Last updated: October 7, 2024

Article

Working Women at Vancouver's Kaiser Shipyards

FOVA 219207

NPS Photo, FOVA 281696

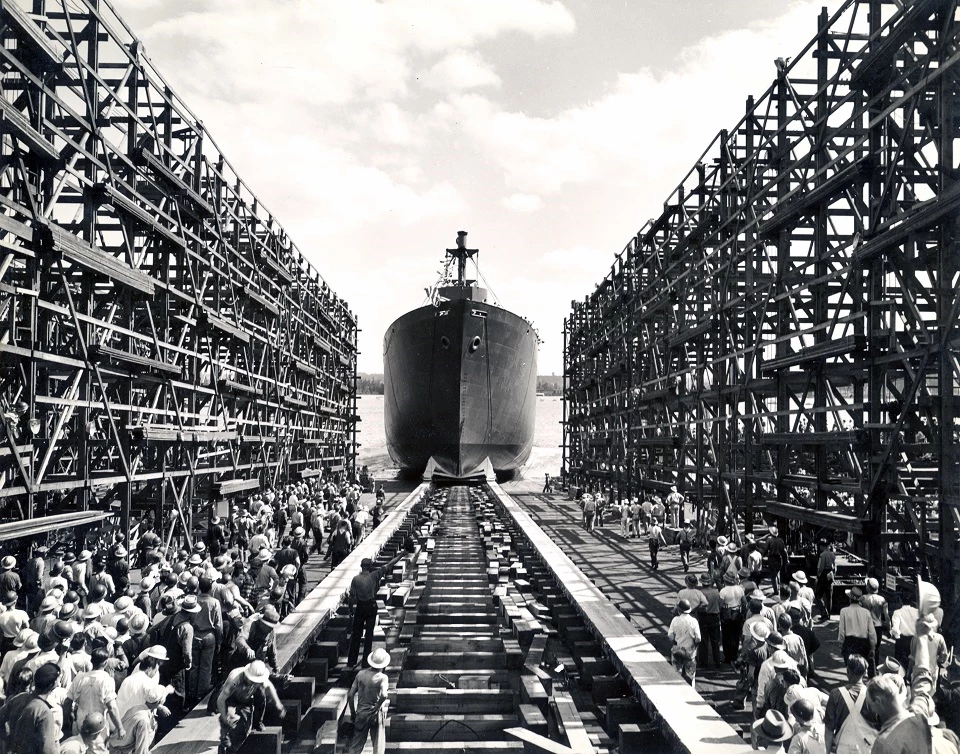

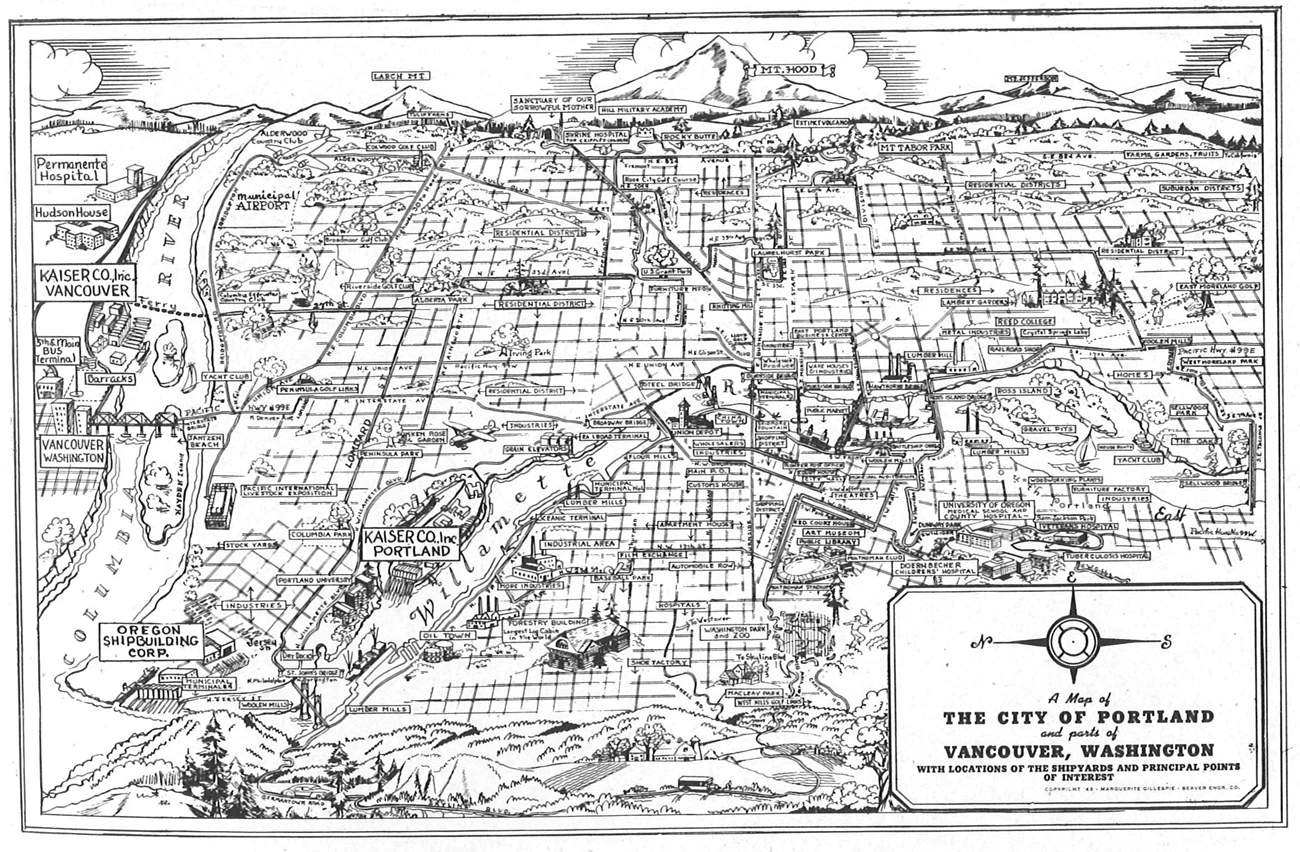

During World War II, Vancouver and Portland were the site of shipbuilding yards. In January 1942, one month after the United States declared war against the Axis powers, industrialist Henry J. Kaiser signed shipbuilding contracts with the United States Maritime Commission. These contracts allowed Kaiser to build seven shipyards throughout the Western United States where laborers would construct ships for battle and transport in the war's Pacific Theater.

Of these seven shipyards, one was located on the Columbia River at Vancouver, Washington. Two more shipyards were located nearby along the Willamette River in Oregon. These shipyards were rapidly constructed and needed thousands of workers to operate. Recruiters traveled throughout Midwestern and Eastern cities to mobilize a shipbuilding workforce. The shipyards needed welders, riveters, electricians, administrative staff, and more. Recruiters emphasized that no prior education or experience was needed. Recruitment for the shipyards proved to be quite successful, as thousands of people – men and women who arrived alone or with their families – uprooted their lives to work at the Kaiser Shipyards.

NPS Photo, FOVA 281696

The beginning of 1943 was the height of shipyard employment for the Vancouver Kaiser Shipyard, with well over 30,000 workers hired in total. These high rates of employment and production caused record breaking shipbuilding over the course of the war. By the war's end, the Vancouver Shipyard had launched over 130 ships. In total, the three Kaiser Shipyards in Vancouver and Portland produced over 700 ships: 30% of all ship production under the US Maritime Commission during World War II.

NPS Photo, FOVA 281696

Women at the Kaiser Shipyards

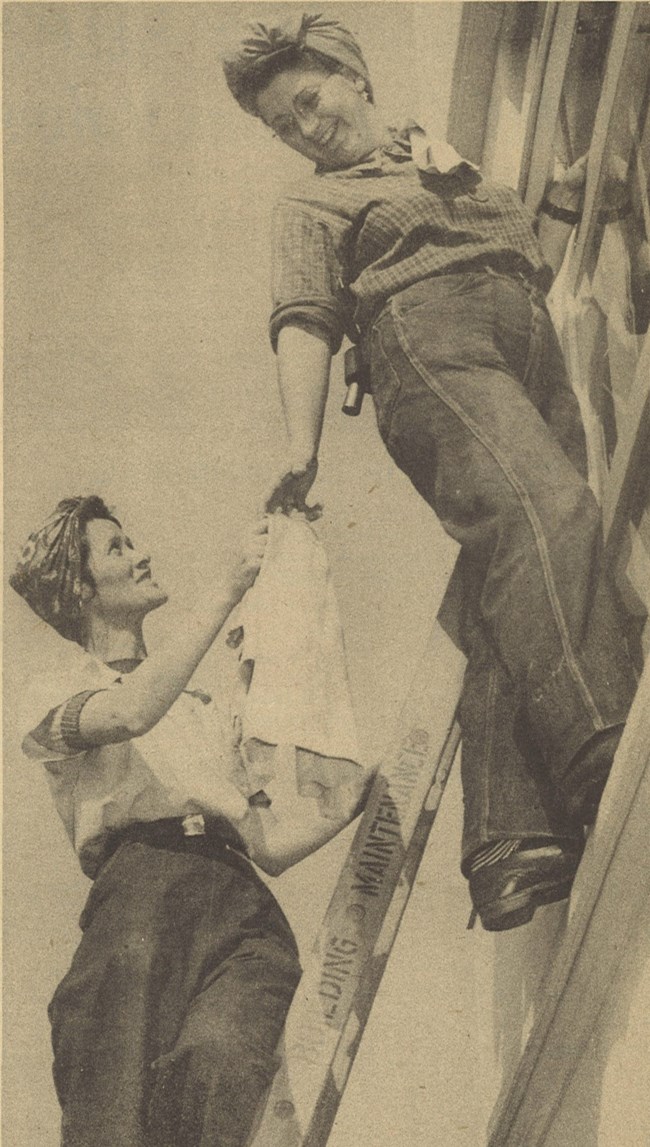

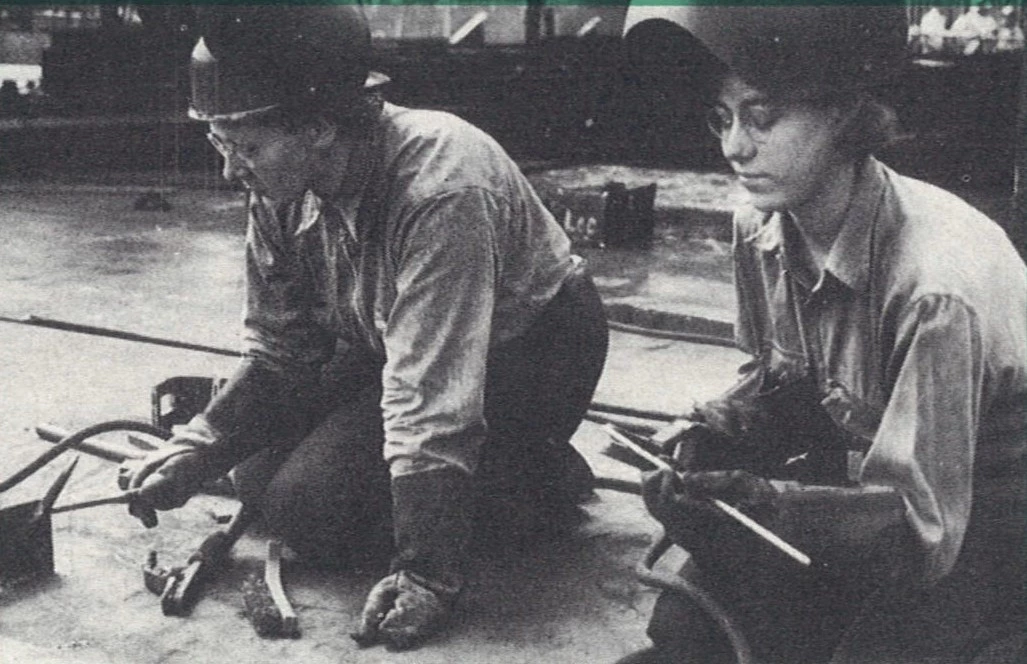

World War II changed the way women worked. A significant portion of the Kaiser Shipyards' workforce was female. In 1939, before the United States entered the war, 2% of the shipbuilding workforce in the US were female. Fast forward to 1944, and over 31,000 women were building ships just at the three Kaiser Shipyards in Vancouver and Portland.Before World War II, many women self-identified as housewives, working to maintain their homes and raise families. Outside the home, women held jobs as store clerks, office workers, teachers, and more. These women often considered their work as secondary to their responsibilities as homemakers. In Fleeting Opportunities: Women Shipyard Workers in Portland and Vancouver During World War II and Reconversion, historian Amy Kesselman writes, "Women who described themselves as housewives may have been employed before the war but saw their work as temporary or secondary to their family roles."

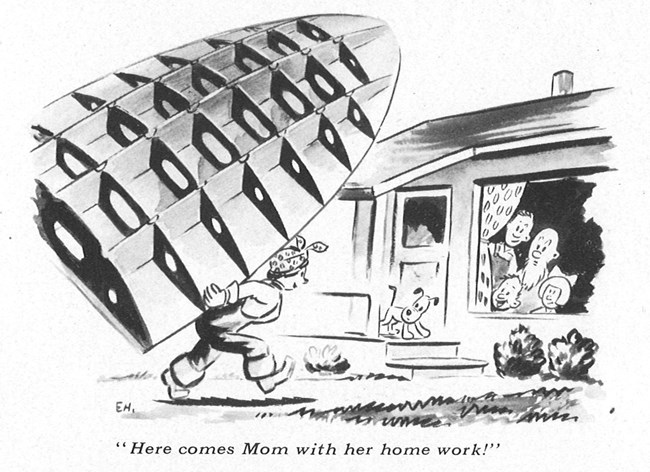

The demand for efficient ship production, coupled with the enlistment of men to serve overseas, caused shipbuilding companies to turn to women workers. Companies used rhetoric to persuade women to ship build, and recruiters canvassed stores frequented by women. Recruiters told women that they should take on new challenges to support the war effort, and that they could work without previous education or experience in shipyards. Women were expected to do "man's work" while maintaining their identities as wives, mothers, or girlfriends who would go "back to the kitchen" once the war was done.

NPS Photo, FOVA 281696

NPS Photo, FOVA 281696

NPS Photo, FOVA 235975

Although women shipbuilders were in unions and received the same pay as men for the same job, sexism was rampant at the Kaiser Shipyards. Many women were sexually harassed by their male peers or supervisors, which often forced them to request transfers to different roles or locations. The local media also treated women welders and riveters as outsiders, or as a temporary solution to the need for wartime labor.

NPS Photo, FOVA 281696

NPS Photo, FOVA 281696

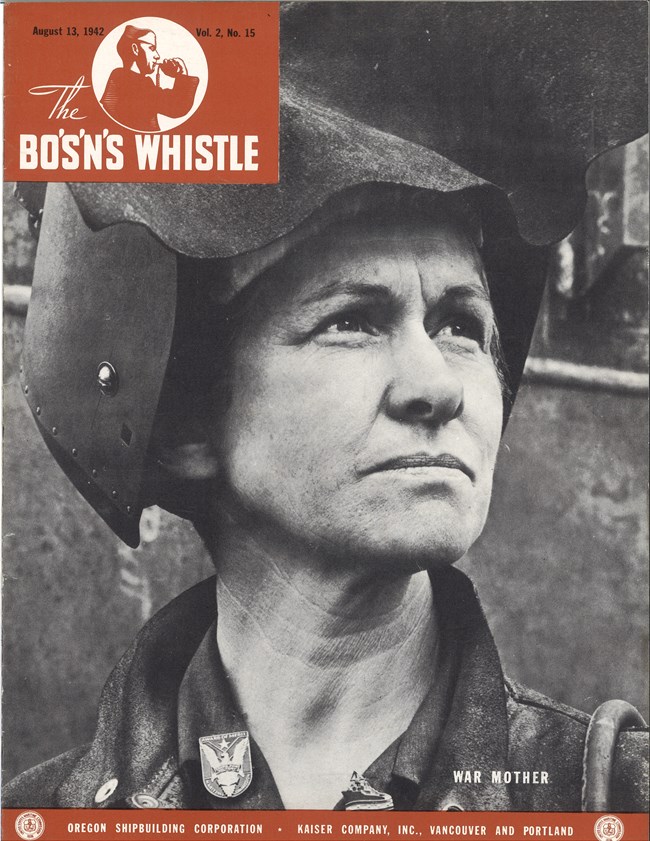

The Bos'n's Whistle

For the men and women working at the Kaiser Shipyards, magazines and newspapers were an important source of information and entertainment. The Kaiser-produced Bos'n's Whistle informed workers of important shipbuilding topics such as the number of ships launched, highlighted different shipbuilding roles, provided safety tips, and inspired competition between the three shipyards to push production.The Bos'n's Whistle began publication in 1941 as a biweekly magazine for the Portland Shipyard. Publication expanded to the Swan Island and Vancouver shipyards the next year. The Bos'n's Whistle supplied personal interviews, shipyard photography, coverage of events like picnics or boat launchings, shipyard sporting competitions, and shared workers' stories.

NPS Photo, FOVA 281696

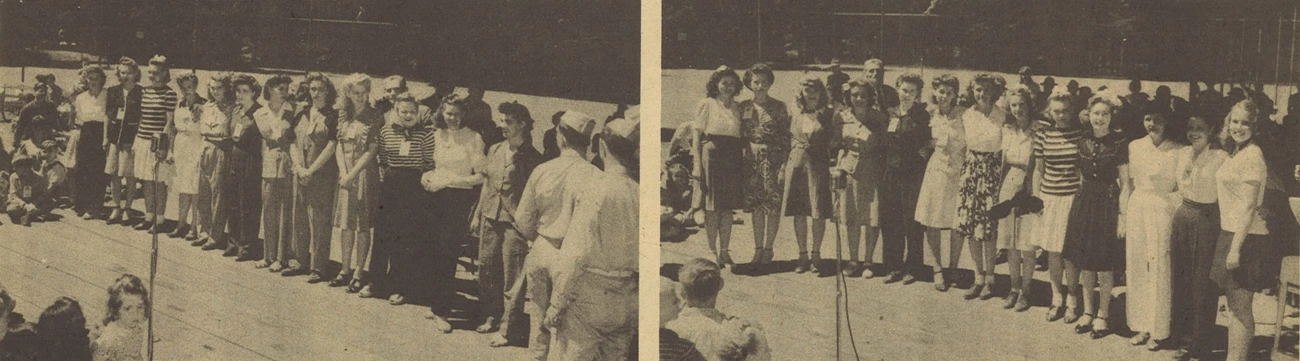

Articles about women shipbuilders often pointed out their attractiveness, describing them as the shipyards' "pin-up" girls. Pageantry and modeling were common features in the Bos'n's Whistle. Objectification served as a reminder that women were working in a sphere traditionally dominated by male workers. The Bos'n's Whistle regularly made reference to traditional roles for women, indicating that shipbuilding would be only temporary work for women. At the same time, the Bos'n's Whistle provides a unique view into the lives of women workers.

NPS Photo, FOVA 281696

NPS Photo, FOVA 281696

She's pretty and attractive, but don't mistake her for a softy. Nora Leola O'Brian, Swan Island guard, is an expert pistol shot and has seen considerable service with the Portland Police Department and as a government agent.

About her job of protecting women in the yard, she has this to say: "Most of them are here from a patriotic desire to take their place in the War Effort. They are all eager to help, and have become accustomed to come to me with their problems. Many difficulties are thus averted at their source."

Stubby Bilgebottom, shipyard photographs, interviews, sports, and all other aspects of the Bos'n's Whistle magazine remained as it reformatted into a weekly newspaper in 1944. Each Kaiser Shipyard had its own edition of the Bos'n's Whistle newspaper. The newspaper often highlighted individual shipbuilders by describing their roles in the shipyard and what their lives were like outside of work. From its beginning as a magazine to its final publication as a newspaper in 1946, it circulated over 4 million copies in total.

After the War

Demand for warships slowed as the war came to a close. It became obvious to the Kaiser Shipyard workers that the war would soon end, and many of America's shipbuilders would have to find new work. In the months after victory was declared in Europe in 1945, thousands of workers were faced with the decision to leave, perhaps returning to their pre-war homes, or staying to make their homes in Portland or Vancouver.Vancouver and Portland formed postwar planning committees as early as 1943 to combat employment concerns and prevent people from leaving the region. However, many of these committees excluded women. As the war ended, women were laid off at higher rates than men. Although women's work in the shipyards was vital to the war effort, it was evident that women's labor was no longer wanted. The Bos'n's Whistle interviewed women workers on their postwar plans, and many responded that they would become housewives, despite the desire by some to remain in shipbuilding or a different field of work.

NPS Photo, FOVA 281696

NPS Photo, FOVA 281696

NPS Photo / M. Huff

About the Collection

Many of the images in this article come from Fort Vancouver National Historic Site's collection of Bos'n's Whistle magazines and newspapers. These archival collections are invaluable to aiding our understanding of the wartime experience at Vancouver, Washington's Kaiser Shipyards.In summer 2024, a recently donated collection of Bos'n's Whistles was processed into the park's museum collection by American Conservation Experience Collections Assistant Intern Tara Gibbs.