolina (2006), were followed.

False Crawls

During the 2014 breeding season, 104 false crawls (aborted nesting attempts) were recorded. False crawls accounted for 45.6% of the 228 total turtle activities. Of the 104 false crawls, 1 (1.0%) was documented on Bodie Island, 57 (54.8%) on Hatteras Island, and 46 (44.2%) on Ocracoke Island (Appendix B, Maps 5 – 8, and Appendix D). There was one documented green sea turtle false crawl, while loggerhead sea turtles accounted for the remaining 103 false crawls.

Hatching

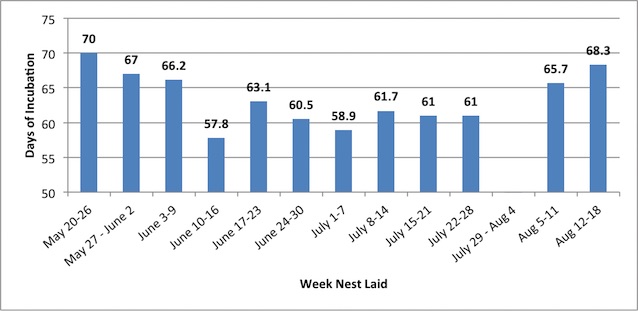

In 2014, the mean clutch count was 105.3 eggs per nest (Table 1 and Appendix A). The mean clutch count was determined using total egg counts at the time of relocation from relocated nests only. Average incubation period of nests with known lay and emergence dates was 62.2 days (Table 1 and Appendix A). Incubation periods depend mostly upon sand temperature (Bustard and Greenham 1968) and ranged from 53 days to 74 days (Figure 3). Some emergences went undetected due to rain, wind, tides and storm events.

Table 1. Sea turtle hatch summary 2008-2014.

|

Year |

Nests |

Avg. Clutch |

Average Incubation (days) |

EMR% |

|

2008 |

112 |

109.0 |

59.7 |

52% |

|

2009 |

104 |

114.9 |

65 |

31% |

|

2010 |

152 |

110.9 |

57 |

48% |

|

2011 |

147 |

115.8 |

58 |

48% |

|

2012 |

222 |

105.3 |

60.1 |

73% |

|

2013 |

254 |

116.9 |

62.3 |

56% |

|

2014 |

124 |

105.3 |

62.2 |

45% |

Figure 3. Average incubation days of nests by week nest was laid (2014).

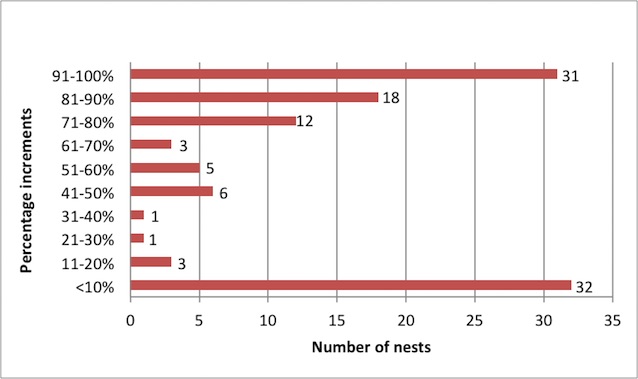

Figure 4. 2014 Nest hatch success percentage totals, broken down by 10% increments.1

1 12 of 124 nests were lost to significant storm and tide events and were not included in Figure 4.

Mean emergence success was calculated by taking the unweighted mean of all the individual nest emergence successes. Emergence success is the total number of hatchlings that emerged unaided from the nest cavity, relative to the total number of eggs in the nest. Any hatchlings found during excavations were not considered to have emerged. Mean emergence success for 2014 was 44.8% (Appendix A). Mean hatch success was calculated by taking the unweighted mean of all the individual nest hatch successes. Hatching success is the percentage of eggs in a nest that produce hatchlings. Any hatchlings found during excavations, live or dead, were considered hatched. Mean hatch success for 2014 was 50.9% (Appendix A). A total of 31 nests had >91%, 18 nests had 81-90%, 12 nests had 71-80%, 3 nests had 61-70%, 5 nests had 51-60%, 6 nests had 41-50%, 1 nest had 31-40%, 1 nest had 21-30%, 3 nests had 11-20%, and 32 nests had <10% hatching success (Figure 4).

Storm, Tide and Overwash Loss

During the 2014 sea turtle nesting season 12 nests were washed away by significant storm and tide events (Appendix A). Hurricane Arthur washed away six, Hurricane Bertha washed away one, a new moon tide event combined with >20 mph northeast winds washed away two, Hurricane Cristobal washed away one, and Hurricane Edouard washed away two nests. In addition, 34 of the 36 nests with a hatch success rate ≤ 30% were significantly impacted by these storms (Figure 4). Excessive water inundation, overwashes, sand accretion, and sand loss over the top of these nests were contributing factors to their poor hatch and emergence successes.

Strandings

In 2014, 219 stranded sea turtles were documented within CAHA (Table 2 and Appendix B, Maps 9 – 12). Volunteers associated with The Network for Endangered Sea Turtles (N.E.S.T.) assisted National Park Service staff by reporting and sometimes responding to observed strandings.

Table 2. Sea turtle strandings at CAHA by species, 2009–2014.

|

Year2 |

Stranding Totals |

Species Composition |

|||||

|

Loggerhead |

Kemp's Ridley |

Green |

Leatherback |

Hawksbill |

Unk. |

||

|

2009 |

297 |

53 |

57 |

183 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

|

2010 |

444 |

100 |

108 |

235 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

2011 |

148 |

50 |

46 |

49 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

|

2012 |

126 |

34 |

32 |

50 |

2 |

0 |

8 |

|

2013 |

189 |

38 |

52 |

94 |

1 |

0 |

4 |

|

2014 |

219 |

50 |

61 |

104 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

2 Total stranding numbers for 2008-2011 include some strandings that occurred outside of CAHA boundaries

Of the 219 strandings, 55 (25.1%) were found alive and transferred to the North Carolina Aquarium’s, Sea Turtle Assistance and Rehabilitation Center (STAR) on Roanoke Island or a similar facility for rehabilitation.

Efforts were made to necropsy dead strandings to determine possible cause of death, sex, any abnormalities, and to collect requested samples for ongoing research. Sex was determined in 98 strandings (69 female, 29 male). Samples collected during necropsies, including eyes, flippers, muscle, foreign debris, and tags, were provided to cooperating researchers. Probable cause of death, when possible, was determined by NCWRC (Table 3). During periods of cold water temperatures (7-10° C), sea turtles are most prone to stranding due to hypothermia (Spotilla 2004), which is often referred to as “cold stunning”.

Table 3. Probable cause of sea turtle strandings at CAHA by month, 2014.

|

Month |

No Apparent Injuries |

Cold Stun |

Other |

Watercraft |

Entanglement |

Pollution / Debris |

Disease |

Shark |

Unable to Assess |

Total |

|

January |

11 |

58 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

73 |

|

February |

3 |

10 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

16 |

|

March |

4 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

|

April |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

|

May |

17 |

0 |

2 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

4 |

27 |

|

June |

3 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

6 |

|

July |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

|

August |

3 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

8 |

|

September |

3 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

7 |

|

October |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

|

November |

12 |

9 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

26 |

|

December |

30 |

11 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

42 |

|

Total |

90 |

89 |

6 |

14 |

2 |

4 |

3 |

1 |

10 |

219 |

Of the 55 live stranded sea turtles taken to the North Carolina Aquarium on Roanoke Island’s (NCARI) STAR Center, 28 (50%) were successfully rehabilitated and released (Table 4). One of the deceased Green (Cm) sea turtles was a result of euthanasia. Six turtles (10%) remain in active rehab as of December 31, 2014. Only four turtles, all from Ocracoke, were transported to rehab facilities elsewhere due to the island’s proximity to nearby facilities via ferry.

Table 4. Disposition of 2014 rehabilitated sea turtles by species.

|

Disposition of 2014 Rehabbed Sea Turtles by Species |

||||

|

|

Cc |

Cm |

Lk |

Total |

|

Released |

4 |

20 |

4 |

28 |

|

Deceased |

2 |

6 |

9 |

17 |

|

Remain in Rehab* |

2 |

3 |

1 |

6 |

|

Unknown** |

3 |

0 |

1 |

4 |

* In rehab at NCARI as of December 31, 2014

** Turtles transported to rehab facility other than NCARI; no data available.

Discussion

Turtle Sense: Developing a Sensor to Detect Hatching and Emergence at Sea Turtle Nests

Cape Hatteras National Seashore collaborated with Thomas Zimmerman (IBM), Samuel Wantman (Nerds Without Borders-NWB), and Eric Kaplan (Hatteras Island Ocean Center-HIOC) for the second year, to develop a sensor that is placed in turtle nests to monitor movement and temperature fluctuations. The hope is to be able to correlate the measurements with hatching and emergence events. The above named individuals donated their technical knowledge and expertise and CAHA provided partial funding for the materials needed to build the sensors and installed the sensors in the field. The "Turtle Sense" project is still very much in its infancy and the Seashore was fortunate to be chosen as the pilot study area.

In 2013, the initial year of the study, four prototype sensors were deployed. The sensors were placed on top of the uppermost eggs at the time of nest discovery and then connected to communication towers closer to expected hatch time. Data collected by the sensors was transmitted every two hours and a computer model analyzed the data. The project got off to a late start and sensors were placed in late season nests. Unfortunately, none of the turtle nests that were being monitored hatched. Through the 2013 – 2014 offseason communication and design issues were addressed and the second phase of sensors and equipment were constructed from the above collaborators.

In 2014, the second phase of the study, 19 sensors were deployed during peak nesting and hatching season. All sensors installed into viable nests that hatched showed significant movement patterns as hatchings occurred throughout the season. Only one out of the 19 sensors malfunctioned and did not record any data. We still have a long way to go in the development of this project and it may take a few years and a number of trials to make sure that the sensors function properly and can be relied upon.

DNA Study

Since 2010, CAHA, along with all other North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia beaches, has participated in a genetic mark-recapture study of Northern Recovery Unit nesting female loggerheads using DNA derived from eggs. The study is coordinated by the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, the University of Georgia, and NCWRC. One egg from each nest is taken and sampled for maternal DNA. This allows each nest from North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia to be “assigned” to a nesting female. This research ultimately will answer questions about the total number of nesting females in the population, the number of nests each female lays per season, distance between nests laid by individual females, and other information that is important to understanding the population dynamics of sea turtles. Currently, the results of this study are preliminary and remain the copyright of the project coordinators.

Depredation

Opossum depredated one hatchling from one nest (Appendix A). No other mammalian depredation was documented, however tracks from mammalian predators (feral cat, dog, raccoon, mink, etc.) were observed at nest sites on mornings following hatching events.

Ghost crabs depredated 55 eggs from nine nests prior to nest excavations. Ghost crab depredation of 12 hatchlings from nine nests was also documented, but the full extent of hatchling depredation by ghost crabs is unknown. Observations were made of ghost crabs in the act of predating hatchlings. These observations occurred within nest cavities during excavations as well as after hatching events inside of ghost crab holes in the vicinity of the nest site.

Late Nest Management

A late nest refers to a nest that is laid on or after August 1 and incubates for longer than 90 days. In 2014, three nests fit these criteria. Mean hatch success for late nests was 0% and mean emergence success was 0%. Following NCWRC recommendations, after 90 days of incubation, an excavation began of the nests. If a viable embryo was observed, the excavation stopped and the nest was left in place. If hatching activity was not observed after 100 days of incubation, the closure extending to the water was removed and the nest site itself remained protected by a smaller closure. The eggs were then checked approximately every 10 days for viability. Nests were fully excavated when no viable embryos were observed.

Nesting Activity on Private Property Adjacent to CAHA

Superintendent’s Order #25 was effective beginning in May, 2013. This order established Park protocols which personnel implemented when sea turtle nesting activity was observed on private property. In these instances, property owners were contacted in order to request access to their property for data collection and to carry out possible protection measures. This season, three sea turtle nests were discovered to have been laid on private property within the villages on Hatteras Island. One of these nests was observed on private property 0.46 mi North of Rodanthe Pier. The property owner was contacted and allowed NPS staff to leave the nest in situ and hatch following NPS protocols. The remaining two nests were observed by North Carolina Department of Transportation (NCDOT) staff and relocated by NPS employees to CAHA property (please see “NCDOT Patrol” below). Data was able to be collected for all activities and is included in this report.

NCDOT Patrol

The northern limit where NPS staff patrolled for sea turtle activity extended to 100 meters beyond the Rodanthe pier. Using GIS software, it was determined that this location marks the boundary where US Government property and private property meet. Most of the remaining stretch of beach was patrolled by NCDOT beginning at Sea Oats Drive and extending to Mirlo Beach, where Rodanthe meets Pea Island NWR. NCDOT patrolled this area for the entire 2014 nesting season as mandated by protocols from the Beach Renourishment Project that has taken place this year. Two sea turtle activities (two nests) were documented by NCDOT. As per protocol, the nests were re-located to safer sections of beach on CAHA property at 0.17 mi South of Ramp 27 and 0.07 mi South of Ramp 23.

Incidental Take / Human Disturbance

All species of sea turtles nesting at CAHA are protected under the ESA of 1973. Under the ESA, “take” is any human induced threat to a species that is listed. Take is defined as “to harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, capture or collect, or to attempt to engage in any such conduct.” Harm is further defined to include significant habitat modification or degradation that results in the death or injury to listed species by significantly impairing behavioral patterns such as breeding, feeding, or sheltering. It is unknown to what extent human activities disrupted sea turtle nesting activities during the 2014 nesting season. People on the beach at night can disturb female turtles during the egg laying process. From the time a female exits the surf until she has begun covering her nest, she is highly vulnerable to disturbance, especially prior to and during the early stages of egg laying. Much of CAHA’s shoreline remains open to pedestrians and CAHA staff is unable to monitor the entire shoreline for nesting turtles 24 hours a day. CAHA minimized some of these effects by closing the shorelines to non-essential ORV use from 9:00 p.m. until 7:00 a.m. to provide for sea turtle protection.

Closure Violations

Closure violations are documented whenever possible by resource management staff. A total of 48 pedestrian violations of turtle closures were documented. A total of 12 dog, three cat, and eight ORV violations were also documented. No direct loss of eggs or hatchlings was documented due to a closure violation.

Artificial Lighting

This year, misorientation (directed movement of a hatchling towards an inappropriate object or goal) or disorientation (lack of directed movement towards a specific area or goal) was documented at one nest, resulting in the death of 2 hatchlings (Appendix A). Another eight live hatchlings were observed to be affected by the same artificial ambient lights. These hatchlings were collected and released into the water.

Since the majority of nests are not observed during hatching events, the extent of hatchling loss due to artificial lighting is unknown. Artificial light is known to disturb nesting females and disorient hatchlings. Outdoor lights, beach fires, and headlights may deter nesting females from laying their nests along stretches of optimal beach. Hatchlings use natural light to navigate toward the water. When artificial lights are brighter than the natural light reflecting off the surface of the ocean, hatchlings will become disoriented and crawl away from the shoreline and toward these brighter lights and the dunes. This causes hatchling mortality due to exhaustion and increased chance of predation.

CAHA continues to try and decrease the effects of artificial lighting on sea turtles. Since 2005, black silt fencing has been utilized around most turtle nests to decrease the amount of artificial light shone onto the beach, thereby decreasing the negative effects of light on hatchlings. In 2012, a Superintendent’s Order was established that sets outdoor lighting guidelines within CAHA boundaries. In the 2013 season, CAHA staff worked with cooperating agencies on an educational public outreach campaign focusing on the effects of artificial lighting on sea turtles. Brochures and light switch stickers were printed and dispersed to the public as well as placed in many rental homes on Hatteras Island. This season, CAHA staff continued their efforts to educate the public on artificial lighting by dispersing brochures to the public at sea turtle nests due to hatch. Efforts were also made to encourage vacationers at their rental homes to shut off all artificial lighting not being used during nighttime hours.

The ORV Management Plan regulates off-road night driving, which has the potential to decrease disturbance from headlights on nesting female turtles and hatchlings. Night driving was prohibited from May 1 through September 15 from 9:00 p.m. to 7:00 a.m. Starting September 16, night driving was systematically re-opened as nests were excavated and closures removed. Starting November 25th, night driving was not restricted due to nests.

Recreational Beach Items

Recreational beach items (i.e. shade canopies, furniture, volleyball nets, etc.) that remain on the beach at night can cause turtles to abort their nesting attempt (NMFS, USFWS 1991). These items can cause a visual disturbance for nesting turtles and/or can act as a physical impediment. During the 2014 nesting season resource management staff continued to tie notices to personal property found on the beach after dawn, advising owners of the threats to nesting sea turtles as well as safety issues and National Park Service (NPS) regulations regarding abandoned property. Efforts were made by beach roving NPS staff to contact and educate visitors of the issues concerning property left on the beaches overnight. Items left on the beach 24 hours after tagging were subject to removal by NPS staff.

References

Bustard, Robert H. and Greenham, P. 1968. Physical and chemical factors affecting hatching in green sea turtle, Chelonia mydas (L.). Ecology, Vol. 49, No. 2, pp. 269-276.

Epperly, Sheryan P., Braun, J., and Veishlow, A. 1995. Sea turtles in North Carolina waters. Conservation Biology, Vol. 9, No. 2, pp. 384-394.

National Marine Fisheries Service and Fish and Wildlife Services. 2008 Recovery Plan for the Northwest Atlantic Population of the Loggerhead Sea Turtle. Washington, DC: National Marine Fisheries Service.

National Park Service. 2010. Cape Hatteras National Seashore Off-Road Vehicle Management Plan and Environmental Impact Statement. U. S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Cape Hatteras National Seashore, North Carolina.

North Carolina Wildlife Resource Commission. 2006. Handbook for Sea turtle Volunteers in North Carolina. Raleigh, NC: North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission.

Spotilla, James R. 2004. Sea Turtles: A Complete Guide to their Biology, Behavior, and Conservation. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2010. Biological Opinion the Off-Road Vehicle Management Plan for Cape Hatteras National Seashore, Dare and Hyde Counties, North Carolina. U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Raleigh Field Office, Raleigh, NC. 156 pp.

Appendix A. 2014 Project Summary Report/Guide for CAHA Sea Turtle Nests

Sea Turtle Nest Monitoring System Project Summary Report

|

Survey N Boundary |

Ramp 1, Bodie Island (excludes Pea Island NWR) |

|||

|

Survey S Boundary |

South Point, Ocracoke |

|||

|

Length of Daily Survey (km) |

104 km |

Total Kilometers Surveyed |

15600 |

|

|

km = miles x 1.6 |

||||

|

Total Days Surveyed |

150 |

Days per Week Surveyed |

7 |

|

|

Time of Day Surveyed |

Morning |

Number of Participants |

18 |

|

|

Date Surveys Began |

4/30/2013 |

Date Surveys Ended |

9/26/2013 |

|

|

Date of First Crawl |

5/7/2013 |

Date of Last Crawl |

9/06/2013 |

|

|

Date of First Nest |

5/26/2013 |

Date of Last Nest |

9/06/2013 |

|

|

Total Nests |

124 |

Undetected |

0 |

|

|

Nesting Density (nests/km) |

1.19 |

Disoriented/Misoriented |

1 |

|

|

In Situ |

91 |

Washed Away Tide/Storm |

12 |

|

|

Relocated |

33 (26.6%) |

Depredated |

16 |

|

|

False Crawls |

104 |

Unknown |

0 |

|

|

Mean Clutch Count |

105.3 |

Incubation Duration (All) |

62.2 |

|

|

Hatchlings Produced |

6988 |

Incubation Duration (In situ) |

62.4 |

|

|

Hatchlings Emerged |

6172 |

Incubation Duration (Relocated) |

61.8 |

|

|

|

||||

|

MEAN |

MEAN |

NEST |

BEACH |

|

|

50.90% |

44.80% |

58.0% |

54.3% |

|

|

IN SITU: 48.0% |

IN SITU: 44.0% |

IN SITU: 57.1% |

TOTAL NESTS: 124 |

|

|

RELOCATED: 58.9% |

RELOCATED: 47.0% |

RELOCATED: 60.6% |

TOTAL CRAWLS: 228 |

|

|

Eggs Lost (Total Eggs Lost = 255) |

||||

|

Research |

121 |

Ghost Crab |

55 |

|

|

Birds |

5 |

Tide / Storm |

50 |

|

|

Other |

19 |

Broken eggs |

5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hatchling Loss (Total Hatchling Loss = 23) |

||||

|

Misorientation |

2 (8 live) |

Ghost Crab |

12 |

|

|

|

|

Other (Opossum) |

1 |

|

For Appendix B, select the Sea Turtle 2014 Annual Report for Cape Hatteras Appendix B: Maps article.

Tags

- assateague island national seashore

- canaveral national seashore

- cape hatteras national seashore

- cape lookout national seashore

- gulf islands national seashore

- padre island national seashore

- cape hatteras

- cape hatteras national seashore

- sea turtle

- sea turtles

- sea turtle nest excavation

- wildlife

- wildlife research

- green sea turtle

- kemps ridley

- loggerhead

- leatherback

- hawksbill

- stranding

- nesting

- 2014

- natural resource annual report

Last updated: December 19, 2017