Part of a series of articles titled The Williwaw Newsletter.

Previous: Williwaw April-May-June 2020

Article

Courtesy of Karen Abel

The fight against COVID-19 has been a real struggle. Our daily lives have changed in ways we never thought possible. As we work to adjust to the new realities facing us at home, school, and at work we, the editors, wanted to take the opportunity to share stories of those medical professionals who kept our boys on the Aleutian Islands fighting fit.

Medical professionals and first responders saw all sorts of injuries, from battlefield wounds and even more cases of trench foot and frostbite during the Battle for Attu to seriously banged up pilots who crash landed on and off the airfields in the years following and soldiers and sailors who battled psychological demons and the Aleutian Stare. The doctors and nurses – yes, there were indeed nurses on the islands, but mostly on Adak – served our boys well, and we couldn’t think of a better way of showing our gratitude for them than by sharing their stories with you.

Just as before, we are still accepting letters and look forward to hearing from you. Until next time, be well.

--Karen Abel, Joshua Bell, and Rachel Mason, editors of the Williwaw

Robert Fleury, 94, of Portland, ME - April 21, 2020 - Covid-19

William Lynn “Bill” Miles of El Dorado, AR - April 30, 2020

Mark Dowd Baker, 94, of Prospect, CT - July 30, 2020

Alvin Barta, 97, of Lincoln, NE - May 31, 2020

Leonard Ray Shackleford, 97, of Tupelo, MS - June 9, 2020

Rocco “Frank” Tenaglia, 96, of Hyannisport, MA - July 4, 2020

Kenneth J. Miller, 101, of Barron, WI - July 18, 2020

Edmund Herbert Wachter, 99, of Harwich Port, MA - June 28, 2020

Harold Cross, 98, of Richmond, British Columbia, Canada - May 15, 2020

The Aleutian WWII National Historic Area recently received the following inquiry from Richard Harrison:

My father (LTJG Charles A Harrison) served with the U.S. Navy in WWII as a communications officer on Tanaga Island in the Aleutians. As a recently retired professor at UT Dallas, I am now seeking more information on the location of his posting.

I am having trouble finding information online about the U.S. base at Tanaga in WWII, including history and detailed maps. From what my father told me, it was supposed to be a secret so the Japanese would not know about it since it was so close to Attu and Kiska, but this no longer serves any purpose. Yet information on this WWII base is extremely sketchy. Are there any sources I can consult for details on this outpost and its operation, or any information you can provide? A detailed map of Tanaga, with the location of the base and names of lakes, etc., would also be very helpful.

If any of our readers have any information about the U.S. Navy base at Tanaga Island in World War II, please let us know. You may reach Richard Harrison at harrison@utdallas.edu.

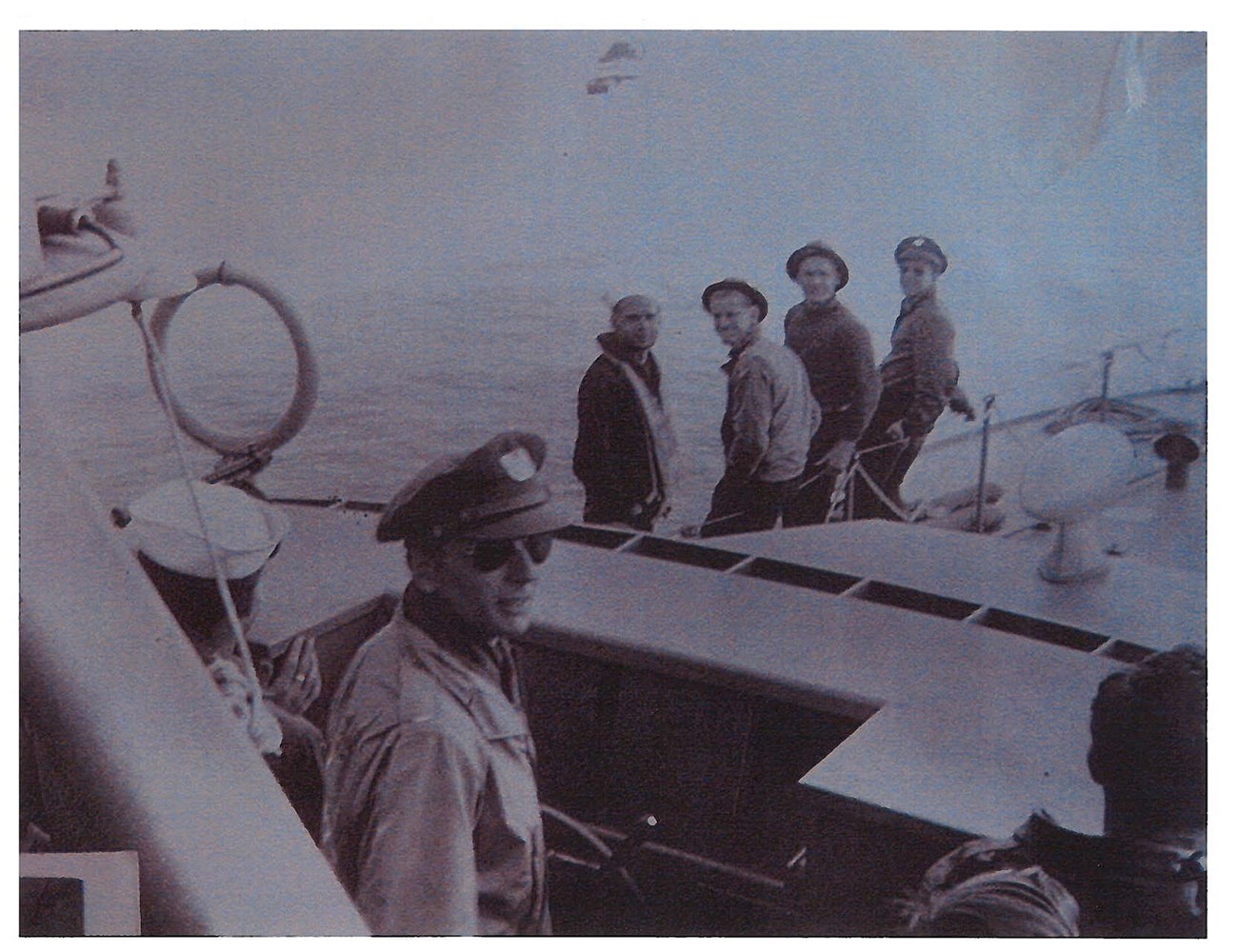

Courtesy of Bill Green

Every pilot who crashed in the Bering Sea knew one thing was certain: they only had about 20 minutes in those icy waters before they would breathe their last breath. For most pilots who flew, the threat of being shot down while somewhere over the Aleutian Islands was, perhaps, the furthest thing from their minds. Not being able to find a place to land was another thing all together. With constantly changing weather conditions, fog thicker than pea soup, and Williwaws that blew in seemingly out of nowhere, the threat of not making it back to solid ground was real.

Wilbur “Bill” Green was already familiar with Alaska when the United States entered World War II. He was born in the lower forty-eight but made his way to the Alaska Territory at the age of 18 in pursuit of a job closer to his father in Fairbanks. He took a job at a gold mining operation as cook before leaving to study administration and biology at university.

Bill was 20 when he enlisted in the Army in Ketchikan, Alaska. He had always liked the sea and saw an opportunity to serve with a small and unique organization within the United States Army Air Force, The 10th Emergency Rescue “Crash” Boat Squadron (ERBS). This group of seafaring soldiers had a critical mission: get downed pilots out of the water as fast as possible. He excelled at his training in Louisiana and California, and when the squadron of crash boats sailed on their month-long voyage from the warm California Pacific coast for the Aleutian waters, he was a sergeant. The squadron arrived shortly after American and Canadian forces landed on the island of Kiska in August of 1943, which the Japanese, unbeknownst to the Allies, had abandoned only weeks earlier.

Bill’s performance earned him a series of quick promotions, and he soon got his commission in Ketchikan as First Mate, making him responsible for a number of duties including navigating around the islands. Excelling at this, he was given his own boat and the rank of Chief Warrant Officer. Crews in the 10th were generally constituted of fishermen who were familiar with the coasts of Alaska, and most skippers could choose their own crew.

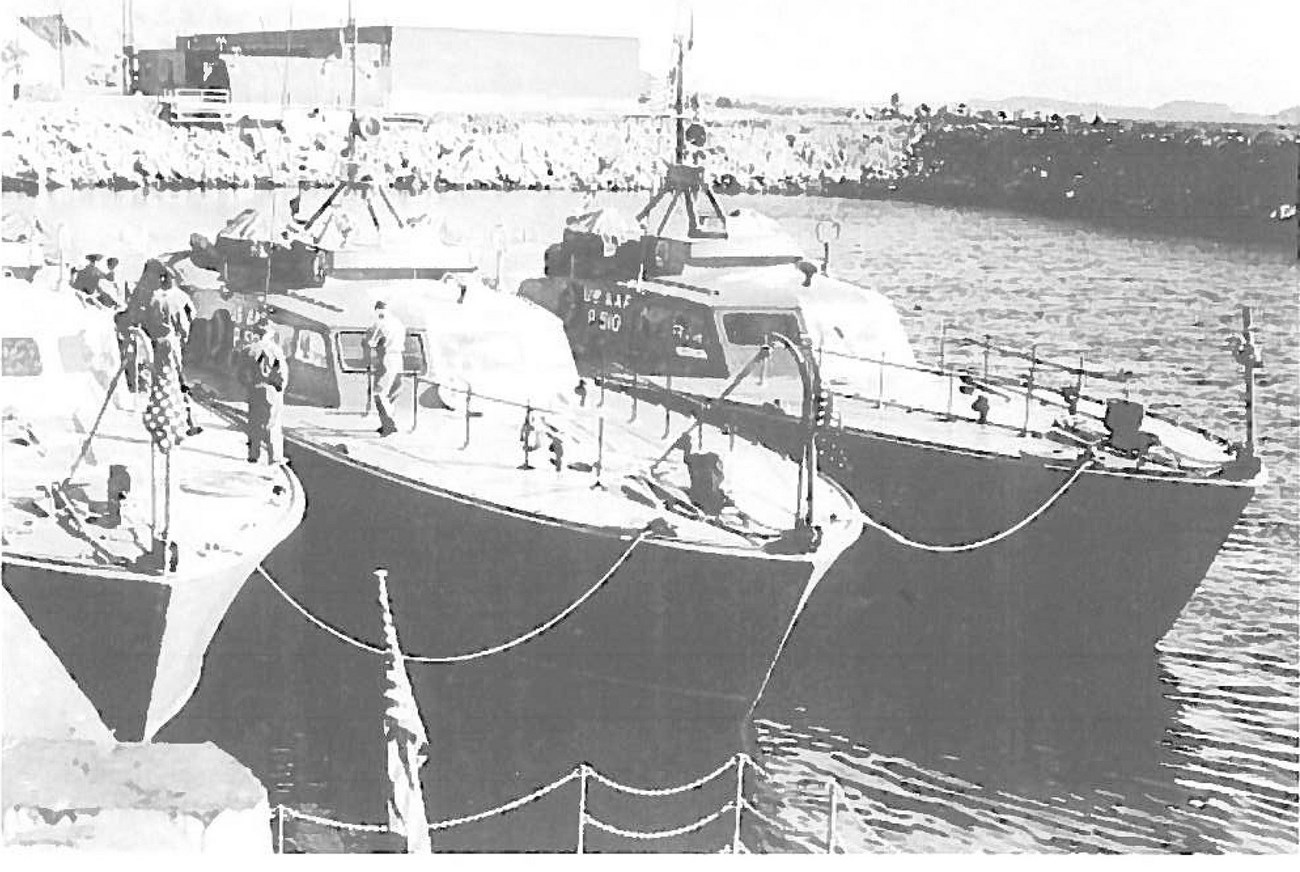

Courtesy of Bill Green

The crash boats were either 104-foot or, later, 85-foot PT boats that were converted for air-sea rescue operations that could cruise at 30 knots. Unlike their counterparts in the Navy, these boats did not carry torpedoes. Of special importance, each boat carried two medics. The crew rotated their schedules; half the crew would be on, while half the crew was off. Crew members had a habit of sticking with their assigned boats, and getting replacements was a rare event.

Fierce weather conditions kept the 10th ERBS busy. Airfield towers along the Aleutian chain were in direct communication with the dozen or so crash boats of the squadron and were able to dispatch them as soon as they had a distress call from a pilot. Without radar, pilots had to depend on the less reliable direction finders to make their way back to land.

Bill and his crew were assigned to Adak upon their arrival to the island chain and were soon busy carrying out their mission. Lucky pilots managed to crashland their aircraft on the shorelines. These were the easy calls to answer. The harder calls were finding aircraft and crews at sea. On one occasion, Bill and his crew plucked 25 men out of the water after their plane went down when they were being transferred from one island to another. Even without the Japanese firing at them, crash landings could be deadly, even if the crash boats were near. According to Bill, “We got some of the bodies, we’d pull ‘em up, and the blood all over the deck was so thick it was hard to walk, and I had to get the crew to wash the blood, so we could finish the job, and then we would turn what body parts we had in to the military to be -- try to be identified.”

When the Japanese returned to harass Attu by air, Bill and his men were there. Their boat in the harbor zig-zagged at high speed, so they would be a harder target to hit. The flight of Japanese aircraft strafing and bombing managed to miss the bigger ships in the bay and didn’t even bother trying to attack Bill and the crew of P-510.

Courtesy of Bill Green

Sometimes pilots didn’t get very far from the runway before having to ditch into the sea. On one occasion, a B-25 Mitchell ditched right in Massacre Bay. P-510 responded quickly, and the crew went over in a raft to pull the aircraft crew from the water. Others were less lucky. The further away from the island you were the longer it would take the crash boats to get there, and there was always the wild card: weather. As Bill put it, “Some of them were so far out, you couldn’t get to them.” On more than one occasion, he and the crew were called back because of uncooperative weather. When the distance was too great or the weather too bad, downed aircraft crews had to rely on destroyers and submarines that dotted the path from the Aleutian Islands to the Kuriles to serve as lifeguards.

Knowing that the crash boats had their backs should something go wrong, pilots regularly showed their appreciation to the crews, forming a bond between the two groups. During down times, which were quite frequent, Bill’s crew would read or bring the pilots out on fishing expeditions.

The presence of these crash boats along the Aleutian Islands undoubtedly saved dozens if not hundreds of lives and, unofficially, provided opportunities for much needed recreational opportunities. Their dedicated crews were made up of “interesting characters,” remembered Bill, adding that he “was one of them.” He never had any complaints from or about his crew, and he was pleased to say that he was “very proud of them.”

US Navy via AP

By Karen Abel

In 2020, the world has struggled through a pandemic of record proportions that has affected every one of us in one way or another. The World War II-era had its share of widespread diseases as well. Strangely, though, in Alaska the unforgiving weather conditions--often referred to as the real enemy--were as much as an ally as an obstacle when it came to contagious illness. The territory’s remoteness, size, rugged landscape and severe winter conditions actually provided a defense against common diseases found in other campaigns; malaria, typhoid, dysentery, and even venereal diseases. (If you have heard the saying “In the Aleutians, there is a woman behind every tree,” you get my drift). Besides the casualties inflicted in the Battle of Attu, overall, the Allies in the Aleutians were a healthy bunch of troops. That is not to say that the 7th Battalion medical units that were spread thinly across the broad Alaska landscape did not get a run for their money. The vastness of the land presented many more serious challenges, especially when it came to providing care and evacuating the badly wounded and gravely ill. The medical units were plagued with continual personnel shortages, the absence of essential supplies, and distance from equipped hospitals. They amassed casualties faster than they could handle them. All these things tested the tenacity of medical unit staff. When it was all said and done, though, the fortitude and competency of the medical units prevailed. They did their jobs and did them well resulting in a presidential citation and forever earning the respect of other Army divisions where respect had previously been lacking.

The first World War II-era Army medical personnel in Alaska appeared in 1938, long before the campaign began. The medical unit consisted of two officers and 20 enlisted men who served the territorial garrison at Chilkoot Barracks near Skagway. By 1941, there was an influx of new bases. Navy bases, each protected by an Army, sprang up at Sitka, Dutch Harbor and Kodiak. There was a new Army base at Fort Richardson, near Anchorage. A network of airbases at Elmendorf (Anchorage), Fairbanks, Ketchikan, Yakutat, Seward, and Nome now increased the Army garrison to 21,500. This rapid growth continued. By June of 1942, six more posts had opened up, increasing troop load to 51,000 and eventually reaching 94,000, more than the civilian population of the entire state.

US Army

The growth of the bases far surpassed the growth of the medical units. Throughout 1942, the distances between detachments also caused the medical units to have personnel shortages unparalleled to other Alaskan shortages, of which there were many. The newly appointed Chief Surgeon, Col. Luther R. Moore, MC, who had long served as an Army officer in the territory, had to decide how best to man such a scattered spread of 21 of posts. His solution resulted in drastic fragmentations of units and in some cases their complete disintegration. In a normal situation, the medical detachment would be split up into medical sections and each section would attach itself to an infantry battalion. In many cases, however, the Alaskan landscape demanded that one infantry division be split up into several separate posts; the 138th, was split between eight locations. Therefore, the Alaska posts were frequently understaffed and continually faced the dilemma of choosing which post to send the unit’ few dentists, pharmacists, and other medical personnel.

The hospital system was equally strained. The scattered stations would not allow for centralized hospitals. Instead, Moore decided to set up unnumbered station hospitals that could handle at least 5% of the troop load at that particular post. By 31 May, 1942 he had 100-bed hospitals at Annette Island, Yakutat and Ladd Field, a 600-bed hospital at Fort Richardson and station hospitals at Sitka, Kodiak, Dutch Harbor, Seward and Nome. He also added 50-bed hospitals at Juneau and Cordova, a 100-bed facility at Naknek and larger station hospitals of 500 at Cold Bay and Umnak. These facilities were not just for Army soldiers but also served airmen as well as some sailors and Canadian and Russian allies.

By the end of September 1942, relief was on the way as numbered Station hospitals were assigned to Alaska and support from the United States started to arrive. With that came the opening of the largest hospital in the Aleutians, the 179th Station hospital on Adak. The hospital consisted of several Quonset huts, each one with a designated function. By the time of the landing on Attu, the 179th Station hospital had a 1500-bed capacity.

Courtesy of Eleanor Burcky

Courtesy Hanna-Call Collection, University of Alaska Fairbanks

Medical personnel had a rough go at it on Attu. The Battle of Attu was miserable on all levels. The medical units involved in the landing suffered through conditions unimaginable to most. Those personnel won hard earned decorations for work that would have been routine anywhere else. The Army made its first amphibious landing upon a hostile shore and suffered casualties proportionally as heavy as any in the entire World War II Pacific struggle.

Under Lt. Col Robert J. Kamish, one platoon from the collective companies of the 7th Medical Battalion was assigned to a regimental landing team for which they would provide care. The battalion medical sections, dressed in the same ill-equipped attire, would land with the fifth and sixth waves to set up and operate the aid stations. As the battalions moved forward, the aid stations would follow. With the exception of the collecting platoon, each aid station went ashore in the first wave with the combat unit they supported to gather the wounded and administer first aid. Their litter-bearers followed to evacuate the aid stations and bring the wounded back to the beaches to the 14th (Southern Landing Force) and 20th (Northern Landing force) Field Hospitals which were busy setting up the initial small hospital and holding facilities; pitching pyramidal tents in ankle or knee deep mud. They were also split into three platoons, each capable of operating independently as 100-bed holding facilities. When that was established, the last companies to come ashore were the clearing companies which were also divided into two platoons in support of the major invading forces. The shore party medical sections would take over care of the wounded on the beaches, transferring the more serious cases to the ships for evacuation to Adak’s 179th Station Hospital where Eleanor Burcky and her unit would take over. This freed up the field hospitals units to advance when so directed by the landing force commander. By the end of the fighting the shore hospital at Massacre Bay would house 443 wounded.

For the medics towards the front lines, supply and evacuation proved to be a nightmare during the first week of heavy fighting. Because of the boggy mattress-like tundra of the Aleutians, and complete absence of roads, every supply and every piece of equipment needed to be hand carried to the front from the unorganized chaos of a supply dump on the beaches. Litter-bound casualties had to be carried, mostly at night for protection, through the difficult unforgiving terrain for hours until they could reach proper care. Injections of morphine syrettes, introduced on Attu, were the only thing that would get a soldier through the ruthless haul. Litter-bearers endured back breaking treks up and down the rocky snowy slopes of Attu, without cover and under sniper and machine gun fire. They were completely exhausted by the time they reached the station. Recognizing this, officers were forced to bring additional men, from wherever they could find them, into the squadron, increasing the squadron from initially four to six or eight men.

Finally, by May 20th, the going got a little easier and greater order emerged. The 50th combat engineering company-built roadways, allowing supplies to be delivered quickly and more forward field hospitals to be set up to care for the wounded. The medical units also developed slides to help bring the patients up from the steep elevations where they could be loaded on trucks and brought to the shore hospitals.

In the days before the final Japanese bonsai attack, U.S. forces were fighting on a ridge west of Chichagof Valley and collecting platoons were moving into the area to evacuate the wounded using a slide that led up to the clearing station on Engineer Hill. On May 28th, seeing that the battle was almost over and that the threat was contained far enough away, the clearing station advanced up the valley taking over one of the relay points, leaving behind a few personnel to man the old site on top of the hill. Little did they know that on May 29th, armed with rifles and bayonets on long poles, the remainder of the Japanese garrison would charge through the front lines and overrun American positions in the Chichagof Valley, including the medical installations, slashing their way into tents filled with patients. Many were stabbed to death through their sleeping bags not having even a chance to evade the attackers. With many escape routes blocked by the invaders, the medics lay unarmed and helpless. At that time, Army medics did not carry weapons, something that changed as a result of their experience on Attu.

By the time the Japanese insurgence reached Engineer Hill, the 50th combat engineering company had formed some type of counter attack and by sunset the enemy had retreated. The damage was done. The clearing stations, still located in the ravaged valley floor, began moving their causalities by the tractor load up the hill and onto the beaches. A total 228 American wounded would make that trip.

Besides a few pockets of enemy fighters still remaining, the battle was over. Through the entire battle, 15,500 Allied soldiers fought on Attu. Of this number, 549 (1 in 28) would die on this desolate island. Those wounded in battle numbered 1,148, and a further 2,100 would suffer injuries related to the other enemy, the climate. The medics themselves suffered losses; 32 were killed and 58 wounded. or 7.5 percent of the medical personnel during the enemy’s final charge. The 7th Medical Battalion dealt with casualties proportionately as heavy as any in the entire Pacific struggle and they did this while understaffed and in the most abominable conditions.

Deservingly, the presidential citation given after the battle hailed the Medical Battalion’s “gallant efforts and its achievements in evacuation under fire” (McNeil, n.d.) Even more, the medical battalion finally earned respect from its infantry comrades. “The Battalion (Medical) Command is proud that the line soldier, notoriously contemptuous of the Medical Corps, has nothing but praise for its members since the operations on Attu” (Kamish, n.d.) Nevertheless, each medical personnel there earned much more than the recognition that followed.

US Army

Hard lessons were learned on Attu, in every unit and in every branch. The lessons learned, many of which could have been avoided, would be used in Operation Cottage on Kiska and in every other Pacific Island battle going forward.

It was a damn costly lesson, though, as 71 of every 100 soldiers had been killed or wounded for every 100 defenders on the island; only the Battle of Iwo Jima was to exact a proportionately heavier toll. The total number of American casualties outnumbered the whole Japanese defense force by a ratio of 3 to 2. Let that sink in.

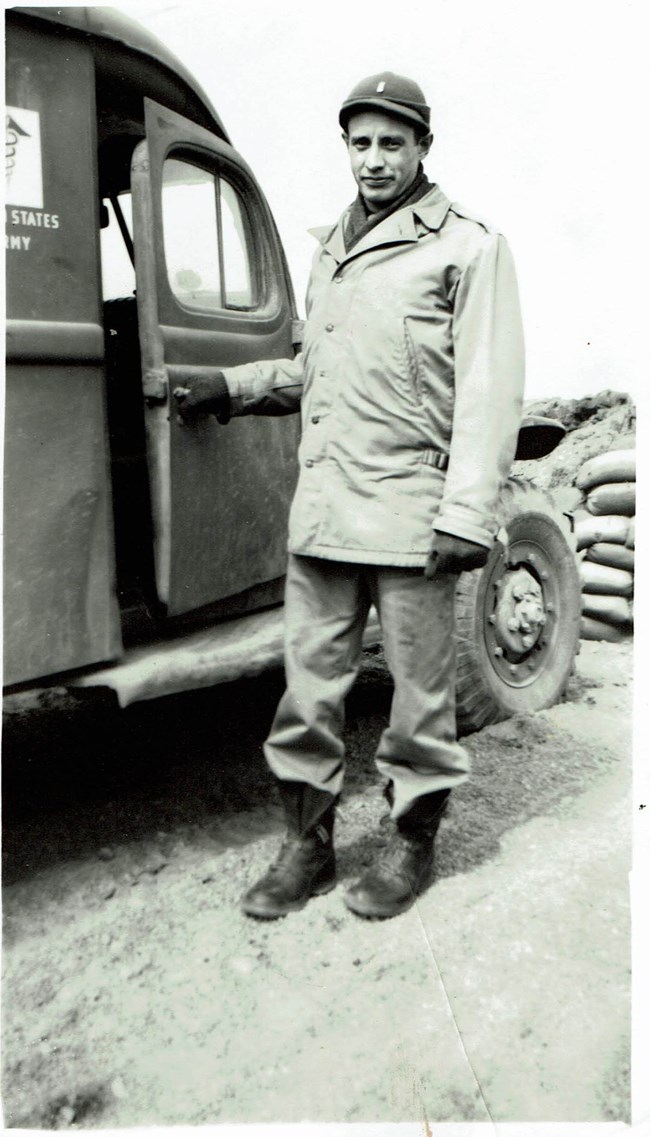

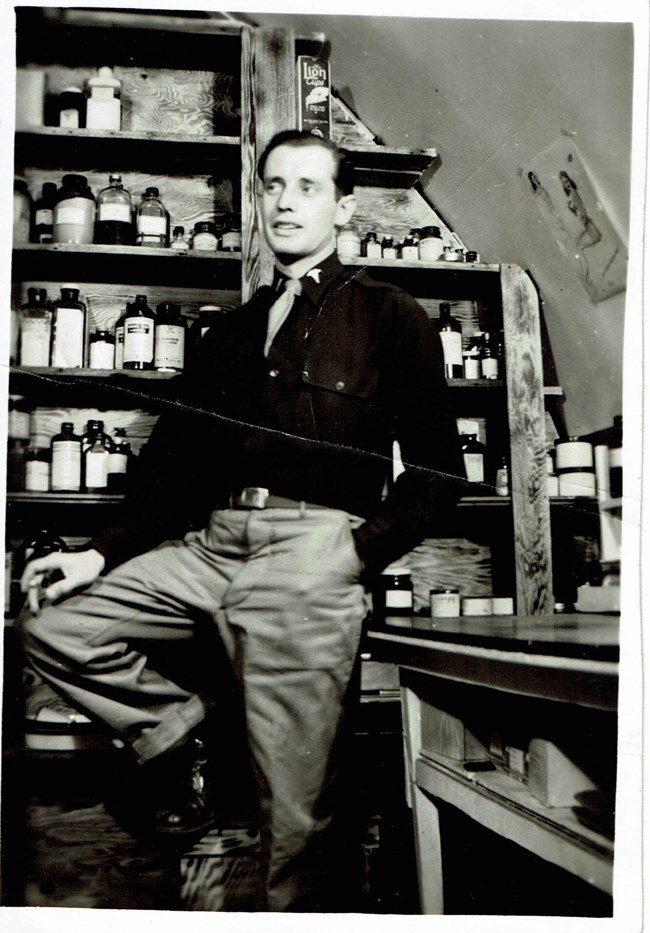

Courtesy of Paul Dietz's daughter, Susan

By Joshua Bell

Paul Dietz was the eldest of five siblings who grew up in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The son and grandson of Lutheran ministers, his calling wasn’t to the cloth, but to medicine. His desire to be a healer led him to Marquette University Medical School. In 1943, while serving a residency in surgery at Ball Memorial Hospital in Muncie, Indiana, he met his future wife, a medical/surgical nurse. Born in 1913, he would have been considered an old man when he received his commission as a First Lieutenant in the Army Medical Corps in November of 1943. He said his goodbyes to his sweetheart and reported to Carlisle barracks for training. An additional two months of training took him to Robins Army Airfield, just south of Macon, GA. It was there that he married his sweetheart in January of 1944.

The couple lived in a small apartment for five weeks before he was called to duty on March 1st. His orders were to report to Salt Lake City. The newlyweds took advantage of this assignment and drove from Georgia to Utah - a long haul before the construction of the interstate highway system - getting as much time together as possible before he was deployed. They had no way to know it, but their separation would last two and a half years.

Paul was attached to the 58th Fighter Control Squadron stationed on Shemya Island. He wrote home on May 9, 1944, the day after he arrived. “There [are] no orderly service around here so we carry our own water supply in and fill the oil container outside and make our own bunks now and then and make an attempt at keeping the wood floor clear. All in all, I’m satisfied. I’d so much rather be doing surgery in a hospital (since the local one is operated by the Ground Forces we merely can admit our patients to it and let them take off the latter – the Army Air Force (AAF) has no hospitals overseas as yet).” He added, importantly, “The squadron mess here is right nearby and the food is better than I anticipated.”

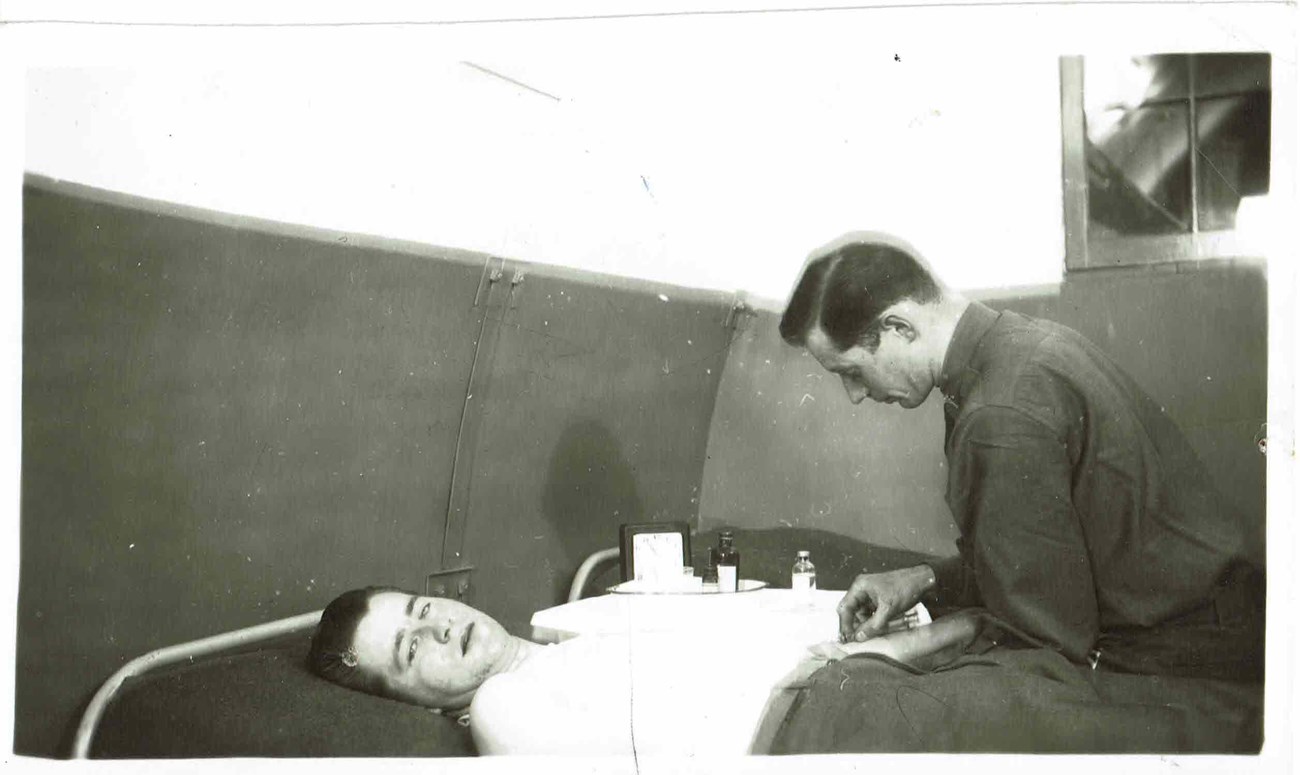

Courtesy of Paul Dietz's daughter, Susan

The doctor’s days began with sick call and mess inspection. Duties would vary depending on the medical needs of the base, but one thing that remained constant was the monthly physical inspection of the cooks and mess help, about twelve men where he was assigned. With the threat of an enemy attack rather low, it seems the biggest threat to the physical well being of the soldiers under his care were sprains and fractures. Occasionally a soldier would need a routine surgery. Sanitary inspections, not his favorite duty, were critical. As he wrote home, “... we’ve got to live a pretty strict life and little slips here and there could soon endanger everyone’s health.”

Something as simple as a shower seemed like a treat, at least to army personnel. The Navy, he wrote home, “which always papers its men always papers” was stationed on the other side of the island, had those along with steam and ultraviolet baths - real luxury.

Sunny days, naturally, helped to boost morale, but the weather took its toll on men. “I think that if the weather were more friendly out here in the Aleutians the men wouldn’t hate the Islands so,” he wrote to his wife.

Courtesy of Paul Dietz's daughter, Susan

That September, he received a promotion to be the second in command of surgery for the Station Hospital of APO 729. The promotion meant doing more doctoring and less inspecting, something about which Dietz was particularly pleased. This excitement came, not just because he would be doing something more to his liking, but because the hospital came with two big advantages, better quarters and better chow.

Following the conclusion of the war, he was reassigned to the 183rd Hospital in Anchorage where he served out the remainder of his wartime commission.

The day he returned home, his wife waited anxiously looking out the window and then the taxi arrived. The view of him getting out of the taxi and throwing his duffle bag over his shoulder was the first real look at him she had in two and a half years. Tears of joy rolled down her face as she heard his footsteps on the stairs.

Deitz remained in the medical field, but enjoyed many hobbies. He was an avid reader, enjoyed tending the yard, and loved music. Music was a large part of his life and he regularly played the piano after dinner and his children would sit next to him on the bench and sing along if they knew the words. His touch and the joy he took in sharing his passion was what made the music come to life.

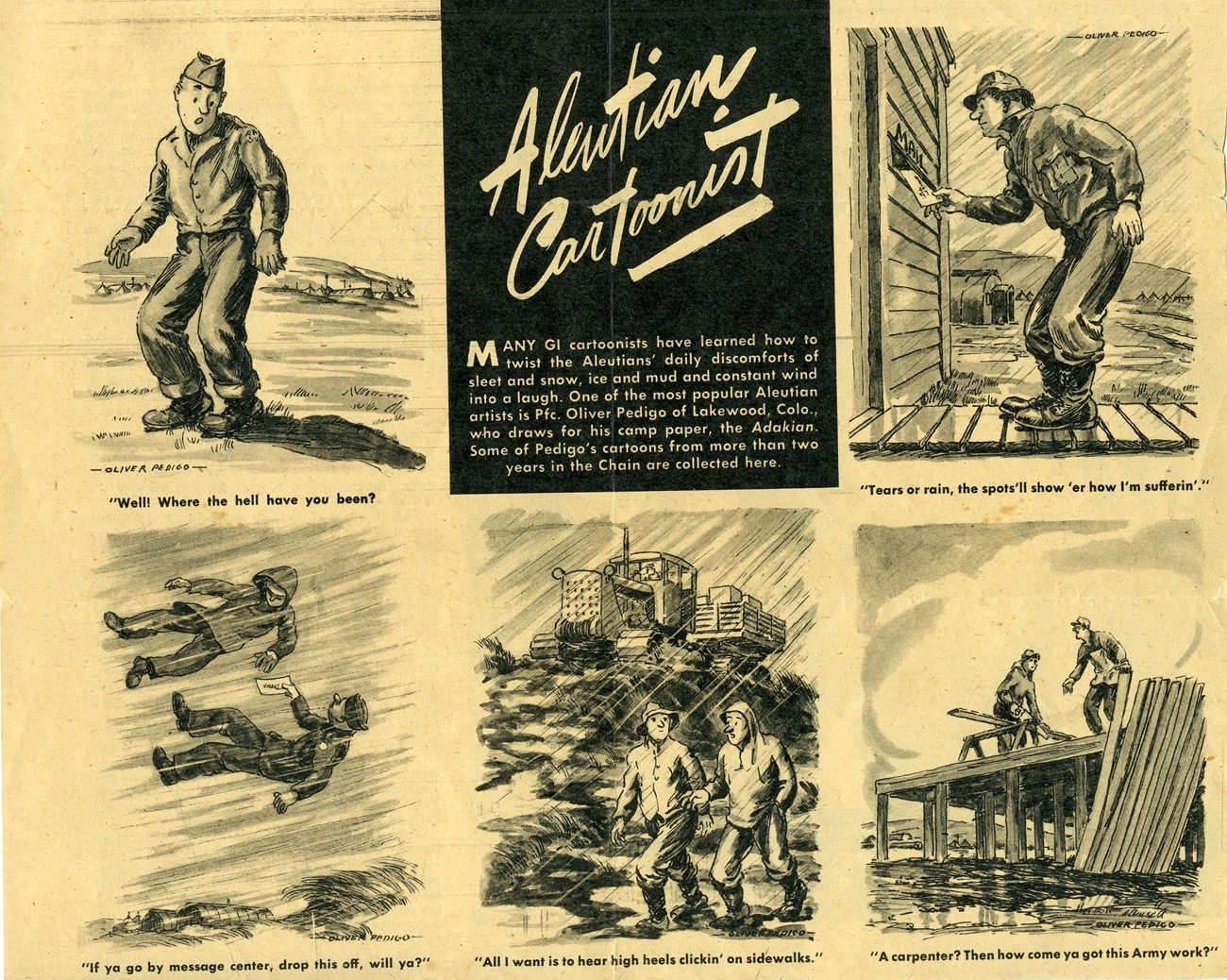

Courtesy of Neil Fugate

Aleutian Islands World War II National Historic Site

World War II

Condon-Rall, Mary Ellen, Albert E. Cowdrey, and Albert L. Codrey. 1998. The Medical Department: Medical Service in the War Against Japan [pdf]. [CMH Pub 10-24]. Pp.148-176. Center of Military History for the United States Army

McNeil, n.d. HUMEDS, RG 112, NARA. “Medical Department in Alaska,” p. 577, file 314.7-2.

Kamish, n.d., HUMEDS, RG 112, NARA. P. 16, file 319.1.

To receive an email notification of, and link to, the newest issue of Williwaw when it is released, please email us to subscribe. If you would like a paper copy mailed to you, please let us know in your email.

You may unsubscribe at any time. We will not email you except when new issues of Williwaw are released (generally quarterly). We will not share your email address with anyone else.

Part of a series of articles titled The Williwaw Newsletter.

Previous: Williwaw April-May-June 2020

Last updated: February 14, 2021