Born in the late 1800s, Abbie Joseph's life is emblematic of a subsistence lifestyle in Interior Alaska that has endured for thousands of years, and which continues today. Interviews with her in the 1980s give a personal and unique perspective on the traditional lifestyle of Alaska Natives in the Denali area.

There were a lot of chum salmon around Khutenal'eedenh [hidden place] ... We would go there and make summer dry fish. We’d also put away frozen fish after freeze up ... So that was a good area; it provided us a good living. Abbie Joseph

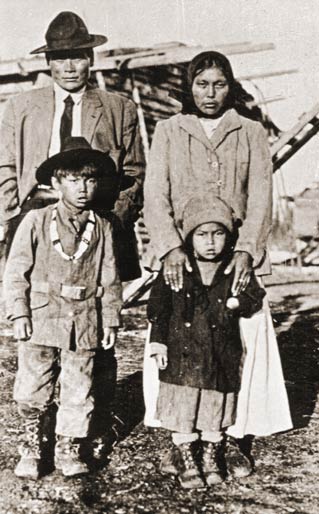

Stephen Foster Collection, 69-92-335, Archives University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Denali, a landscape widely regarded as untouched wilderness, has been home to people for thousands of years. Alaskan Natives moved seasonally to harvest the resources of the land needed for their food, shelter, clothing, and other material goods. This human presence is evident in both the hundreds of archaeological sites found in Denali’s wilderness areas and the enduring use of some areas of the park for subsistence activities. Continuity of this subsistence life is reflected in the early 20th century life and recollections of Abbie Joseph, a Koyukon-speaking Athabascan woman who lived in the Denali area.

Living in Denalee

“I lived with my parents at Denalee (Denali/Mt McKinley), at the foot of it. From our home on Birch Creek, we went up and moved around on the hills. Every summer we looked for caribou way up where the river comes out from the mountains. It is dangerous at the head of the river because of the ice. It looks like solid ground, but there are holes in the ice that are concealed by moss and lichen on top. The caribou would be found there.

Along the way to the mountains there is an overhanging ledge, like a porch on a house. Willows grow around it, so it is sheltered from the rain. There, we would always camp. We set up our tents. There was lots of room. We made a smokehouse too and dried caribou, sheep—everything we caught. We made dry meat, just like drying fish.”

-- Abbie Joseph

Charlene Craft LeFebre Collection, Tochak Historical Society, McGrath, Alaska.

A Subsistence Life

Abbie’s family lived a life of subsistence, travelling a well-known territory during the seasonal round—by foot, watercraft and dog team—from the mountains of Denali to the lowlands of Lake Minchumina. Large mammals, principally caribou, moose, and Dall sheep, were the primary source of food, clothing, and shelter. Fish, especially whitefish, was a critical resource, seasonally. Important secondary resources included berries, waterfowl and smaller mammals. Spruce, birch, alder and willow provided materials for tools, twine, traps, shelter, bowls, sleds, boats, and weirs.

Abbie lived within the Kantishna drainage of Denalee until widowed in 1920. After marrying Edgar Joseph, she lived at Fish Lake (off the lower Tanana River) for many years before moving to Tanana. Abbie had six children and she adopted two more in Tanana. She passed away in 1986.

Charlene Craft LeFebre Collection, Tochak Historical Society, McGrath, Alaska.

"All of us are like one ..."

“I have relatives all over—Toklat, Cos Jacket, Nenana and Telida. My poor (deceased) old uncle, Seseui, was my dad’s brother-in-law. Uncle Seseui really cared for us and talked lovingly like he was the one who raised us.

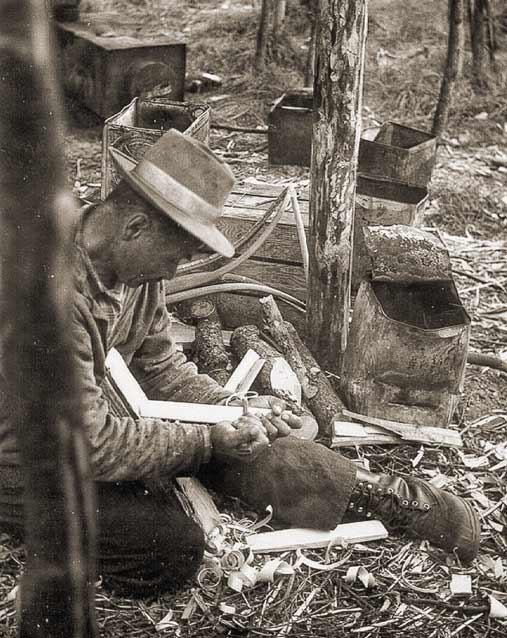

“When I was a child, Uncle Seseui would visit us every summer. He traveled up from Telida toward the mountain, following the hills to the head of Birch Creek. There he took down a beat-up birch bark canoe from where it hung and repaired it with spruce pitch. Then he put it in the water and traveled downstream. He brought us special things—bone marrow, caribou kidney, feet and good dried meat. He had a lot of things in a bundle that was lashed to the canoe. As he approached our camp, he would say, “Come, my children. Wait there.

“From the river bank we would call, ‘Mom, uncle is coming!’ So we stood there and then from under the bow he would pull out his bag. We always called him ‘really, really uncle.’ Although he wasn’t a blood relative, he was related to us because he was so caring.”

-- Abbie Joseph

Charlene Craft LeFebre Collection, Tochak Historical Society, McGrath, Alaska.

Sources

Interviews: Abbie Joseph, who spoke a variant of Koyukon Athabascan (Denaakk'e), was interviewed in the early 1980s by Dianne Gudgel-Holmes, ethno-historian and Eliza Jones, linguist, then with the Alaska Native Language Center. Abbie’s deafness made interviewing a challenge. Her stories are rich in details about her vast wilderness neighborhood and her subsistence life in the early 20th century.

Additional Information

Last updated: October 26, 2021