Bathhouse Row in Hot Springs, Arkansas is the largest remaining collection of twentieth-century bathhouses in the United States. The row of bathhouses draws upon many architectural influences, while still displaying cohesion. The landscape provides evidence of developments in design, recreation, conservation, and health and social history, suggesting a period when bathing was viewed as an elegant leisure activity with healing potential.

NPS/Hot Springs National Park

NPS / Hot Springs National Park Library and Archives

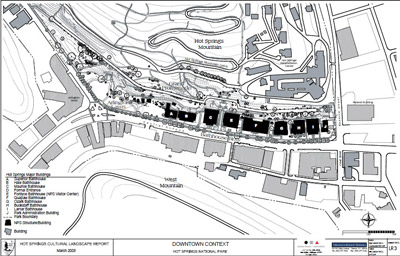

Hot Springs National Park is located in west-central Arkansas at the southeastern edge of the Ouachita Mountains, approximately 50 miles southwest of Little Rock. A large portion of the park is mostly-forested area where the mountains are interlaced with the city of Hot Springs. The park's resources are also central to Hot Springs; Bathhouse Row, located along Central Avenue in the downtown core of the city, holds most of the park’s architectural resources.

The Bathhouse Row cultural landscape is located along the foot of Hot Springs Mountain. It is identified it as one of six landscape character areas within the 18-acre Reservation Front. The cultural and natural features of the surrounding areas are evidence of the historic recreational and spa experience that have brought visitors to Hot Springs since the 1830s. Bathhouse Row is historically designated as an “architectural park” in which the buildings and landscape were designed to be a cohesive unit.

Bathhouse Row is significant as the largest remaining collection of early twentieth-century bathhouses in the United States, representing the peak in the nation’s spa movement. Periods of significance are identified as 1885-1897, 1912-1923, and 1930-1959. These correspond to developments in architecture, landscape design, recreation, conservation, heath, and social history. The thermal waters were used as a therapeutic aid, comparable to European spas of the time. The landscape also reflects national attitudes towards health, leisure, recreation, and conservation. Additionally, the site is important within the context of the National Park System. During its development, the primary resource for which the park was formed was used rather than being conserved in a natural state.

NPS

It is likely that Native Americans used the thermal springs and associated landscape long before the bathhouse period. The first Euro-American settlement and construction in the area occurred in 1807, and by the 1840s a row of wooden bathhouses had been added. Over time, construction methods improved and safer, more secure structures replaced original ones.

The currently-existing bathhouses date to a time of improvements during the years 1912 to 1923, when there was new focus on sanitation and equipment. Different building styles and changes to the bathhouses over time reflect transformations in the bathing industry, advances in technology, and evolving social mores.

In the 1890s the Department of the Interior attempted to enhance the landscape through formal design and creation of a more tasteful natural setting in the surrounding area. Many significant features of the landscape were added during this period, characteristic of informal Victorian landscape design. When the National Park Service was created in 1916, the agency began managing the Hot Springs Reservation. It gained the National Park designation in 1921.

NPS

During the subsequent era, emphasis began to shift from formal design to conservation. Alterations include the hillside pathway known as the Grand Promenade (built 1930s-1958), new sewer and lighting systems, streetcar lines, and plans for removal of some buildings to give Hot Springs the character of a “real national park.” Although the bathhouses continued to operate after this period, the trend and use declined after reaching a peak around 1947.

The Bathhouse Row buildings exhibit cohesion in architecture, scale, orientation, and landscaping, despite being altered over a span of years. Within this unity, they possess diversity of materials and styles, drawing upon many architectural movements. The landscape continues to convey trends in architecture and landscape design; moreover, it suggests the character of a period during which bathing was viewed as an elegant leisure activity and as an option for healing. Today, the cultural role of bathing rituals has been replaced by other activities, and only Buckstaff and Quapaw provide baths.

Quick Facts

- Cultural Landscape Type: Designed, Historic Site

- National Register Significance Level: National

- National Register Significance Criteria: A, C

- Periods of Significance: 1885-1897, 1912-1923, 1930-1959

- National Historic Landmark

Landscape Links

Last updated: March 23, 2021