Last updated: November 20, 2019

Article

Bat Population Monitoring at Booker T. Washington National Monument.

NPS photo

Why is the park interested in bats?

Bats are an important part of ecosystems and food webs. Though some species of bats feed on fruit, seeds, or pollen, the species that live in Virginia are insectivores. They consume huge numbers of insects every night, filling a unique ecosystem role as nocturnal insect predators. Unfortunately, a new disease called white-nose syndrome is affecting bats across the United States. To better protect bats, biologists are studying how local bat populations are changing.

Research Highlights

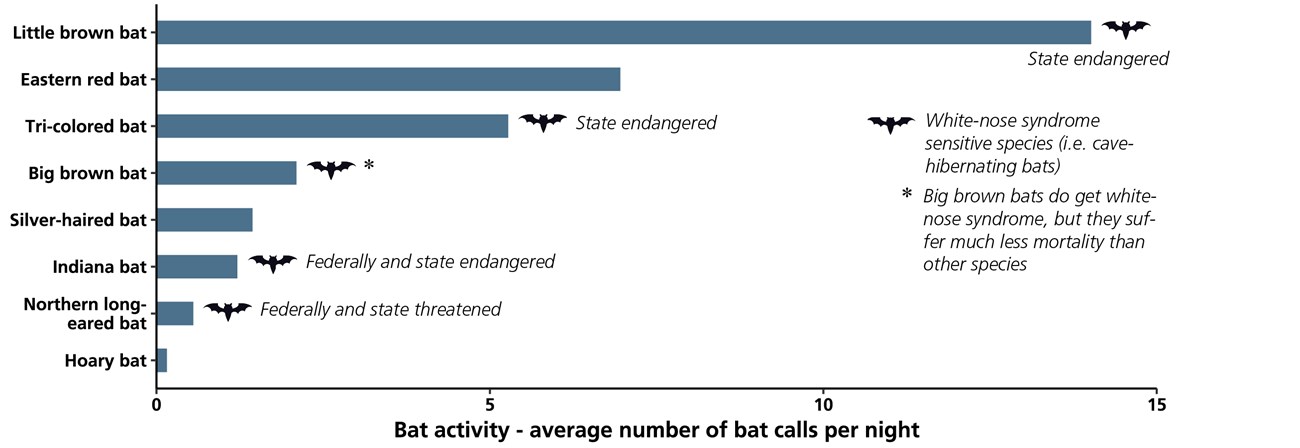

- Recent monitoring detected eight species of bats in the park, including two federally threatened or endangered species.

- White-nose syndrome has negatively impacted several species of bats.

- Importantly, the most common bat detected in the park was the little brown bat—a state endangered species.

How do biologists study bats? What have they learned about bats in the park?

Biologists have creative ways of studying these unique animals. Bats use echolocation to navigate and catch insect prey during the dark of night. People can’t hear these bat calls, so biologists use special microphones, called acoustic detectors, to record the sounds. By analyzing the bat calls, biologists can identify which specific bat species are present in an area during certain times of the year.

From 2016-2017, scientists used acoustic detectors to document eight species of bats in the park. The most commonly detected bat was the state endangered little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus). This is surprising as little brown bats have suffered tremendous recent declines as a result of white-nose syndrome.

Given the high levels of little brown bat activity, it’s possible that they are roosting or breeding in the park. Identifying these locations is important. Therefore, researchers are also capturing bats and using tiny radio-tracking devices to follow bats to important habitats. Park managers can then better protect these areas. For example, some bats return to the same breeding locations every year, including specific hollow trees or snags. Limiting disturbance to these areas can help bats.

What about other rare bat species?

During the summer, there are four rare bat species that can be found in the park. In addition to the little brown bat, the tri-colored bat (Perimyotis subflavus), the Indiana bat (Myotis sodalis), and the northern long-eared bat (Myotis septentrionalis) are also present. The latter two are protected by the Endangered Species Act and were rarely recorded by the acoustic detectors. This indicates that they are not common. All of these rare species are very sensitive to white-nose syndrome.

These rare bats spend their summer days roosting in tree cavities and snags, under tree bark, or in buildings. At night, they emerge to feed across the park’s landscape. During the fall, these species of bats usually travel to caves or mines, where they hibernate for the winter. In these caves and mines, they can contract white-nose syndrome and die.

NPS photo / Erickson Smith

What is the park doing to protect bats?

The data being collected on bats will help park managers conserve bats and their habitat. Protecting hollow trees and snags or buildings where bats raise their young and preserving mature hardwood forests will help reduce the impacts of the disease. White-nose syndrome remains an extraordinarily dangerous threat to bat populations—sadly, some species may ultimately disappear from the region.

Want to learn more?

For more information:

Contact Timbo Sims, Chief of Interpretation and Resource Management

Download a printable pdf of this article.