Part of a series of articles titled Whitebark Pine Monitoring in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

Article

Whitebark Pine Recruitment in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem – Data Summary of Monitoring in 2023

NPS/Shanahan

This is the fourth article in the article series, Whitebark Pine Monitoring in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

Articles 2 to 4 of this article series summarize data from Panel 4 transects surveyed between June and September 2023. This is the fourth revisit to these 44 transects for full survey data collection (see Figure 3 in Article 5—Methods—for the panel sampling revisit schedule).

This article presents results for the fourth objective of the Interagency Whitebark Pine Monitoring Protocol for the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

Objective 4 – Document the recruitment of whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis) into the reproducing population and assess the multiple factors that influence overall recruitment success over time.

Overview of Methods

(For detailed methods, see Article 5 and the monitoring protocol.)

While whitebark pine tree mortality occurs in all 176 sample transects in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, nearly every transect shows recruitment of new trees into the population. There are three indices of whitebark pine recruitment derived from the 10 meter wide by 50 meter long (10 × 50 m) transect surveys:

- the number of trees less than or equal to 1.4 meters (≤1.4 m) tall; labeled "understory" here

- the number of trees that grow to more than 1.4 meters (>1.4 m) tall

- the number of live tagged trees, regardless of height, that show signs of reproductive activity

Tracking cone-producing trees through time provides an indication of current and potential future tree recruitment.

Additional information about factors affecting recruitment, such as the abundance and composition of non-whitebark pine understory (<1.4 m tall) tree species, as well as ground cover, is collected in three circular, 1/300 acre (2.08 m radii) subplots along the midline of the rectangular transect (Figure 5 in Article 5—Methods). Note that 2 five-needle pine species occur in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem: whitebark pine and limber pine (Pinus flexilis). Because the two are difficult to distinguish as seedlings, some measurements are for “five-needle pine species” in general.

Note that data summaries from transects surveyed in any given year do not reflect the entire sample of transects; therefore, they do not represent the overall Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem population of whitebark pine and should not be used to draw wide-reaching conclusions about status or trends.

NPS/Erin Shanahan

Results for Objective 4—Recruitment

10 x 50 m Belt Transects

Regeneration and Growth

We counted 2,575 understory five-needle pines (≤1.4 m tall) on 43 Panel 4 transects. One transect had residual snow covering a portion of the ground; therefore, the understory survey was not conducted. This equates to an average density of approximately 60 small trees per transect. Thirty-one (1%) of these small trees were infected with blister rust.

In 2023, we tagged 89 new trees (>1.4 m tall) over 23 Panel 4 transects. Five (6%) of the newly tagged trees had evidence of blister rust infection.

Cone Production

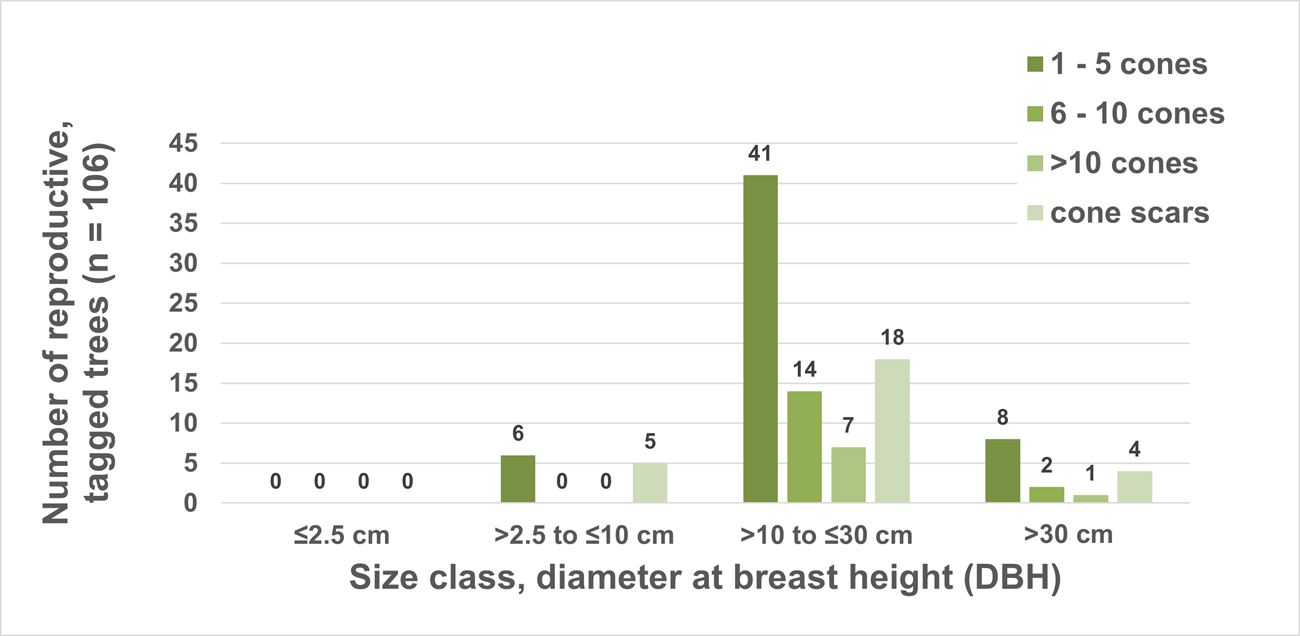

Evidence of reproduction (current year cones or previous year cone scars) was recorded for 106 tagged trees in 2023 on Panel 4 transects (Figure 1). For reproducing trees, cones are counted and categorized into five bins: 0 = no cones, 1 = 1–5 cones visible, 2 = 6–10 cones visible, 3 = >10 cones visible, and S = cone scars but no current year cones visible. Cones were predominantly observed on trees >10 cm DBH (95 trees). The most commonly observed cone class in 2023 was cone class 1, with 55 trees (52%) falling into this category (Figure 1). Whitebark pine tend to have large cone crops one year followed by a few years of low cone production. In 2023, cone scars were observed on 27 (25%) of the reproductive trees. (The presence of cone scars is an indication that a tree is capable of producing cones.)

Blister rust infection can significantly reduce or impede an infected tree’s ability to produce cones by blocking nutrient transportation to and from the canopy of the tree where cones are found. On Panel 4, 48 (45%) of the reproductively active trees had evidence of current blister rust infection. This is further broken down into 29 trees (60%) with infection occurring in the canopy and 19 trees (40%) with bole infection.

NPS

NPS/Shanahan

Recruitment Subplots

In 2023, 132 recruitment subplots (1/300 acre, three per transect) were completed on Panel 4 transects. In these 2.08 m radii subplots, counts of five-needle pines were recorded in four height categories (>0–15 cm, 15.1–61 cm, 61.1–140 cm, >140 cm; note that trees in the >140 cm category typically have tags already if they are within the 10 × 50 m transect boundary). All other tree species (lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta), fir (Abies lasiocarpa, Pseudotsuga menziesii), spruce (Picea engelmannii), and sometimes aspen (Populus tremuloides)) are recorded in two height categories (15–140 cm, >140 cm). Each five-needle pine tree was examined for signs of blister rust. In addition, ground cover, vegetation cover, dominant and codominant vegetation species were recorded.

These data are under review and will be included in future data summary reports.

Learn More

This web article will be updated regularly with new results, but the 2023 results presented here are summarized in a resource brief for 2023. For more results from past years please visit the Greater Yellowstone Network website.

Last updated: August 21, 2024