Part of a series of articles titled The Williwaw Newsletter.

Previous: Williwaw October-November-December 2020

Next: Williwaw January 2022

Article

Bruce Hubbard

Air power proved its worth in the Great War (World War I) and was used to great effect in World War II. Aircraft manufacturers competed to put out the best planes they could as quickly as they could. The Willow Run Bomber plant in Dearborn, Michigan led the pack, turning out one fully constructed B-24 Liberator bomber every 63 minutes. These aircraft, along with P-40 Warhawks (or Kittyhawks, as they were called by the Canadian airmen who flew them), P-38 Lightnings, PBY and PBY-5 Catalinas, OS2U Kingfishers, B-18 Bolos, B-26 Marauders, PB4Y-2 Privateers, B-17 Flying Fortresses, and even one B-29 carried crews on critical missions over the Aleutian Islands and beyond, bringing the war to the Japanese. Pilots in the 54th Troop Carrier Squadron with their unarmed C-47s moved men, equipment, and supplies from island to island.

In the months leading up to the Battle for Attu and the recapture of Kiska, air power played a central role. Bombing and scouting missions, which had mixed success rates, were key in determining where the Japanese had dug in.

If living on the Aleutian Islands was tough for allied servicemen, flying over and around them was even more of a challenge. Williwaws are hard on personnel on the ground to be sure, but dealing with a Williwaw while flying? Well...that’s more of a challenge.

This edition of The Williwaw highlights some stories of pilots and planes from the homefront to the frontlines as the Allies struggled to achieve – and then maintain – air superiority over the Aleutian Islands.

As always, we hope to hear from you, the reader. We invite you to share your story or the story of a loved one. Also, if you’re seeking information about the Aleutian Campaign, please let us know about that too and we’ll do our best to get you pointed in the right direction.

--Karen Abel, Joshua Bell, and Rachel Mason, editors of The Williwaw

Congratulations to our centenarian veterans!

Samuel Comella, US Army, 104

Russ Witt, US Army, 101

Harold “Bud” Kysar, Electricians Mate, USS Brazos, 100

David Garland Crawford, 95, of Wasco, California

Charles Arthur Welbaum, 95, of Alpena, Michigan

Alden Bevre, 97, of Abercrombie, North Dakota

John W. Christlieb, 96, of Newville, Pennsylvania

Stafford Chester Mead, Sr, 97, of Holyoke, Massachusetts

Robert Edward Dempsey, 99, of Lexington, Kentucky

Lawrence F. Parolini, 99, of Baltic, Michigan

Otto Clifford Daniels, 102, of Huntington, West Virginia

Raymond L. Cicchinelli, 95, of Waterford, New York

Keith O. Lawrence, 95, of Decorah, Iowa

Roger S. Broessel, 96, of Debuque, Iowa

Sam B. Parham, 99, of Lamesa, Texas

Leon Herbert “Lee” Rathburn, 100, of Williamsburg, Virginia

Albert Southwick, 100, of Leominster, Massachusetts

Jake Hatcher, 104, of Princeton, West Virginia

The only known Aleut/Unangax̂ soldier killed during World War II will finally receive a veteran headstone from the Department of Veterans Affairs to honor his service. Corporal George Fox, US Army, from Unga, Alaska, enlisted before the war began in 1941. He took part in the invasion of Italy and was killed in action on June 1st, 1944, just three days before Allied forces liberated Rome, ending the Italian Campaign.

Courtesy of Mac McGalliard

By Joshua Bell

During World War II, Flying Aces grabbed headlines in papers across the United States. Their stories became the stuff of legend. While on war bond-selling tours back on the homefront, the pilots were swamped by civilians eager to shake hands or to grab an autograph. Many enjoyed celebrity akin to our modern-day movie stars. Everyone wanted to get close. Their stories were made for the movies. Shooting down German fighters while outnumbered or saving their buddy just in the nick of time made for good press and boosted morale.

In Alaska, the air war was just as much about taking the fight to the Japanese who occupied Attu and Kiska as it was surviving a flight in unfathomably bad conditions. Pilots were frustrated by cloud cover that blanketed their ground targets and their home airfields. There was one pilot who seemed more at home flying the iconic P-40 than all the rest: Colonel John “Jack” Chennault. His father, General Claire Chennault, fought alongside our Chinese allies as a member of the all-volunteer Flying Tigers. Jack eventually paid homage to those fighters by dubbing the 11th Fighter Squadron the Aleutian Tigers.

Roy Lee

When Jack was given command of the squadron, he became the leader of a group of young, hotshot pilots who would bring their P-40s in fast during landing. Retired Lieutenant Colonel Bob Brocklehurst recalled the advice about landing he and his fellow pilots got from Chennault: “You’ve got to fly it like any other three-wheel airplane… and stall the plane to fly it. That’s the way you fly it… Not come in hot on two wheels and screech to a stop. That alone, I think, saved a number of lives up in the Aleutians.” Chennault had an “easy, comforting manner,” Brocklehurst remembered of his commander. This disposition served him well, especially when flying in stressful situations with ever shrinking visibility. When visibility shrinks, pilots group up close, so they are less likely to lose each other in the clouds. On one such occasion, the pilots moved in so close, Chennault quipped, “Fellas, I know you have to get in close, but stop trying to get in the cockpit with me.”

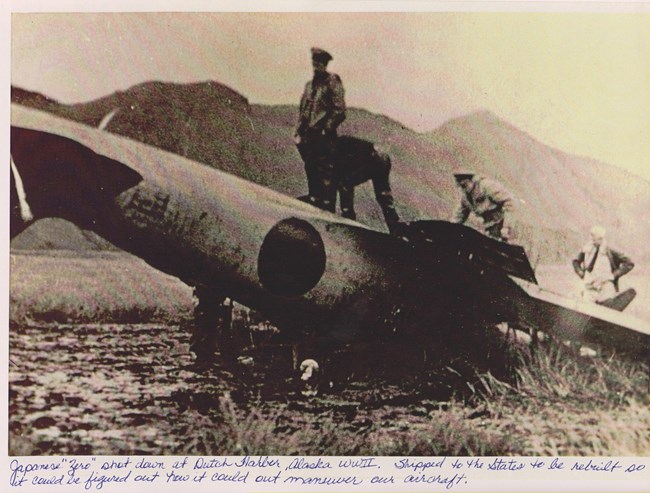

Chennault’s exploits, reported on by the United Press, made newspapers across the country. When they told of how he was the first in his squadron to shoot down a Japanese Zero, he did not brag. “It is always a race among our pilots to see who can get the first plane… The reason I got mine that day is because I had the fastest ship and got ahead of the boys.”

Observations about Japanese pilots and their aircraft were reported in the papers as well. The United Press distributed a story from mid-October 1942, where Chennault led three other American pilots, Lieutenants Pat Deberry of Austin, Texas, George Lavin of San Antonio, Texas, and Gerald Johnson of Eugene, Oregon, on an escort mission to Kiska. Along the way they encountered a formation of Japanese float Zeros that dove straight at them. He and his men had heard about Japanese pilots and their Kamikaze attacks. The American pilots quickly broke their formation, dodging the Japanese pilots. The American pilots regrouped in their P-40 Warhawks and awaited a second run. This time, Chennault had a hunch that if the American pilots held their formation, the Japanese might break first. Given what they’d heard, it was a risky maneuver, but if they succeeded, it would be excellent for morale. The Japanese circled back for a second run. Chennault and the rest of his flight must have been quite nervous as the two groups of aircraft zoomed directly at each other. The American pilots' hands clutched their sticks and throttles ready to take evasive action. At the absolute last second, the Japanese broke formation and whizzed past the cool-handed Chennault. The United Press reported that the Japanese’s “cowardly tricks” had been exposed. Unfortunately, the Japanese actions that day proved to be an exception to the rule.

The winter of 1942-43 saw the Americans’ dominance of the skies over the Aleutian Islands grow, and in March of 1943, it was reported that American fighter pilots who had gained the use of P-38 Lightnings and P-39 Airacobra aircraft claimed sixty-two Zeros with only fifteen American pilots lost; two were shot down by Japanese fighter pilots and thirteen were brought down by Japanese anti-aircraft fire.

It was through the efforts of these and dozens of other American and Canadian pilots that the allies gained air superiority over the Aleutian Islands, even in the worst of weather conditions. Without their regular harassment of Japanese positions, larger bases could have been constructed, and an air war could have lingered, prolonging the liberation of Attu and Kiska.

John Pletcher

by Karen Abel

February 19th, 1941 the very first bomber crew arrived in Elmendorf flying B-18A Bolo’s from the 73rd Bombardment Squadron. They were the advance party sent forth in preparation for the arrival of the rest of the squadron, who were awaiting departure orders at McCord Field in Tacoma, Washington. Captain John Pletcher Jr. was a newly designated pilot, having just graduated 26 July 1940. Pletcher remembers that day well; nine Bolo’s with seven crewmen (pilot, copilot, bombardier/gunner, navigator, radio operator, 3 gunners) would fly the Inside Passage - Prince George, Fort Nelson, Whitehorse, Fairbanks - finally arriving in Anchorage March 1941. His first thoughts of going to Alaska were lukewarm:

“Well, we didn’t particularly want to go to Alaska. We didn’t know too much about it, but we knew that it was like going to the frontier [laughing] and it was pioneering alright. When we got up here, because things that we did, the procedures that we used were, were some that we developed after we got here and some were procedures that had normally been used. And maintaining airplanes was sort of a seat of the pants deal for the maintenance crews using whatever was available and some of it makeshift. It was a really an exploring period for the Air Force. They were learning a lot, we even had local bush pilots come over and talk to flight crews and tell them about things to do and not to do that they had learned by flying out in the bush.”

John Pletcher

Aviation pioneer Bob Reeve, one of Alaska’s best, was a local pilot who stepped in to help the new-to-the-north air corps acclimate, not just to flying in the Aleutians but also to living and functioning in such a cold environment. Capt. Pletcher remembers Reeve teaching them survival skills like how to spot and treat frostbite in their crew. Perhaps this is where Pletcher learned the practice of keeping the heat down in his aircraft and making his crew fly in full winter clothing in case they had to evacuate in a hurry. Their arrival to the then-primitive Elmendorf base near Anchorage, having just been declared operational roughly eight months earlier, came with a steep learning curve.

“Talk about flying by the seat of your pants and by memory of landmarks…. One of the first things they told us to do as a squadron – when we got to Elmendorf when we first came up with the B-18s – go out and fly around and get acquainted with the terrain, so you know where things are up here: where the mountain ranges are, where the lakes are and where the places are where you might be able to land and survive and all that sort of thing, because you may need it. And that’s what we did. So we got to do a lot of sightseeing around Alaska, familiarizing ourselves with the terrain.”

Even six months after Pletcher arrived at Adak in September 1942, there were no radio aids, no radar, no non-directional beacons, and a severe lack of well-functioning radio communication - even if they were allowed to turn it on. Which they were not. So for the most part, it was visual flight rules all the way. And when (not if) it was foggy, you were running on a wing and a prayer.

John Pletcher

Something similar happened when Pletcher transferred over to B-26’s in December of 1941. Major Davis, Commanding Officer of Elmendorf Field, and General Buckner, Alaska Defense Commander, realized that the current 10 serviceable B-18A’s were just not enough nor were they suitable for the long-range missions needed in the Aleutians. They pleaded their case to General Henry ”Hap” Arnold, Chief of Staff, Army Air Corps and Lt General John DeWitt, Commander, IX Corps (Western Defense Command) and eventually they were heard. The B-18’s moved into the role of patrol and training with the 36th and the 73rd received the upgraded B-26’s. John remembers that his B-26 check ride was simply four touch-and-go’s around the pattern! He and his crew were left to learn the intricacies of flying the sometimes unforgiving B-26 on their own.

“My crew had never been in one, so we got in an airplane and they said, “Well, here take this airplane and go and fly and get acquainted with it.” So we took an airplane [chuckle] that we knew little about and flew off down the Copper River Valley and down over, and came up through over Seward and all the way up along the Alaska Railroad. A strange airplane, one that we didn’t know a thing about, but they said, “Well, you’re a pilot you’re supposed to be able to fly anything” – so we did. And a lot of things went that way in the early days of the World War II - a lot of things didn’t go exactly according to the book and according to normal procedure.”

The fact that only a handful of B-26’s were lost, most of those due to combat related action, in this theater is a testament to the skill of the pilots, like John, who flew in Alaska. Notoriously, upon rollout from the factory, the B-26 was proving to have a high accident rating and it demanded a skilled pilot and crew to fly it without incident. I mean, Aleutian weather is bad enough let alone in a plane that had been dubbed the “Widowmaker”? Goodness. Pletcher, though recognizing its difficulties, still enjoyed flying the aircraft:

“The B-26 was pretty fast. If you put the power on it, on a run in you could probably do 250 mph with the bomb bay doors open if you were on a low level bomb run. The airplane would do 300 or better with the bomb bay doors closed and flaps and gear up. It was a pretty fast airplane.

We normally cruised at a little over 200 and on the way back from Attu, on that mission, I had it way under 200. In fact, I had the engines slowed down and manifold pressure cut way back and we were just literally almost hanging in the air coming back trying to conserve fuel, and we had the mixture in the lean position and doing everything we could to save the fuel.”

John Pletcher

Eventually, they too, would be replaced with the much more suitable B-25 Mitchell by January 1943, leaving the B-26’s relegated to patrol duty - but not before seeing their fair share of missions to Kiska and Attu. For an entire year, early on, they were used as combat aircraft and flew missions out the chain. Pletcher narrowly escaped the barrage of Japanese anti-aircraft fire one mission over Japanese Imperial Army occupied area of Gertrude Cove, on Kiska:

“That hole in the side of the airplane was an airplane that I had flown. It was on a mission out to Kiska and they had a ship that was – I think it was grounded – but it was drawn in next to the shoreline in what they call Gertrude Cove. There were two coves out there at Adak - Kiska rather - and they had this one ship pulled inside of it, parallel to the beach, and there was a cliff on each ended in a cliff, about, oh I guess it was about 100-200 feet high. From the photographs that they had of the ship they didn’t know about this cliff, they couldn’t tell about the cliff. So, I and a wing man were sent out to bomb that ship and our deal was to fly over the island and over this bay, over the ship and bomb it on the way out. Well, lo and behold when we came over the land and we were low, we were just about as low as you could get, when we came over that, lo and behold we couldn’t even see that ship because it was hidden behind the cliff. By the time we could see it, it was too late to line up on it and bomb it.

Well, on the way out my ship, which is shown in this picture here [picture 6 and 7], got hit by some piece of artillery from the ground, from the Japanese, and apparently the round did not explode. That came right at the hinge point of the nose wheel door on an angle from the rear to the front, about a little steeper than a 45-degree angle and angling in toward the center of the airplane slightly. So it entered by the hinge and then came out through the side of the airplane further up and in the process it cut out, broke out a stringer that ran lengthwise around the curve of the nose and it curled back the skin on the nose as shown in that picture. That round or shell whatever it was, it may have been a 37mm or whatever, the shell came between the skin of the airplane and the upholstery in the cockpit – the first airplanes had upholstery in the cockpit – and in the process it cut the bundle of radio wires leading to the co-pilots control box which was right at his right elbow. That round would have come probably within at least 6 inches to a foot of the co-pilot’s elbow and it disabled his radio; he couldn’t talk over the radio. So I was unable to contact him by radio but I could holler at him. And that’s how close it came. If it had come one foot closer to the center of the airplane it would have come right through the co-pilots seat. It probably would have knocked out everybody in the cockpit. It would have probably brought us down, so we were just darn lucky that it didn’t come further into the airplane. But it came through and out and there was no evidence of gunpowder burns or anything on the metal on the airplane so obviously it did not explode. It was the just the round going through that tore that hole in the airplane.”

Karen Abel

Karen Abel

John Pletcher Jr. was born on October, 13th, 1915 on a farm near Laird, Colorado and entered the service November 10th, 1939. Alaska was his first operational posting. During his near two-year stint along the chain, John saw time on at least five different bases: Elmendorf, Adak, Umnak, Cold Bay and Nome. In 1943, he was posted to the Lower 48, leaving behind the cute little house on 9th Street (still standing) in Anchorage built by Emil Pfeil, that he rented to house him and his wife, Millie, who had come up in the spring of 1941 on the St. Mihiel to be closer to her new husband.

After leaving Alaska, he began his duty as a B-26 Flight Instructor out of MacDill Airfield in Tampa, Florida and then his own flight training with a B-17 Squadron at Roswell and finally B-29 training in Tucson, Arizona where he eventually took over Command of their operational Training Unit. After the war he went back to farming for a short while only. After realizing it was not as glamorous as he remembered, he moved to Lakewood, Colorado, just west of Denver, to manage his brother’s retail store. Inevitably though, he returned to college to get his accounting degree at the University of Colorado, eventually finishing his career working for the U.S.Civil Service Commission as an investigator granting security clearances for the Atomic Energy Commission. John would live in Lakewood, CO until his passing at the age of 95 years young.

Some of you may recognize the name "John Pletcher." That is because his son, John Pletcher III lives in Anchorage and routinely takes part in many WWII Aleutian Island Commemorative ceremonies flying his U.S. Navy 1944 amphibious Grumman Goose. On the advice of his veteran father, John bought and restored “the Goose” in 1996. In 2017, as part of the commemorative ceremonies marking the 75th Anniversary of the Bombing of Dutch Harbor and Aleut Evacuation the Grumman Goose made the 1600-mile round trip journey to Dutch Harbor in formation with the Commemorative Air Force, Alaska Wing’s Canadian Harvard. Quite the feat for those old birds and quite the honor.

Thank you, John Pletcher, Jr. for your service and to John Pletcher III for your efforts to keep history alive.

Joshua Bell

By Joshua Bell

Captain Red Randall flew just about every aircraft the Army Air Force and Navy had at their disposal. His service was intense and unlike any other in such a short time. In 1941, he was at Pearl Harbor when the Japanese attacked. Soon after that, he was dispatched to Australia and was part of the failed attempt to prevent the Japanese from taking the Philippines. He was captured by the Japanese, but managed to escape. General Douglas MacArthur then sent him on a secret mission to support Chinese Guerrillas fighting the Japanese, where he was captured a second time and managed to escape. He and his friend, Captain Jim Joyce, turned the tide at the Battle of Midway. They were shot down over New Guinea, captured by headhunters, and escaped through the dense jungle occupied by Japanese soldiers. Their unlikely reunion with American forces was followed by a daring raid on a secret airfield. After the Japanese attacked Dutch Harbor in 1942, Randall and Joyce volunteered for a secret mission, flying along the Aleutian Islands. Their failure could have allowed the Japanese to gain a foothold on Adak, or at least that’s how their creator imagined it.

R. Sidney Bowen was born in 1900 in Allston, Massachusetts. His service began as a volunteer in France with the American Field Service during the First World War. He was eventually returned home because he was under military age. This was no deterrent for Bowen. In 1917, he enlisted in the Royal Flying Corps in New York. He crisscrossed North America, training in Canada and the United States, and then was assigned to the 84th Squadron shortly before the armistice was signed. He flew in France, Belgium, and Egypt during his service. On November 12, 1918, he wrote home that his plane had 33 bullet holes in it! More alarmingly, he reported that his flight suit had three holes, which shows he was “in some close action.” Post war, he went on to write for a number of publications, and when the Second World War broke out, he put his skills to use, writing adventure books for young people. His first series followed the exploits of Dave Dawson who served all over the world. Red Randall and Jimmy Joyce were assigned mostly to the Pacific Theater.

Public Domain/New England Aviators 1914-1918; their portraits and their records.

Although he never set foot on the Aleutian Islands, as far as anyone knows, Bowen captured, with fairly good accuracy, the challenges and tribulations, fears, and frustration of flying along the Aleutian Island chain. He accurately depicted the land as desolate. He hinted at the mix-and-match nature of the Army and Navy command composition. He described the weather as “violent gusts of wind” hitting the islands “from all directions, churning the slate-gray waters into a froth and sending moored Catalinas skipping around like chips of wood.” He went on:

A hundred times, one or another of the Catalinas came within an ace of breaking free and being hurled against the rugged shore. But valiant crews saved them each time, and when finally the williwaw spent itself, everyone had blisters, cuts, and chapped hands to say nothing of aching muscles and a new-found hatred of the Aleutian weather.

Aside from those accurate depictions of weather, he also captured the essence of the weather on missions flown along the Aleutian Islands chain. When Randall and Joyce “flew into the soup,” they experienced getting disoriented and ended up landing off their target area. Chasing enemy planes or sighting enemy ships was frustrated by the cloud cover, but when they were in enemy sights, that ever-present cloud cover allowed them to disappear.

Do Randall and Joyce complete their secret mission and live to fight another day? You’ll have to locate a copy to find out!

The collective popular memory tends to believe the fighting that took place on the Aleutian Islands was little more than a footnote, unknown to most at the time, and kept a secret by the military. Books like Red Randall in the Aleutians Islands indicate that this might not necessarily have been true at the time, but rather the result of a preponderance of media, books, and films about larger, more action-packed battles and missions that were popularized following the war. Bowen’s accuracy depicting flying conditions and place names sheds some light on the Aleutian Campaign as something that might not have been as distant from the public consciousness at the time as we may think today.

From the family fireside to far-flung fronts Coca-Cola stands for the pause that refreshes--has become a symbol of those who see things in a friendly light."

Coca-Cola ad published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, June, 1944

by Karen Abel

We have all seen certain watering holes where dollar bills or other bank notes left by their loyal patrons adorn the walls and ceilings of their establishment. Each bank note has a story or tradition behind it. One of those bank note rituals dating back to the mid-1920s was that of the Short Snorter. Its origin is said to come both from Alaskan bush pilots like Ben Eielson, and from Gates Flying Circus performer Jack Ashcroft, who persuaded his agitated boss, well known civilian aviator and barnstormer Clyde Pangborn, to sign a dollar bill for him. On that note, Pangborn wrote “Short Snorter No. 1 Pangborn, August,1925”.

This tradition of signing money was originally picked up by air crews traveling together, but eventually servicemen of all branches adopted this tradition which would continue through the war, at some point transforming into a type of social club: the Grand Order of the Short Snorters.

The name Short Snorter is a spinoff of the old slang expression for a stiff drink: “snort," like a whiskey shot, and “short” meaning less than a full shot measure, which is what a dollar bill might have bought you back then! This play on words would later become a telling piece of its legacy. Funny, I can remember growing up, my sweet little great-grand-aunt, who was born in 1900, would say her remedy for sleeplessness was a “snort” of vodka!

Originally, admission into the Order of the Short Snorters was granted upon the completion of a trans-oceanic crossing where you were required to give each present member of the order one dollar plus a dollar bill for yourself which you would sign along with at least two other members. This newly signed dollar bill would now serve as your membership card, your very own Short Snorter. From that point on, you were required to carry this signed bill, often stored as a roll in your pocket, at all times. This was important because at any moment, another member could challenge you to produce your note and and failure to do so resulted in either a round of drinks on you or having to pay each member present one dollar each! Not sure which is worse… Over the years, new rules were introduced. For example, when challenged, the person who presented the bill with the least number of signatures would have to buy the drinks that round. As you can imagine, this motivated members to get as many names on a bill as possible.

As a service member was posted to other countries, the membership bill would grow. You were required to take a new bank note from that particular country and have it signed by any two Short Snorters members, then tape it to the end of the previous Short Snorter. Needless to say, if you travelled a lot, you would end up with a very long membership card! The longest one on record is 200 ft long, containing over 400-500 bills, owned by Grover Criswell!

Over time though, the Short Snorter became simply a token of good luck and a keepsake of those you met along your travels. By the end of the war, membership to the Order was in the millions and included some big names like General Dwight Eisenhower, General George S. Patton, General Hap Arnold, presidential candidate Wendell Wilkie, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Although it faded somewhat, the tradition did carry over into the 1960s with the Gemini and Apollo crews signing and carrying dollar bills into orbit and suffering the same consequences back on earth if they forgot them!

Karen Abel

There is a remarkable website, www.shortsnorter.org, dedicated to preserving and collecting Short Snorters. Tom Sparks, the site’s founder, was kind enough to let us share some of the most impressive Short Snorters from the Aleutian Campaign, which include bills with the signatures of Hollywood actress Olivia De Havilland and Attu schoolteacher Etta Jones, who had been a prisoner of the Japanese.I have a Short Snorter from my Grandfather’s collection. When I found it several months ago, I suddenly noticed that the dollar bill had names written across it and was titled “Short Snorter”! What a gem. Who else was a member of the club? We’d love to hear your story. Write to us and let us know!

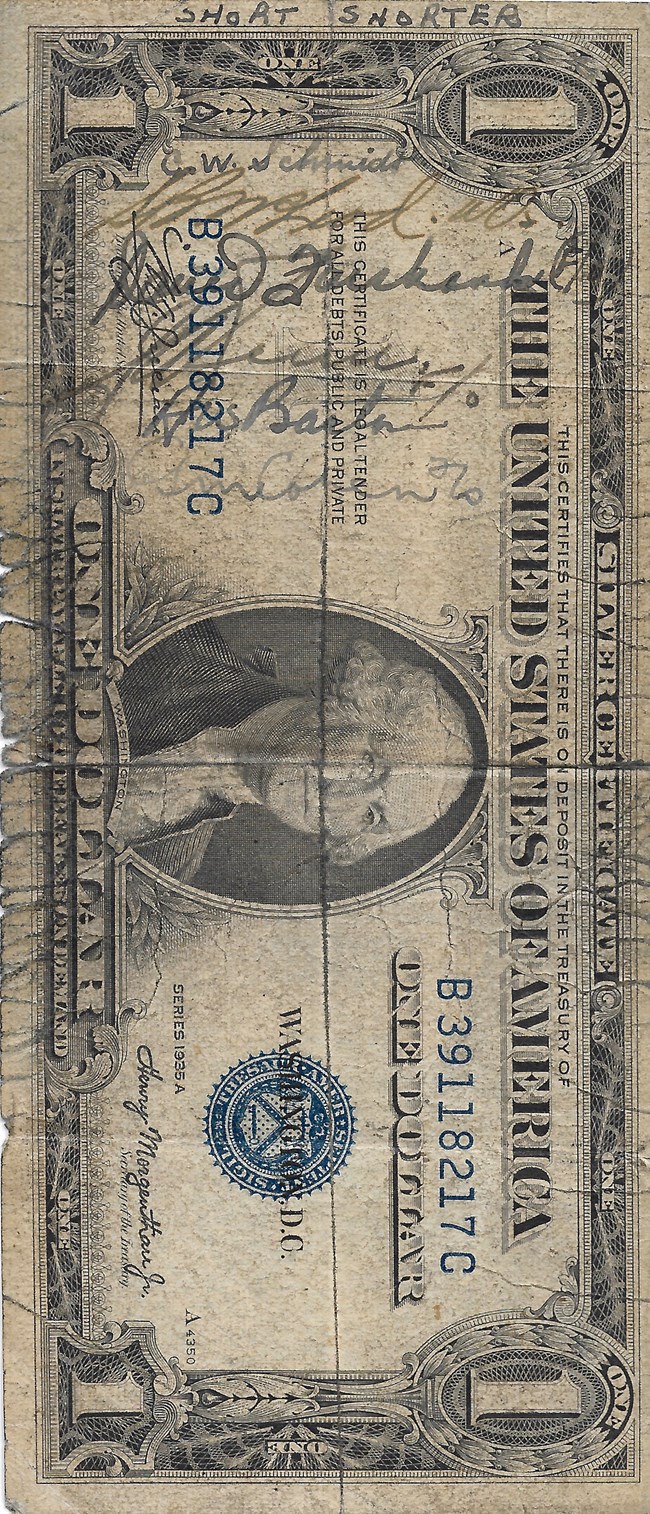

P/O (Pilot Officer) Lynch, my grandfather, listed as the second pilot, boarded a U.S. Navy DC-4 flown by Lt. Com Lyon bound for Seattle. He was finally going home to Canada for his annual leave after one year in Alaska stationed on Umnak, Adak and Kodiak. Listed on the bill were two Canadians—Lynch and SR “Red” McLeod WO2. Warrant Officer I (Pilot) Samuel Roderick Joseph "Red" McLeod, RCAF, was also going home for his annual leave after the same amount of time in Alaska. P/O McLeod would return to Alaska to take part in bombing/strafing missions over Kiska until August 1943 when the squadron was ordered to stand down for duty and return to Canada. For Lynch however, this would be his last time flying over the Alaska waters, as he was posted to Flying Instructor School in Alymer, Ontario to become a flying instructor.I assume the others listed on the bill were U.S. servicemen:

C.W. Schmidt

David Fairbanks F/O

Barton F/O

Ron Coleman F/O

The flight from Alaska to Seattle lasted for 6 hours, 45 minutes.

Jose “Joe” Crosson was the General Manager for Pacific Alaska Airways, a subsidiary of Pan American Airways, when WWII broke out. Pan American contracted with the U.S. Navy and helped the U.S. military with all things Alaska until poor health got the better of him, grounding him from flying. General Hap Arnold liked him so much, though, that he recruited Joe as a civilian working with a group analyzing military operations along the Aleutian Islands. Tom Sparks believes this Short Snorter titled “Attu June 21, 1943” was from one of those trips in combination with previous trips that may or may not have been in Alaska.

Signed by:

James M. Johnstone

O.S. Glenn

Roy White

Howard Thompson

Curvin H. Greene

E.C. Dixon

Willis E. Cleaves

D.L. Jacobs

Buckshot Lien

Roger Q. Williams

Ward D. Davis

Joe Doolittle (Col Doolittle’s wife)

Billy Parker

Hank Hollenbeck

Note: Joe Crosson's original Short Snorter dates back into the 1920s and is signed by Carl Ben Eielson (which would have been before Nov. 1929), H.H. "Hap" Arnold, Mae Post, Ralph Wien, Percy Hubbard, S.E. Robbins, Jack Elliott, Gene Meyring, Harold Gillam, Earl Borlund, Hugh Brewster, and others. This artifact goes back to the origins of the Short Snorter tradition.

Hollywood Actress Olivia De Havilland toured several Aleutian bases in March of 1944; you will see her signature 13th from the top. This lucky soldier, Campbell, seemed to have collected the signatures of all the girls in the USO show. This is an example of how the Short Snorter tradition was adapted over time.

Courtesy of Tom Sparks

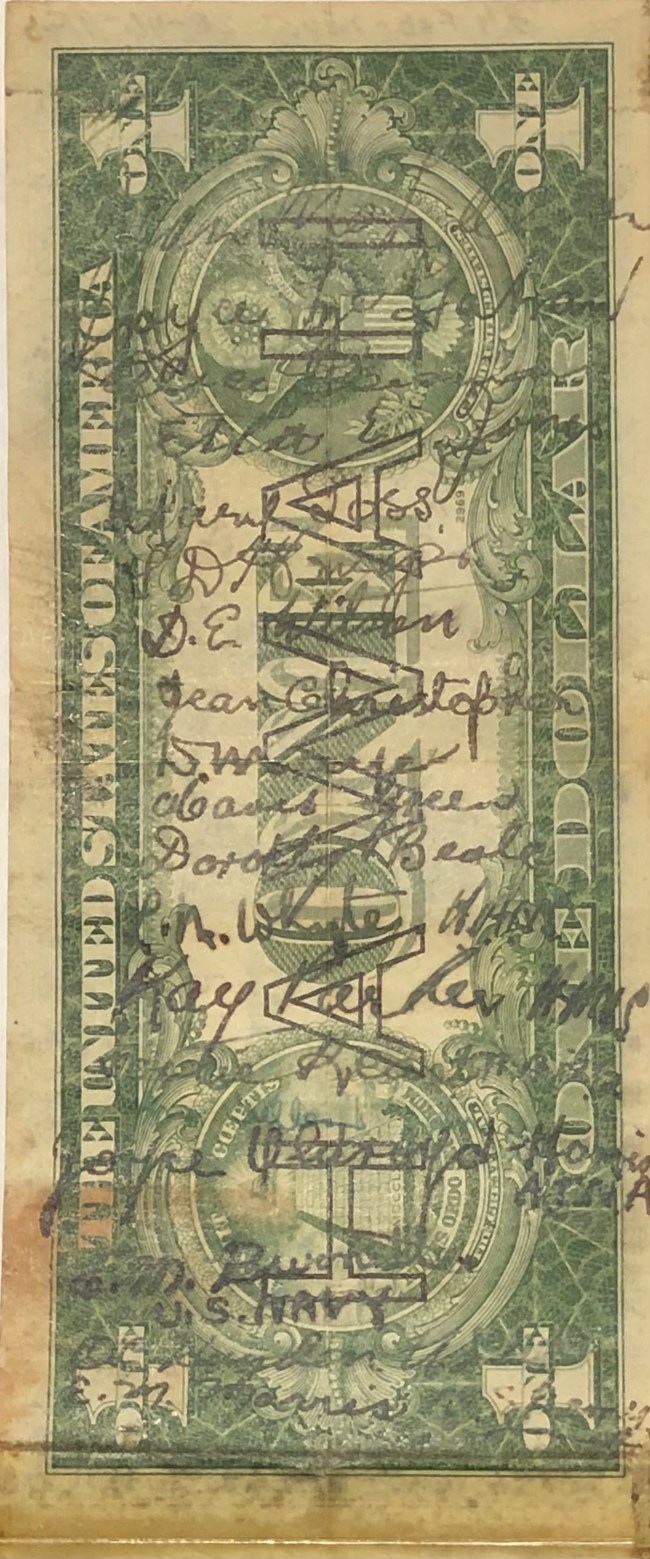

Etta Jones was the schoolteacher who was stationed on Attu with her husband, Foster Jones, when the Japanese captured Attu. She was taken on a boat to Japan and was detained there as a prisoner with a group of Australian nurses who had been captured as part of the Japanese invasion of Rabaul. The women remained together until they were freed at the end of the war. This Short Snorter was most likely initiated on their magical flight to freedom from Okinawa to Manila September 3rd, 1945.

There are 18 signatures, one of them identified as U.S. Navy. Signatures identified on the back of the United States Silver Certificate HAWAII Overprint:

Jean McLellan (Qld),civilian nurse

Joyce McGahan (Qld), civilian nurse

Alice Bowman (Qld), civilian nurse

Etta E. Jones, American civilian schoolteacher taken prisoner on Attu Island

Mary Goss (NSW), civilian nurse

Grace Kruger (Qld), civilian nurse

Dora Wilson (NSW), civilian nurse

Jean Christopher (NSW), Methodist Ministry

Dorothy Maye (NSW), Gov’t hospital

Mavis Green (NSW), Methodist Ministry

Dorothy Beale (Qld), Methodist Ministry

Lorna Whyte (NSW), Army nurse

Kay Parker (NSW), Army nurse

Daisy Keast (NSW), Army nurse

Joyce Oldroyd-Harris (NSW), civilian nurse

??? US NAVY

Mavis Cullen (NSW), Army nurse

91st Bomb Group

Bowen, R. Sidney. Red Randall in the Aleutian Islands. Published 1945 by Grosset & Dunlap.

National Archives

PBS Short Snorters

Pletcher, John. Interviewed by Janis Kozlowski for the National Park Service.

Snark, Tom. The Short Snorter Project.

To receive an email notification of, and link to, the newest issue of Williwaw when it is released, please email us to subscribe. If you would like a paper copy mailed to you, please let us know in your email.

You may unsubscribe at any time. We will not email you except when new issues of Williwaw are released (generally quarterly). We will not share your email address with anyone else.

Part of a series of articles titled The Williwaw Newsletter.

Previous: Williwaw October-November-December 2020

Next: Williwaw January 2022

Last updated: July 21, 2021