Monroe Elementary School is located in a neighborhood of Topeka, Kansas that is now a mix of residential, industrial, small business, and vacant properties. The school and neighborhood were important sites during the Brown v. Board of Education case of 1954, in which the U.S. Supreme Court concluded that "separate educational facilities are inherently unequal." The landscape provides evidence of education during segregation and the challenges and changes that followed.

"We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal." Earl Warren, Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court (May 17, 1954)

NPS, Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site

Kansas State Historical Society / NPS

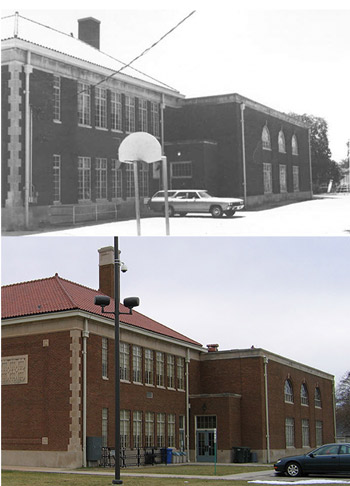

The historic landscape and structures of Monroe Elementary School in Topeka, Kansas are primary physical resources associated with the landmark Oliver Brown et al. v. Board of Education of Topeka case and the U.S. Supreme Court decision handed down on May 17, 1954. Since being declared a National Historic Site in December 1992, the school building and surrounding property have been under the management of the National Park Service. Monroe School was opened to the public in 2004 and currently features interpretive programs to inform and educate visitors on local and national issues relating to the Brown v. Board decision.

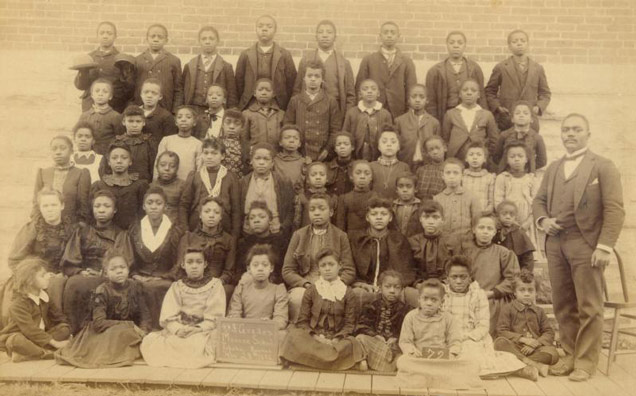

The Monroe Elementary School is a significant landscape because of its association with the case of Brown v. Board of Education (1954), in which the U.S. Supreme Court concluded that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” This denied the legal basis for segregation in schoolrooms, initiating a revolution in the expression of equality and the legal status of black Americans that still continues. The Sumner Elementary School of Topeka refused to enroll Linda Brown on the basis of race, leading to the case that would give name to the court’s decision. Before the Supreme Court verdict, Linda Brown attended the segregated Monroe Elementary School. The location of both schools and the quality of education they provided to the plaintiffs were material to the finding of the Supreme Court in the Brown decision.

NPS

The Monroe School is located in an economically depressed neighborhood of Topeka that is comprised of residential, light industrial, small business, and vacant properties. An important site in the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case, it is historically related to other cultural sites in the city. The landscape illustrates the vernacular character of Topeka elementary schools and the features reflect the historic land use, supporting and expressing the significance of the site’s associations.

There is not a great deal of written, graphic, or photographic documentation of the Monroe School landscape during the 1950-1954 period; however, the ones that do exist, in combination with oral testimony, provide a fairly coherent image of the historic landscape. This inventory depicts details and recollections of the landscape from before and after the time of integration. Monroe closed in 1975 due to substandard facilities and low enrollment. It continued to be used for storage, utilities, and by the Church of the Nazarene until it was transferred to the National Park Service.

NPS / Mannikko

Before opening the school to the public, the NPS initiated research efforts aimed at achieving an understanding of segregation and the civil rights movement in the context of Topeka. The current landscape consists of a fenced lot with the Monroe School building at the center and concrete paving on the front (east) side, an asphalt-paved lot on the north side, and grass and gravel on the south and west. The west side is bounded by a narrow alley and rear walls of residential properties that front on South Quincy Street. A few trees line Monroe Street along the front of the school. There is no extant playground equipment. The adjacent grassy lot, on the east side of Monroe Street, contains only a chain-link fence baseball backstop at the northwest corner. This lot is bounded by a railroad track on the east side. It was historically associated with and used by the school, and is part of this landscape. An original steel flagpole also remains in the school lot. Overall, the site retains a moderate amount of integrity, and many of the remaining features continue to help illustrate the school's associations with the time period and the landmark court decision.

Quick Facts

- Cultural Landscape Type: Historic Vernacular

- National Register Significance Level: National

- National Register Significance Criteria: A

- Period of Significance: 1951-1954

Landscape Links

Last updated: January 21, 2026