The Big Hole National Battlefield landscape is recognized both as a historic site and as a memorial to those who lost their lives in the battle. This period of significance begins in 1877, the year of the battle, and concludes with the 1883 placement of the soldiers' monument. The site continues to be characterized by the physical features and natural systems that influenced the battle, conveying a sense of the events and the landscape's role in history.

“Hear me, my chiefs, I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands I will fight no more forever.” Chief Joseph, October 5, 1877

NPS

Big Hole National Battlefield was the site of a battle between the U.S. Army with Montana citizen volunteers and the Nez Perce people on August 9-10, 1877. The battle was part of a five month conflict in which the army, intent on moving the Nez Perce to the Lapwai Reservation in Idaho, pursued roughly 750 men, women, and children across 1,170 miles from the Wallowa Valley in Oregon to the Bear Paw Mountains, just 40 miles from the Canadian border in northern Montana.

Along the way, the two sides met in a series of confrontations during which scores of people were killed, including soldiers, citizen volunteers, and Nez Perce men, women, and children. Exhausted, cold, and hungry, the remaining Nez Perce surrendered at the Battle of Bear Paw on October 4, 1877.

The Battle of the Big Hole was a critical event in the war. After some success against the army in earlier skirmishes in Oregon and Idaho, the Nez Perce believed that they had eluded their pursuers and were relatively secure. They had planned to either solicit help from the Crow bands of Montana or to continue to Canada, where they might be safe from the U.S. forces.

Believing the army was well behind them, they no longer felt the urgency of the pursuit, and they planned to take some time for needed rest and to gather necessary supplies. At Big Hole, however, they were overtaken by Colonel John Gibbon and the 7th U.S. Infantry, who surprised the Nez Perce in a pre-dawn attack on the morning of August 9.

The Nez Perce would eventually gain the upper hand in the battle, dealing a decisive blow against the infantry, but it would come at a dire cost. The actual count of Nez Perce wounded and dead is unknown, but it is believed that between 80 and 90 individuals were killed, with at least two thirds of those women and children. On the side of the military, 3 officers, 21 enlisted men, and 5 civilians were killed.

The battle is generally considered a tactical victory for the Nez Perce, who held the soldiers at siege long enough to bury their dead, gather their camp, and escape with the majority of their horses. However, the great losses they suffered were devastating and contributed to their ultimate defeat two months later.

Big Hole National Battlefield is extends across a western tributary valley of the Big Hole basin in southwestern Montana. Since the battle, the Big Hole Battlefield has been recognized and honored both as a historic site and as a memorial for those who lost their lives in the battle. The period of significance includes the battle and its immediate aftermath, beginning in 1877 and concluding with the placement of the soldiers’ monument in 1883.

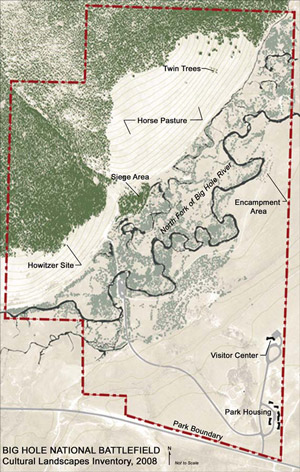

Today, the elements of the landscape that are essential in conveying the site’s significance are remarkably intact, combining to create a scene very similar to the one that existed on the morning of August 9, 1877. Of particular contribution are the vegetation patterns, including the extent and character of the forest, the open horse pasture on the hillside, the dense willow thickets, and the open meadows; the meandering river, with its associated bogs, sloughs, and ponds; the topography of the mountain slope, low river bottom, the prairie bench, and the point of timber where the soldiers were besieged; and the unobstructed views. Comparison of the current landscape with first hand descriptions of the battlefield and with drawings that were made by battle participants suggests a high degree of similarity.

text

Quick Facts

- Cultural Landscape Type: Historic Site

- National Register Significance Level: National

- National Register Significance Criteria: A

- Period of Significance:1877-1883

Landscape Links

Last updated: January 21, 2026