The Jay Treaty was enormously unpopular, particularly with Republicans. But from President Washington’s perspective, achieving peace and better commercial ties with an old nemesis was worth the risk of political disapproval.

“Damn John Jay! Damn everyone who won’t damn John Jay!! Damn everyone that won’t put lights in his windows and sit up all night damning John Jay!!!”

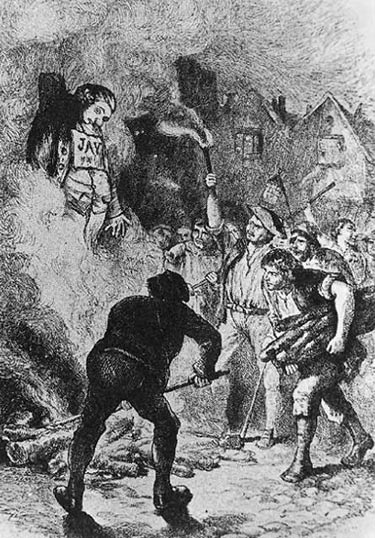

New York State Historical Association

The Senate approved the Jay Treaty in 1795, hoping to forestall war with Great Britain while America grew in power. But the treaty proved immediately unpopular with the Republicans—so much so that chief negotiator John Jay’s likeness was hanged in effigy by angry mobs all across America.

President George Washington believed he was acting in the nation’s best interests by negotiating the treaty rather than embarking on an openly hostile path with Britain. But some Americans viewed the terms of the treaty negatively. One critique of the Jay Treaty was its move away from America’s traditionally neutral stance toward the affairs of the Great Powers in Europe. Washington himself had issued a Neutrality Proclamation in 1793, urging Americans to avoid aligning with either rival in the struggle between France and Great Britain.

Washington’s subsequent decision to sign the Jay Treaty left Republicans fuming that he had effectively sided the nation with Britain, estranging America’s former ally France. Here Washington might have claimed pragmatism. Britain’s government was more stable economically and politically than the apparent chaos in Revolutionary France. And Washington correctly predicted that Britain’s naval supremacy would make it the more formidable adversary in a potential conflict. The President was thus willing to hazard political unpopularity to avoid a costly war.

Nor were the members of the Republican Party completely neutral themselves. Rather, they preferred close diplomatic ties with Revolutionary France rather than Britain. For one, they reasoned that the French people had been loyal friends during and since the American Revolution. The hated British, on the other hand, had tried to thwart America’s bid for independence and self-determination at every turn. And Republicans appreciated the anti-monarchical character and egalitarian spirit of the French Revolution. Washington’s Federalist Party tended to view such passionate attachment to France as naïve and overly emotional.

Republicans scorned Britain as an enemy of the common man. They imagined that reconciliation with the monarchical, aristocratic British would amount to a restoration of colonial dependency. That Federalists took the lead in thawing relations with Britain was particularly galling. Republicans decried their actions as evidence that they were crypto-Loyalists bent on betraying the ideals of the American Revolution.

Not surprisingly, the Republican Thomas Jefferson’s ascendency to the presidency in 1801 led to a change in diplomatic course. Republicans gradually moved away from Washington’s rapprochement with Britain. But a more antagonistic posture toward Britain resulted in a series of hostile exchanges—the Battle of Tippecanoe, the Chesapeake Incident, economic competition, and debates over the British seizure of American sailors on the Atlantic—that ultimately pushed both sides closer to war.

Last updated: May 24, 2016