Last updated: December 1, 2022

Article

Deer Monitoring at Wilson's Creek National Battlefield

NPS

White-tailed Deer Populations

Deer are one of the more charismatic creatures you can find at Wilson's Creek National Battlefield. It's hard to imagine that white-tailed deer were almost extinct in the early 1900s from overhunting and clearing of forests. Hunting regulations and removal of most of their natural predators has now led to unprecedented deer population growth. Without natural predators, deer can become overpopulated and die of disease and starvation.

Too many deer can also overbrowse trees and other plants. Deer can alter landscapes because they prefer to eat native plants allowing exotic, invasive plants to grow and spread. Large deer populations may also result in more deer-vehicle collisions and deer disperse ticks that can spread diseases to humans.

Why Do We Monitor Deer?

Scientists from the Heartland Inventory and Monitoring Network monitor deer at Wilson's Creek National Battlefield to better understand how their populations may be changing over time. This information helps the park evaluate restoration of cultural landscapes, an important management activity at the park. Monitoring data also help park managers assess safety risks to people from disease and deer-vehicle collisons.

We began monitoring deer on the park in 2005 to determine yearly changes and long-term trends in their populations and to map their locations. Each year in winter, we use bright spotlights at night to count deer along the main tour road that makes a 7.9-km loop through the park. We conduct these surveys during a four-week period between January and mid-March.

NPS

Monitoring Highlights

(2005–2022)

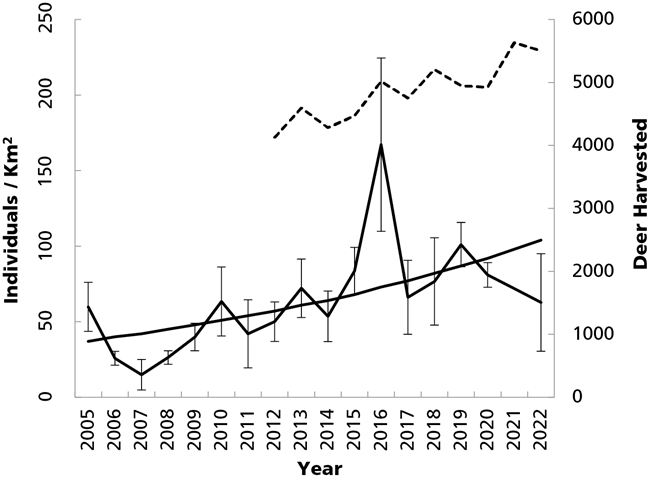

Over 18 years of monitoring at Wilson's Creek National Battlefield, we observed great variability in deer populations from year to year. We also recorded a rapid decline in deer and a recovery of the population. The deer population ranged from a low of about 15 individuals/km2 in 2007 after a two-year hemorrhagic disease outbreak to about 167 individuals/km2 in 2016. This recovery shows that deer populations have high reproductive potential.

Oak trees are central to the restoration of the oak-savannah landscape that was present at the time of the Civil War battle at Wilson's Creek. Deer like to browse on young tree seedlings, so success of the oak-savannah restoration projects relies on deer population control. Since hunting is not allowed in the park, disease is the primary natural factor that controls deer populations. The region-wide hemorrhagic disease outbreak that affected deer on the park started in the fall of 2005, six months after we began monitoring park deer. This disease can kill off 50% of the deer population each year and can persist for several years. Waiting for disease to control deer is harmful to deer, as well as people and other animals. We monitor deer so park staff can manage their populations to protect deer and park ecosystems.

NPS

NPS

Did You Know?

To survey for deer, we use very bright spotlights. While one person drives a vehicle very slowly along the deer survey route, two observers shine these spotlights to the left and right of the vehicle looking for deer. When we see a deer, we stop and measure the distance from the vehicle to the deer using a piece of equipment called a rangefinder. If there is a group of deer, we measure the distance to a single deer in the middle of the group. The direction and angle of the deer from the vehicle are also recorded to map deer on the park. To know how much area we have surveyed, we measure the visible distance from the vehicle every tenth of a mile along the survey route. The number of deer and the amount of visible area allow us to determine deer density (number of individuals per square kilometer) on the park.

For More Information

Read the full report.Check back later for updates. We will update this page each year as we gather information.

Web article created by the Heartland Inventory and Monitoring Network.