Bat Inventory at Rock Creek Park, BioBlitz 2016

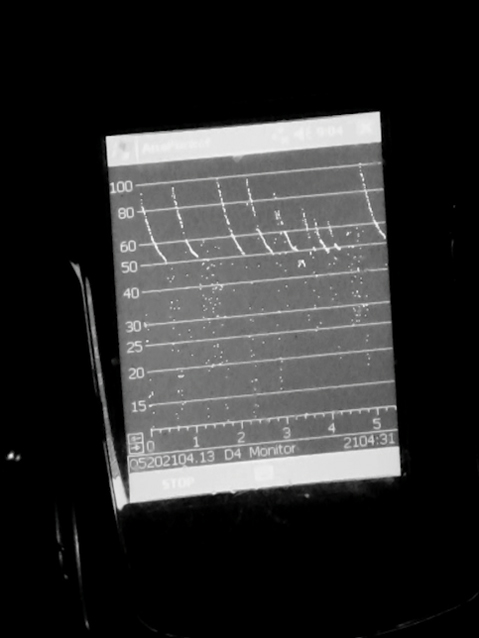

Eerie chirps erupted from an acoustic detector placed near the creek bank at Rock Creek Park on a full moon night in spring. Bat songs! Visual frequencies of their echolocation calls, called spectrograms, danced across the monitors. The bat inventory at Rock Creek Park had begun, and the bats were flying near.

On May 20-21 in Washington D.C., the National Park Service and National Geographic celebrated the NPS Centennial with BioBlitz 2016 — a national, multi-park, citizen science inventory of species involving an estimated 80,000 public participants. For two days the National Mall and D.C. area parks were buzzing with people of all backgrounds and ages keen to discover and document everything from insects and birds to plants and trees. Unlike other inventories in D.C., Rock Creek Park conducted a bat inventory led by a team of scientists and trained bat surveyors. Mist nets made of nylon mesh stretched across the creek in four locations. Curious BioBlitz-ers had come to the park, eager for a close view of the small and furry animals.

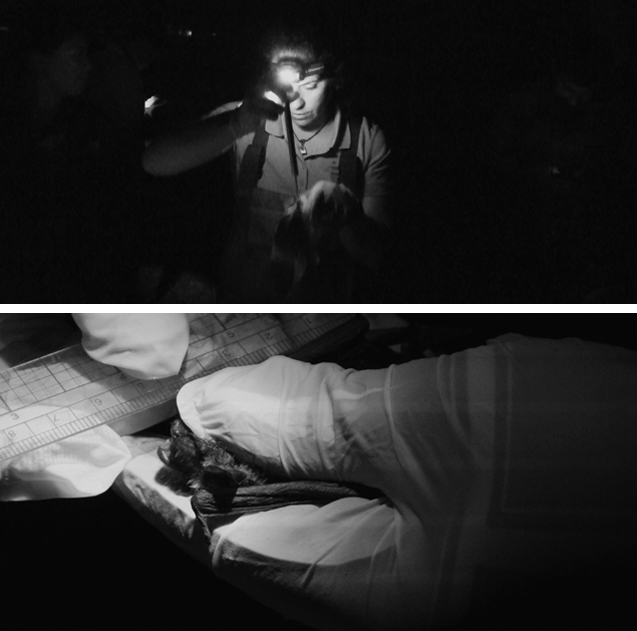

“We caught one!” called Scott McFarland, an NPS scientist on hand to help with the inventory, and the small crowd of people peered through the darkness to await the new arrival.

A creek-side picnic table served as a workstation for the biologists, whose headlamps threw spooky shadows but served to illuminate the scene.

“It looks like we have a big brown,” said Jessica Newbern, a visiting biologist from the Upper Delaware Scenic and Recreational River.

Julie West / NPS

The bat biologist team worked quickly to weigh and measure the bat—a male big brown bat, Eptesicus fuscus, which is native to North America and common in the D.C. region. This would be the first of five male big brown bats captured that night. Due to his smaller size, Newbern suggested he might have been a young male, born in 2015 from a small “bachelor colony” in the park, and foraging on his own for the season. Big brown bats typically eat 50-100% of their own body weight in insects each night, foraging multiple times in one evening. Bats can weigh between 14-21 grams (0.5 to 0.75 oz.), with females being larger than males. This first bachelor weighed a mere 14 grams but was just as feisty as any larger big brown bat.

With an open mouth, bobbing head, and a lot of noise, the tiny creature squirmed to free itself from the scientist’s firm but gentle grip. The bat handlers wore latex gloves over their thicker gloves, a necessary precaution to protect the bat from being exposed to pathogens, and the scientists from getting bitten.

“He’s so cute,” cooed several onlookers despite his fierce display.

And he was cute! But was he healthy?

White-nose Syndrome and other threats

Julie West / NPS

As an indicator species, a bat’s health relates to change happening in its natural environment. A fatal fungal disease called white-nose syndrome (WNS) is devastating certain bat populations in North America. The fungus infects the nose and skin of hibernating bats, destroying wing tissue and their immune systems. It also interrupts their sleep cycles, causing them to eat at odd hours, which increases their metabolic rate and reduces fat reserves. Was this big brown infected?

Newbern spread its wing to check for telltale signs of fungus. None! Fortunately for this bachelor and the other bats checked that night, the colony appeared to be doing well in spite of the threat of the disease. Routine inventories such as this help scientists spot early detection, which can aid in in their protection.

Bats have it rough, and disease is not the only thing hurting them. McFarland, volunteer bat surveyor and also an acoustic technician with the NPS Natural Sounds and Night Skies Division, is concerned about the impacts that noise and light pollution may have on their condition.

“As animals of the night, bats and their prey have adapted to night skies free from artificial light. In the last 150 years or so, artificial lighting has begun to affect this nocturnal environment,” McFarland said. “While the effects of light pollution are just beginning to be scientifically studied, some have already been found. For example, bats reduce their activity in areas where artificial lighting has been introduced.”

In addition, people often mistreat or kill bats because they don’t realize how important they are to the ecosystem. Big browns, like all bats in the D.C. area, are insectivores; they play a major role in controlling insect populations that, if unchecked, could result in the spread and increase of diseases, and loss of food crops. Bats are unsung heroes that play an important role in biodiversity, and provide free pest control.

Monitoring conditions

Julie West / NPS

The National Park Service is dedicated to the study and elimination of white-nose syndrome. In addition to capture inventories, parks are increasingly using acoustic surveys to monitor bat activity in parks. The data gives information about their distribution as well as their species, which parks can use to better target and manage populations.

Suddenly an acoustic detector burst with more activity, and the crowd drew close to watch the ultrasonic waveforms on the screen. Bats may be unsung, but who says they can’t sing?

“The spectrograms provide details that allow bat biologists, like me, to differentiate between certain bat species,” Newbern said. “Different bat species have call characteristics that are like a unique signature—calls vary in shape, frequency, duration, and intensity. The signals at Rock Creek looked hockey stick-shaped, with less slope between the high and low frequencies.”

McFarland and the biologists at Rock Creek Park safely released each bat after recording the data. It was past midnight by the time the inventory ended. That’s a lot of excitement for one night!

For the YouTube closed caption version: https://youtu.be/6lSamuWzDbA

For the YouTube audio described version:

https://youtu.be/UgHbuxFr5hU

Article and video by Julie West, communications specialist, Natural Sounds and Night Skies Division

Tags

- rock creek park

- white-nose syndrome

- bats

- bat

- eptesicus fuscus

- nps

- nps centennial

- national park service

- natural sounds and night skies

- natural sounds and night skies division

- night

- night skies

- natural sounds

- nocturnal

- washington d.c.

- district of columbia

- julie west

- jessica newbern

- lindsay rohrbaugh

- bat inventory

- inventory

- spectrogram

- spectrograms

- echolocation

- ultrasonic

- mammal

- fauna

- animal communication

- bat calls

- biodiversity

- big brown bat

- measurement

- measure

- inspection

- evaluate

- observation

- capture

- live capture

- dark

- park

- scott mcfarland

- bioblitz

- bioblitz2016

- citizen science

- nature

- nps careers

- park science

- science

- inventory and monitoring

Last updated: September 12, 2018