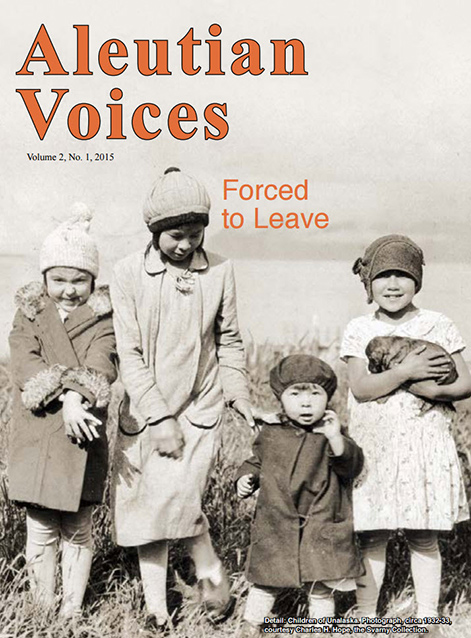

The [Unangax] were...the first and only people in Alaska to be assaulted by our own government and an enemy foreign power in WWII simultaneously.

Philemon Michael Tutiakoff, Chairman of the Board Aleutian/Pribilof Islands Association, Inc. 1981

Photo by Charles H. Hope, courtesy Sam and Gert Svarny

The Removal of the Unangax of Unalaska

“We [Unalaska Unangax] were cut off from the rest of our home island by a barb wire fence erected by the United States military. We had to conform to curfews, blackouts, respond to alerts and establish foxholes near every home. Our health facilities were inadequate… We were cut off from [our] food supply and had to make do with what we could buy from the stores. Our first taste of inflation came. Our church…was strafed. It was only after a very long lengthy struggle with the military that the leaders of Unalaska were able to have holes dug to store furnishings of the church.”

—Philemon Michael Tutiakoff

“[The Unangax] are a class of people that do little or no thinking for themselves…”

—Hugh J. Wade, Social Security Administration

“All the Natives out there need is a [telegraph] wire placing the teacher in charge of the evacuation and for them to get aboard ship. Those groups will do anything we ask them within reason.”

—Donald W. Hagerty, Interior Department employee and former Alaska Indian Service field agent

“It was humiliating for independent Aleuts to be treated like children. The evacuation made Aleut people feel as though they had no rights whatsoever. I noticed that we were referred to as ‘these people’ whenever there was a discussion about the evacuees. Well, ‘these people’ are now in control of their own destinies, as much as any American citizen is, and will continue to do a good job preserving their culture and traditions.”

—Alice Snigaroff Petrivelli

Image courtesy Archgraphics.

Prelude

Let us say it is a cloudless summer’s day. The waters of Iliuliuk Bay are blue-green and glassy, untroubled by even a breath of wind. This day, the light falls fully on the crescent-shaped beach that fronts the long, low stretch of the City of Unalaska. The wood frame houses and shops are painted blue, yellow, and red—the Russian Orthodox Church, rising above all, outlined against a backdrop of green folded mountains rendered in dark shadow and brilliant sunlight. The first people of the Aleutians, the Unangax, called this place Iluulux—”going in a half circle.”

To the Unangax, the natural world was sacrosanct. They knew and had given names to every feature on Unalaska Island, “…every little cape or small point of land... brooklet, rill and rock.” For the Unangax there was no separation between self and place; they were one with the encircling sea, the land and air.

Photograph courtesy Archgraphics.

Unalaska

“People of the [Aleutian] islands were not desolate and lonely. In their souls was a deep contentment that comes only to those who live close to the things they love.”

—William P. Zaharoff, Unangax chief, Unalaska

In 1942, the village of Unalaska numbers 289 people—151 Caucasians; 138 Unangax— the latter occupying 38 houses, some standing side by side with whites’ homes and businesses. To prevent a forced takeover by the U.S. military, residents apply for incorportation, and Unangax chief William P. Zaharoff is the first of 101 persons, white and Unangax, to sign the petition. March 3, 1942, Unalaska becomes a first-class city.

Photograph courtesy Museum of the Aleutians.

"Imported Workers"

“[Seventeen] of the native men are employed [by defense contractor

Seims Drake] but it will no doubt be temporary because of their nature.”

—Unalaska school principal Homer I. Stockdale

Early September 1940, an advance party of 59 white civilian construction workers arrives at Unalaska Village. They bang together a bunkhouse for themselves, then begin raising the frontier military base on neighboring Amaknak Island. In six months, they reach 430 in number. Many are from distant places in the “Lower Fortyeight,” their homesickness blinding them to the rough beauty of the place. For every laborer who arrives on the islands, another flees south.

These men did not come north for adventure, nor out of a sense of duty to country. It is a handsome paycheck—$175 a week—that brought them this great distance. But good money alone is not enough to sustain them. They are disgruntled over high living costs; over foul weather and dangerous working conditions. Medical care is poor and promises of overtime pay and recreation proffered by recruiters in Seattle, unfullfilled. The mood of the imported workers is “surly”—one not shared by Alaskan laborers on site who are accustomed to working under such conditions.

And the Unangax...

However well qualified, few are hired for defense work, Seims-Drake preferring to recruit whites from the states.

Many imported workers crack under the strain of working in the harsh Aleutian environment. Others are laid off due to labor disputes. Without employment, without means to buy their way back home, they wander Unalaska’s streets. Some turn to thievery, some to alcohol. Some beg. Rascism sits easily with many of these broken men, and the Unangax are openly abused by the outsiders, cursed and called “blacks.”

Photograph courtesy Archgraphics.

A City Under Seige

December 7, 1941, Japan attacks Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Fearing imminent Japanese invasion of Alaska, the United States intensifies fortification of the frontier bases at Dutch Harbor, Amaknak Island. Soon the military exhausts Amaknak’s useable land and turns to nearby Unalaska Island for further expansion. Brigadier General Edgar Colladay, Commanding Officer of Fort Mears, sees the flats of the City of Unalaska as a prime location.

As if laying siege, Colladay garrisons Army troops on the City of Unalaska’s perimeter. He places machine guns and antiaircraft positions inside town and requisitions city buildings for hospital use. But Colladay does not want Unalaska piecemeal; he needs the city whole.

“[The City of Unalaska] consists of a collection…of dilapidated buildings occupied by people of a nationality other than white… I would like to clean out… the entire town... The speed at which this can be accomplished, of course, will depend a lot on the ability of the Navy to help us. [Since] they are particularly anxious for housing for their construction battalions, I think we will have little difficulty along that line.”

—Brigadier General Edgar B. Colladay, Commanding Officer, Fort Mears

The white citizens of Unalaska are quick to profit from the massed presence of outsiders—civilian and military. A large general store is built, a movie house, curio shops, and cafes. Local whites let rooms; they sell supplies; sell Native handicrafts and picture postcards of the “Greek” church and local “Indians.” But the true money lies in hard liquor and beer. Soldiers, sailors, and construction workers stand hours in line suffering biting, wind-blown rain for their turn in one of Unalaska’s saloons. Inside, the crush of bodies is so great it is claimed a man cannot fall drunk to the floor even if his legs fail him. Not since the days of the Gold Rush has the town so prospered.

“...money flowed and liquor overflowed…[and] new saloons open almost every night, the red light districts spread and flourish while men and women search desperately for time-killers.”

—Dr. Ruth Gruber, personal field representative of Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes

“Soldiers from the post and sailors from the Navy ships in the harbor wandered about the crooked lanes and along the main street [of Unalaska]. They were looking for liquor and women. There was much of one and little of the other... Prices were high for both.”

—Gore Vidal, Williwaw

“Blackie’s” Unalaska Bar offers solace in a shot glass—fifty cents a whiskey. For another fifty cents, passage by rowboat can be bought from Unalaska across Iliuliuk Harbor to Expedition Island. Here there is a small dock, a melancholy stand of spruce trees, and a two-story frame house—home to five working women and a madam. Business is brisk at “Pleasure Island,” and word of profits finds it way south. In Seattle, like-minded entrepreneurs attempt to book travel to the territory. The Alaska Steamship Company denies them passage. It is of no consequence. The brothel on Expedition Island is short-lived, the house shut down by the U.S. Navy and the women refused relocation to Unalaska Island by the deputy federal marshal. For those men who had taken the journey by rowboat, it had cost them fifty cents to reach Expedition Island, but two dollars to leave.

The Unangax profit little in the booming “defense town.” One-third the land within city limits is Native-owned, but whites have cornered much at cheap lease rates. These white middlemen turn around and lease again the same parcels at great gain.

Dr. Ruth Gruber, personal field representative to the Secretary of the Interior Ickes, reports that wartime Unalaska is in “upheavel.”

The city has psychologically “gone berserk,” Gruber writes.

Photograph courtesy the Svarny Collection.

Considered “exotic” by soldiers, young Unangax women can not walk safely the city streets of Unalaska at night for fear of attack. “Intermingling” is what the authorities call such interactions between Native women and white men. To curb such contact, the army raises a barbed wire fence round the City of Unalaska. But the fence stands not as safeguard for the Unangax, but as a means of isolating them. Brigadier General Colladay believes that the Unangax have a harmful effect upon his men.

The white principal of the Unalaska School, Homer Stockdale, concurs. He writes that the “unmoral nature [of the Unangax] makes them a menace to soldiers and imported workers...” The status of the Unangax is so grave, Stockdale continues, as to be “beyond the Federal law to express through the United States mails.” The Unangax find themselves undesirables in a place they have inhabited for millenium—held responsible for the social ills visited upon them from outside.

Dr. Ruth Gruber.

Aleutian Faces - Dr. Ruth Gruber

Born in Brooklyn, New York 1911, Ruth Gruber earned a Ph.D. from the University of Cologne, Germany at the age of twenty—the youngest person in the world at that time to receive such an advanced degree. In 1941 she was appointed Special Assistant by Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes—her assignment to access Alaska’s potential for soldiers to homestead at war’s end. While at Unalaska, Gruber witnessed firsthand the effects of militarization on the Unanga{ of Unalaska City. Believing a Japanese attack on the Aleutians imminent, Gruber sent a confidential cable to Secretary Ickes urging the Unangax be removed from the islands for their own safety. Years later she would write of her visit to the displaced:

“I learned what it meant to be a refugee.”

“In Funter Bay [Unanga{ Internment Camp, SE Alaska], I had my first experience with refugees. I learned what it means to be a refugee: homeless... disoriented, and on the run. He knows trauma and loss. His memory of home turns even the simpest cottage in which he once lived into a villa.

“The Aleuts were told by the army that at the end of the war, they would be taken home. But how could they believe it?

“I felt quilty. I was responsible* for turning the islanders into refugees. There were a few people who did call the evacuation ‘Gruber’s Folly.’ I had no idea that the evacution and life in the camp would be so painful for them, depressing them...

“The experience, difficult as it was for me to see their hardships, helped prepare me for a life dedicated to rescue and survival.”

—Dr. Ruth Gruber Inside of Time

Photographs courtesy Museum of the Aleutians.

The Attack

“...women and children [at Unalaska]...were machine-gunned... [Japanese] planes flew over them scattering bullets but by some miracle they missed... Contrary to reports I do not think the Natives were more frightened than the whites, nor were they shaking like leaves. They did as they were told calmly and quietly…”

—Martha Tutiakoff, Indian Affairs Hospital Ward Attendant

June 3, 1942, almost six months to the day after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese carrier-borne aircraft strike the military installations on Amaknak Island. June 4, Japanese fighter and bomber planes return. This time, several aircraft divert to Unalaska City to silence antiaircraft fire. The Church of the Holy Ascension is strafed, and a bomb blast shatters one end of the Indian Affairs Hospital. No one is harmed. On 7 June, Japanese landing forces occupy the western Aleutian islands of Kiska and Attu. Forty-two Attuans are taken prisoner, and it appears certain a Japanese invasion of Alaska will follow.

“We try to teach [the Unanga{ children] safety, but of course they have very primitive tendencies and forget the teachings when convenient to do otherwise.”

—Unalaska school principal Homer I. Stockdale

In Unalaska City, the Unanga{ bury religious articles from their church for safekeeping. They dig foxholes close to their homes, carry gas masks, and black out their windows at night. Large military trucks rumble down city streets that not long ago saw only pedestrians or the rare automobile. Accustomed to playing free, Unanga{ children must be “taught” how not to be run down in traffic. Hemmed in by barbed wire, separated from their fishing grounds, the Unanga{ turn to city stores for footstuffs. They are captive customers, and prices soar. With the destruction of the Indian Affairs Hospital, medical care falters. Unalaska’s chief nurse, Margaret Quinn, recommends “immediate evacuation.”

“[The Unangax] seemed to have no conception of cleanliness or orderliness and the majority of their homes have little value as buildings and contained little furniture. Any type of shelter seemed to suffice. ”

—Brigadier General Edgar B. Colladay, Commanding Officer, Fort Mears

Postcard courtesy Archgraphics.

To address the wartime state of Unalaska, a “defense council” is formed of whites only. The Unangax number nearly one-half the population of Unalaska City, but are governed by whites and policed by whites. Granted full citizenship in 1867 at the purchase of Alaska from Russia, they have stood as Americans for 75 years, but are deemed “Indians” by the federal government—“wards” of the Department of Interior with no more say in the conduct of their lives than children. Army Brigadier General Colladay argues that he “would have to take care of them while they are in our midst, to the detriment” of soldiers. Hugh J. Wade of the Social Security Administration writes that the Unangax “are creating a major social problem,” and the sooner they are removed the better. It appears that to all in power—even those who believe they have the welfare of the Unangax at heart—it would be best if the Natives of Unalaska were shipped elsewhere.

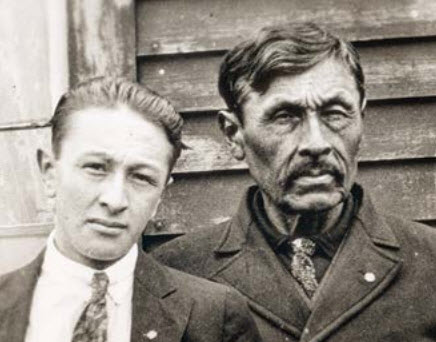

Photograph courtesy University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Aleutain Faces - Alexei and John Yatchmeneff

Two generations of Unalaskan Unangax: right, Alexei Meronovich Yatchmeneff; left: his son John. For 45 years, Alexei stood as chief among chiefs in the Eastern Aleutians. Born June 1866, he witnessed Unalaska’s transition from Russian colony to U.S. territory. Chief Yatchmeneff died in 1937 and did not see the swift and terrible changes world war would bring to the Aleutians.

“...half wards and half free men.”

John Yatchmeneff was the only Unangax elected to Unalaska’s wartime City Council. On 16 May 1941, the younger Yatchmeneff wrote to President Franklin D. Roosevelt that the Unangax were denied the same constitutional guarantees as whites—that they were held in unenviable status as “half wards and half free men.” It was unprecedented that a Native put such words to paper. Two anthropologists were sent to Unalaska as undercover investigators by the Alaska Indian Service to investigate the Yatchmeneff letter. Favored by U.S. Commissioner Jack Martin, John stayed on in Unalaska during internment. He drowned there shortly after the evacuation.

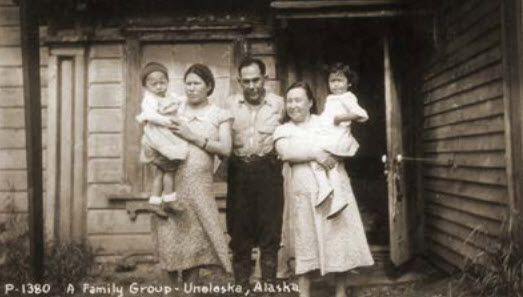

Courtesy Charles H. Hope, the Svarny Collection.

Removal

July 18, 1942, the Unangax are told they have twenty-four hours to leave their homes. They may take only what they can carry—a suitcase, a trunk. There is no time to shutter windows and secure doors, to turn off water or cover stovepipes against the blowing rain. In their baggage they are allowed only clothing...no photograph albums, no keepsakes, no religious article—icon or holy lamp—no physical sign of the life they leave behind. Military police will search through their things before the bags are closed and locked. Dogs and cats must be left. Young children will carry what remains of their world in pillow sacks.

July 19, 1942, Hobart W. Copeland, Army captain in charge of removal of the Unangax, reports that several Natives refuse to leave the island. Copeland asks “for authority to compel them.” Among the Unangax to be displaced are elders, pregnant women, and four infants one year old or less. No one is told where they will be taken, nor for how long. Commander William N. Updegraff, Naval Air Station, Dutch Harbor, orders Copeland that all Natives are to go, all persons with “as much as one-eighth native blood” in their veins. Since the mid-1700s, Caucasians and Natives in Unalaska have mixed their blood, but on 19 July 1942, a search is begun to determine who is “native” and who is not. A one-eighth “blood quantum test” will decide.

“The most galling and demeaning feature that many of us recall explicitly is that those in charge regarded us [Unangax] as incapable…of any form of decision-making. At no time throughout this entire process were we given the right to make choices of any kind.”

—Philemon Michael Tutiakoff

July 22, 1942, one hundred and thirty-seven Unangax are herded onto the steamer S.S. Alaska in Captains Bay. As they board ship, the purser impounds the hunting rifles and shotguns the Unangax men were ordered to bring. Some in command fear the Unangax have been so mistreated by the United States, they may take to arms for the Japanese. The S.S. Alaska departs late that afternoon, women and men separated into different compartments, the men in a common hold with only the blankets they have brought. The following morning, the Unanga{ wake to find the ship in dense fog. Standing at the railing, they can see nothing of what lies ahead. In Unalaska City, whites continue to go about their business. The military expands into the valleys and hills of Unalaska Island, unencumbered by the original inhabitants of the land.

“Aleuts would be safer placed upon other islands remote from the Base where they can live by hunting and fishing, and in canneries rather than be left here as a menace to military maneuvering and victims of starvation in case of a siege.”

—Unalaska school principal Homer I. Stockdale

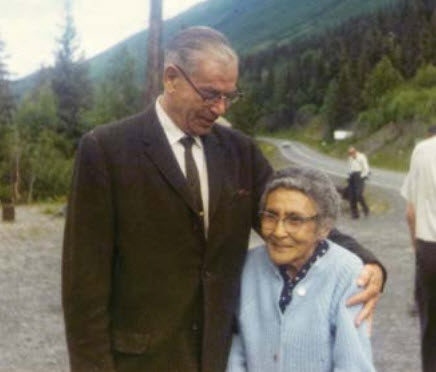

Edward Lewis Bartlett Papers, 1938-1970, UAF-1969-95-312.

Aleutian Faces - "Little Grandma"

“[Anfesia] was a very diminutive woman, a very tiny woman. But could be extremely fierce at times if she found something out that she was unhappy with. And she was often unhappy with the written accounts of Aleut history... When I knew her she was an older woman...in a sense the matriarch of the community [of Unalaska].”

—Ray Hudson

Born 1 October 1901 on Atka Island—her father from Atka, her mother an Attuan. Anfesia Shapsnikoff moved to Unalaska circa 1905. She was literate in three Unangan dialects and in both Russian and English. Small in stature, her appearance belied her vitality and strength.

The Twenty-first Legislature of the state of Alaska recognized Anfesia in 2000 as an “Aleut Tradition Bearer” who “...served as nurse, church reader, teacher and community leader nearly all her life...who contributed history and well being for all Alaskans.” A master basket weaver, she travelled the Aleutians teaching children the fine art of Attuan weaving. Anfesia passed away January 15, 1973 and rests in the Holy Ascension Cathedral Churchyard at Unalaska, close to the icons and religious articles she so loved and protected.

In 1942, in defiance of U.S. military order, Anfesia Shapsnikoff, together with the Church Committee, brought the icons of Unalaska’s Church of the Holy Ascension south to the internment camp at Burnett Inlet. There, the paintings were hung in a small church built by the Unangax men. When weather permitted, the Unangax aired the icons. They coated them with 3 in 1 machine oil— the only “preservative” that could be scavenged. But still the ever-present damp of the rain forest permeated the canvasses. The icons began to mold, then flake. Brittle oil paint, centuries old, cracked and curled and fell away. In desperation, the Unangax applied shellac to slow the icons’ decline, but the mix of oil and shellac darkened the once glowing paintings and they began to recede into the dusk.

“[The Unangax] first concern” was “for their churches…and the treasure of art objects” in them.

—Doris Ann Plummer, Wrangell insurance broker selling “war risk” policies for Unangax property left behind during relocation.

About Aleutain Voices

This project was funded by the National Park Service, Affiliated Areas Program in support of the Aleutian World War II National Historic Area, in cooperation with the Aleutian Pribilof Heritage Group.

For more copies of this publication or for more information about the Aleutian World War II National Historic Area contact:

Alaska Affilated Areas

240 West 5th Ave

Anchorage, Alaska 99501

(907) 644-3503

Ounalashka Corporation

P.O. Box 149

Unalaska, Alaska 99685

Visitor Information (907) 581-1276

Visitor Center (907) 581-9944

Tags

- aleutian islands world war ii national historic area

- world war ii

- alaska

- aleutian campaign

- japanese occupation

- internment

- world war ii alaska

- wwii

- relocation camps

- aleut relocation

- aleut evacuation

- aleut removal

- unangax evacuation

- unangax relocation

- unangax removal

- japanese invasion

- pribilof

- russian orthodox church

- history

- akwomen

- conflict

- war

- women

- alaska native

- indigenous people

Last updated: September 25, 2025