Last updated: October 27, 2020

Article

Building the District of Columbia War Memorial

“I send this contribution because I heard the Marine Band play ‘The Battle Hymn of the Republic’ in front of the Earle Theater the other evening, and because the music and the Spring twilight and the Marines brought back a lot of memories.”

An anonymous American veteran’s letter sent with a donation to build the District of Columbia War Memorial.

NPS

Description and Distinction

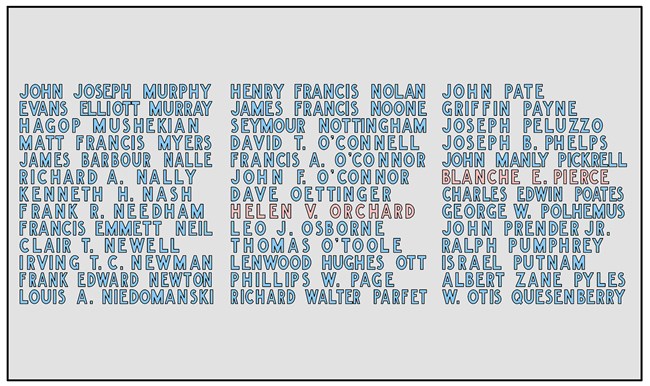

The District of Columbia War Memorial was built in 1931 to honor the more than 26,000 residents of Washington, D.C., who served in World War I. The memorial stands in West Potomac Park in a grove of trees between the Reflecting Pool and Independence Avenue. It is the only local monument in the immediate vicinity of the National Mall. A circular, open-air, Doric structure, it was designed with the purpose of being both a memorial and a bandstand, from which each concert would be a tribute to those who served in the war. With an overall height of 47 feet and a diameter of 44 feet, the D.C. War Memorial is considerably smaller than the other monuments on the Mall. It is built almost entirely of Vermont marble from a Danby, Vermont quarry. Twelve fluted columns support the domed roof. Each column is 22 feet in height and 3 feet 10 inches in diameter. The memorial stands on a 4-foot-high circular marble platform around which are inscribed the names of the 499 Washington residents who died in service during World War I. The names were inscribed on the face of the platform in alphabetical order with no distinction by rank, race, or gender; 7 of the 499 names are those of women

Commission of Fine Arts

A month after World War I ended common Americans started writing letters proposing ideas for a memorial to honor the 26,000 District of Columbia residents who served in the war. It would take a DC power family 13 years to bring the project to fruition. The effort would be wrapped up in things all too common in the nation’s capital: politics, red tape, and money.

Bandstands and Bureaucracy

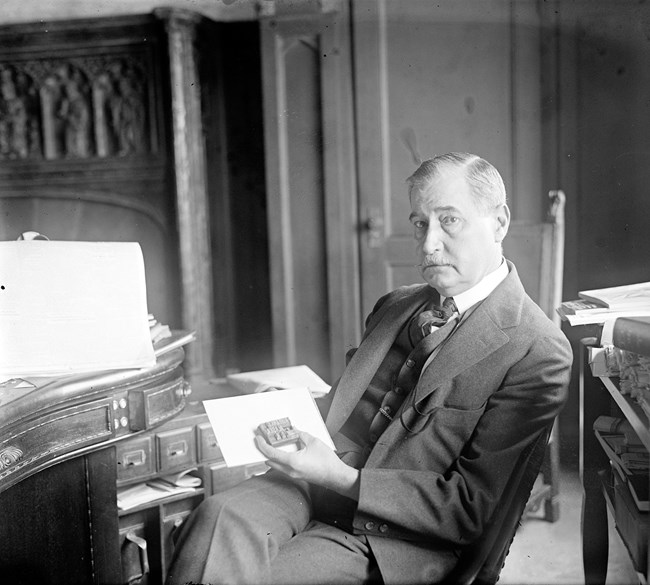

For a memorial in Washington, DC to have prominence it needed to be placed on federal land. By law, this required a design to be approved by the Commission of Fine Arts. A new memorial would also need to be funded by private sources. Frank B. Noyes and his wife Janet were the perfect couple to take on such a task. The Noyes family owned the Washington Evening Star newspaper. Frank founded and was president of the Associated Press. Janet was active in many civic organizations in Washington.

Numerous ideas for a war memorial were floated but Janet Noyes’ idea stuck. She proposed to replace an old wooden bandstand in West Potomac Park with a marble structure. The memorial would serve as a temple to the war dead and be a living memorial that hosted military bands. The idea caught on. The US Congress even put Janet’s desired location into the resolution approving the plan. However, before the planning and designing could begin in earnest, Congress would need to sanction official committees..

Library of Congress (LC-DIG-npcc-10826)

Fundraising and the Franchise

During the design of the memorial fundraising began. President Calvin Coolidge made one of the first donations and authorized the solicitation of funds in government offices. Despite these measures, fundraising was slow. A frustrated executive from the American Legion, Paul J. McGahan, criticized DC residents and the US Congress for not acting quicker to make the memorial a reality,

"Washington lags behind every State in the Union in expressing its appreciation of the services of its sons and daughters who ‘went to war’. Native Washingtonians have been hiding behind the cloak of Congress and Congress has not localized its treatment of veterans in the District of Columbia to the extent that is their due because of its paternal legislative relationship to the disenfranchised Capital City."

McGahan refers to Washingtonians as ‘disenfranchised’ since they were not represented in congress (and are still only represented by a non-voting delegate) and had no presidential electors. Poet John Clagett Proctor made the connection between DC resident’s war service and lack of voting rights just after the war’s in 1919,

“Let's get together, people, And everybody root,

That's how we whipped the Germans and The Austrians to boot —

Just with concentrated action, And no one can refute

That a lot can be accomplished Where all just follow suit.

We want a representative — On this we are agreed —

Some one to sit in Congress to Explain just what we need"

Frank Noyes’ brother Theodore advocated for a constitutional amendment to give DC citizens representation before the war. He lead the Citizens’ Joint Committee on National Representation for the District of Columbia. World War I slowed the campaign but it eventually succeeded in 1961, giving DC residents the right to vote for three presidential electors.

The fundraising campaign also succeeded, in early 1931.

Commission of Fine Arts

Construction and Community

The commission was ready to start construction. In a fit of community pride or nepotism, the president of the DC Chamber of Commerce, Harry King, stated, "Construction of the war memorial by out-of-town agencies would violate the principle and do injustice of the people of our city." Perhaps as a result, six local contractors submitted bids for the project by March 12, 1931. The memorial commission selected the lowest bidder, James Baird Co., Inc.

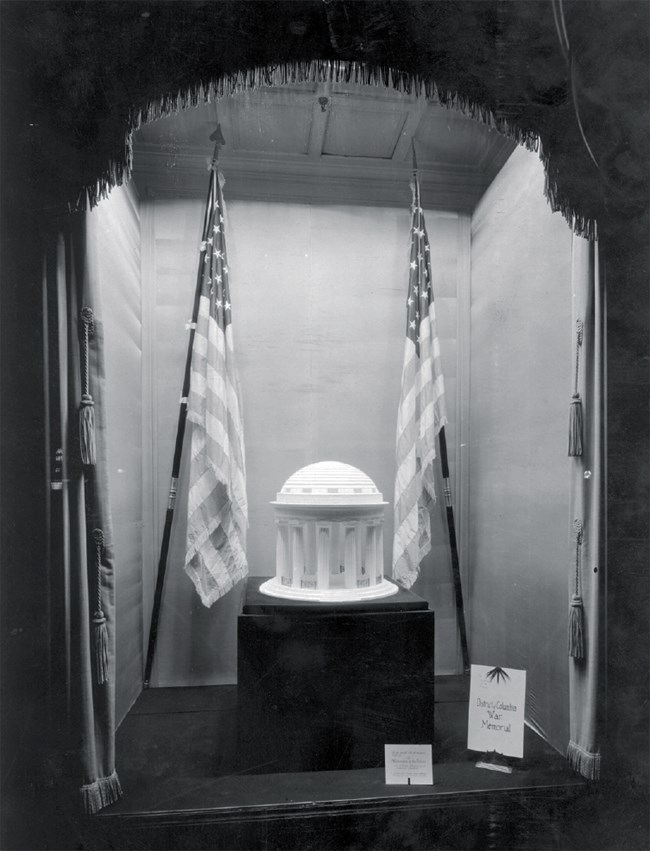

Other local DC institutions are wrapped up in the history of the war memorial project. The first model of the memorial was placed in the corner window at Woodward & Lothrop, locally known as “Woodies”. Dr. Frank W. Ballou, superintendent of schools, helped in the fundraising campaign. Today, Ballou is recognized as a high school in the Anacostia section of DC. The memorial campaign headquarters was located in the Gridiron room of the New Willard Hotel, still one of the most prominent hotels in DC today.

NPS

Friezes and Fairness

The original inscription on the frieze of the DC War Memorial read “In Memory of the Men and Women of the District of Columbia…” The March 1931 plans revealed that the wording was changed to read as it does today: “A Memorial to the Armed Forces from the District of Columbia Who Served Their Country in the World War.” Why the change from recognizing to obscuring gender? We don’t know. But we do know that men and women are recognized in the carvings at the base of the memorial. In a manner atypical for the era, the 499 names of the men and women are arranged alphabetically without regard to rank, race, or gender.Selecting the names inscribed on the monument was not easy. The American Legion’s list of the fallen service members included 536 names. Lists supplied by the US Army, Navy, and Marine Corps included 448 names. Adding to the confusion, 344 names appeared on one or the other list but not on both. Frank Noyes appointed a five-person committee to resolve the matter. In the end, a list of 499 names was compiled based on the following criteria: first, the person must have died while in active service prior to the official ending of the war, or the person must have been discharged because of a physical injury sustained during the war and died prior to November 11, 1918. Second, the person must have been an actual resident and citizen of the District of Columbia prior to his or her entry into the service. The service lists were verified by checking the names against War Department service cards. In addition, the lists were printed three times in local newspapers so that the public could supply suggestions and corrections.

Marches and Matrimony

The DC War Memorial replaced an existing bandstand. Why was it important to preserve this form? John Phillip Sousa.

Sousa was the most popular musician in the United States in the late 1800’s to the early 1900’s. His bands, the US Marine Corps Band then the Sousa Band played the pop music of the era, band music. A letter from Sousa endorsed Brooke’s design of the memorial,

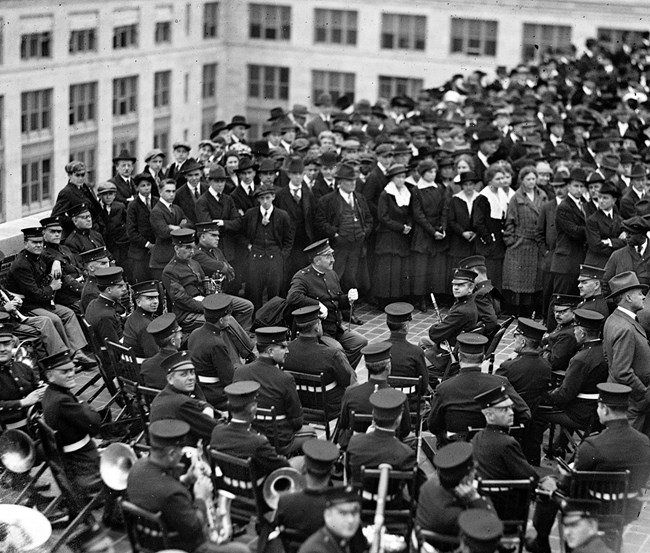

Library of Congress (LC-DIG-hec-09764)

77-year old DC native John Phillip Sousa attended the November 11, 1931 dedication ceremony, leading the US Marine Band in a 20-minute performance. His successful career was credited to the soaring patriotism of the era. Massive immigration to the US also created a deep need for national identity which Sousa’s marches delivered. Newfound leisure time allowed the people of the American industrial age to sit on the grass and listen to brass bands. The appeal was infectious. But it didn’t last. After World War II, technology, in the form of electrical amplification, and taste, shifting to Jazz and other styles, made bandstands obsolete. Over time, concerts at the DC War Memorial become rarer and rarer.

Flick'r/piet theisohn