Last updated: March 1, 2022

Article

Walk This Way

"My Mama always said you can tell a lot about a person by their shoes. Where they're going, where they've been."—Forrest Gump

Do you know your Chukkas from your pumps and your Oxfords from Wellingtons? As anyone who has worked on their feet all day can tell you, comfort and durability are important, especially if you work outdoors—like, say, in a national park.

Seen as purely functional at one extreme and dismissed as fashion at the other, shoes in a work setting can provide insights into women’s jobs and how their career opportunities change over time.

Starting Off on The Right Foot

Early uniformed women rangers wore riding boots or shoes with puttees (wrap-around shin guards) in keeping with the uniform regulations in the 1920s that applied to both men and women. More importantly, the footwear was appropriate for the duties of the job and the locations in which the uniformed women lived and worked.

Trousers, accompanied by black or brown shoes, supplemented riding breeches for some positions beginning in 1928. Although a few women still wore boots in the early 1930s, there are no known photos of any wearing the uniform trouser and shoes option. Virginia Sutton wore pants at Mesa Verde National Park, but we haven’t found any photos to date to confirm if they were breeches or trousers. As women increasingly wore skirts in the 1930s, their shoes became much less uniform.

Feeling the Pinch

As women were hired as guides and museum aids rather than as rangers and naturalists in the 1930s, they began wearing skirts instead of breeches. Different jobs provided opportunities to be both fashionable and frugal.

Rising hemlines following World War I resulted in boots falling out of fashion in America in the 1920s. As mass production increased affordability for the middle class, shoemakers became shoe designers. Styles, materials, and color options for women in particular increased dramatically.

Photographs from the 1930s and 1940s show NPS women wearing loafers, one-straps (i.e., Mary Janes), and Oxfords with varying styles of heels. Although some were a heavy-duty serviceable type, most shoes seem best suited to office jobs or walking on flat, even surfaces (again, hardly a coincidence). Although personal style no doubt played a role in what shoes a woman wore with her uniform, wearing what she had and not spending money to buy a new pair of shoes just for work was likely more important—especially if the job was temporary or seasonal.

The variety in styles and colors in women’s shoes was stomped out (see what we did there?) when dark brown Oxford type shoes became the official women’s uniform shoe in the 1940s. Of course, that description still left a lot of room for variation, but it was the NPS’s first official foray into designated footwear for women in uniformed positions and an attempt at a more standard look—one that wasn’t always successful!

If the Shoe Fits

In 1960, the NPS continued to exclude women from park ranger jobs or jobs where they would be called to “fight fires, take part in rescue operations, or do other strenuous or hazardous work.” Appropriate work for women included presenting lecture programs, guided tours, and children’s programs; performing museum and library work; and conducting research. The shoes specified for the women’s uniform are a direct reflection of those kinds of jobs.

The 1961 uniform standard required plain, dark-brown pumps made of leather or reptile skin and with closed toes and heels. Heels were 1.5 to 2 inches high, and women were encouraged to show “good judgment in the selection of proper and comfortable footwear.” In a nod to some women’s roles as guides, brown, leather, low-heeled walking shoes could be worn on trails and nature walks. Women had more options for bad weather, including galoshes and black or brown pull-on boots.

More options arrived in 1962 when any women’s shoes could be worn, provided they had with either low Cuban or French heels and closed toe and heel designs. The specified color was cordovan (a rich dark brown with burgundy tones). Bows, ribbons, and brilliants (a fancy shoe term for things like rhinestones) were not permitted (definitely not the “ranger look”). Boot options included black zippered galoshes or black rubberized calf-length pull-on boots.

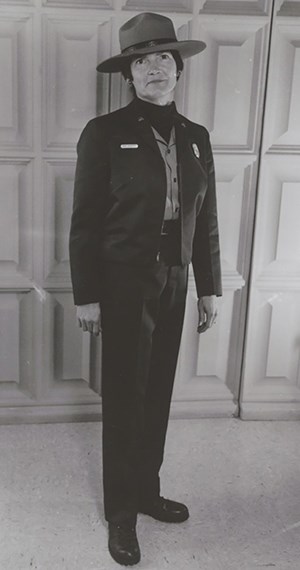

A dramatic shift came with the tan women’s 1970 uniform (in more ways than one!). As far as footwear was concerned, dark brown was out, and beige, tan, or light brown were in. These lighter colors were a departure from the color the men wore, but the idea was to match the same color family as the uniform—which in itself was a huge departure from the traditional “green and gray” uniform.

For the dress uniform, shoes were to be “simple in styling and have a comfortable heel.” Smooth or lightly grained leather was appropriate, but suede or reptile leather was no longer acceptable. Boots were optional for some classes of women’s uniforms. Winter boots could have fur lining. Work boots were to “coordinate as nearly as possible.”

Collection photo)

One Giant Leap

In 1974, the women’s uniform changed again (many would argue not for the better, but that’s not really about the shoes). Dresses and pantsuits required brown pumps, except in cold weather when dark brown boots were acceptable. A big step toward equality also occurred in 1974 when the women’s traditional uniform was approved for those whose primary duty involved contact with park visitors. Resembling the men’s “green and gray” uniform, it included more practical shoe options for both indoor and outdoor work. Before long, women had official options such as walking shoes, chukkas, and Wellington-style boots.

Not coincidentally, at that time women increasingly moved from largely office jobs to more diverse positions in interpretation, resource management, law enforcement, and maintenance. As they moved into these male-dominated fields, the footwear reflected their jobs. Over time, more career choices became available to women—and who wouldn’t want to be in those shoes?

Explore More!

To learn more about Women and the NPS Uniform, visit Dressing the Part: A Portfolio of Women's History in the NPS.

This research was made possible in part by a grant from the National Park Foundation.