Last updated: January 11, 2024

Article

Christmas at Valley Forge

NPS Image

article by Jennifer Bolton, Park Ranger at Valley Forge National Historical Park

"The Enemy’s main body, remain as yet, in status quo, I wish your Excellency a merry Christmas & all the Compliments of the Season.” ~ Major John Clark Jr. to General George Washington. December 25, 1777.1

On December 19, Washington and the Continental Army arrived at Valley Forge. There, they established a winter encampment twenty miles northwest of British-occupied Philadelphia. Many wonder how the army celebrated Christmas that year. It depended on several factors, partly because observances varied between different religious demographics. Traditions also changed drastically between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries. By taking a broad perspective, a clearer understanding of revolutionary-era celebrations emerges.

NPS Image

Many Different Faiths

The Continental Army comprised a diverse demographic of soldiers and civilian followers. Christian adherents included Lutherans, Episcopalians, Congregationalists, Methodists, and Baptists (among others). Folklorist Don Yoder writes, "If one belonged to the Episcopalians or Lutherans or some other pro-Christmas denomination, one celebrated Christmas; if one was a Quaker or a Mennonite or a Presbyterian, one did one's best, like the Puritans, to ignore it."2 So, many Christians would not have observed the holiday at Valley Forge, especially New Englanders.

Some individuals (such as Dr. Philip Moses Russell) practiced Judaism, and a few of the over seven hundred Black soldiers encamped at Valley Forge probably practiced Islam or different African religious traditions, unrelated to Christianity. Members of the Mashantucket Pequot had enlisted on an indiviual basis, as did other Native American Indians. While many of them had converted to Christianity, they might have practiced a syncretized form of the faith or not have celebrated Christmas in a form we would recognize. In short, holiday observances would have appeared as diverse as the citizens and soldiery themselves.

NPS Image

A Puritan Influence

The Christmas as we know it today differed from historical customs. During the English Civil War between 1642 and 1651, the Puritans gained political power. Hailing from the Puritan tradition, New Englanders held more conservative religious beliefs than Anglicans. The former saw Christmas as an increasingly debauched holiday of drinking and merriment. Puritans also associated Christmas celebrations with Catholicism, which they abhorred. So, they passed legislation banning Christmas celebrations in England.3

Many New Englanders shared the Puritans’ beliefs, so they also discouraged and later banned Christmas celebrations. The holiday festivities remained illegal in Massachusetts until 1856. By the mid-nineteenth century, the Puritan influence waned, and traditions (that we associate with the holiday today) developed anew.

In 1800, Queen Charlotte introduced the first Christmas tree in England. Christmas trees gained more widespread popularity in the mid-century, when periodicals described the royal trees Prince Albert had imported from his native Coburg.4 Concurrently, people started exchanging cards, and they renewed an older tradition of singing carols—a practice originating in the medieval era. With the 1843 publication of A Christmas Carol, Charles Dickens reinforced many of these practices, but he also introduced a spirit of generosity during the season.5 So, many traditions that we recognize today developed in the nineteenth century.

But how did people celebrate Christmas during the revolutionary era?

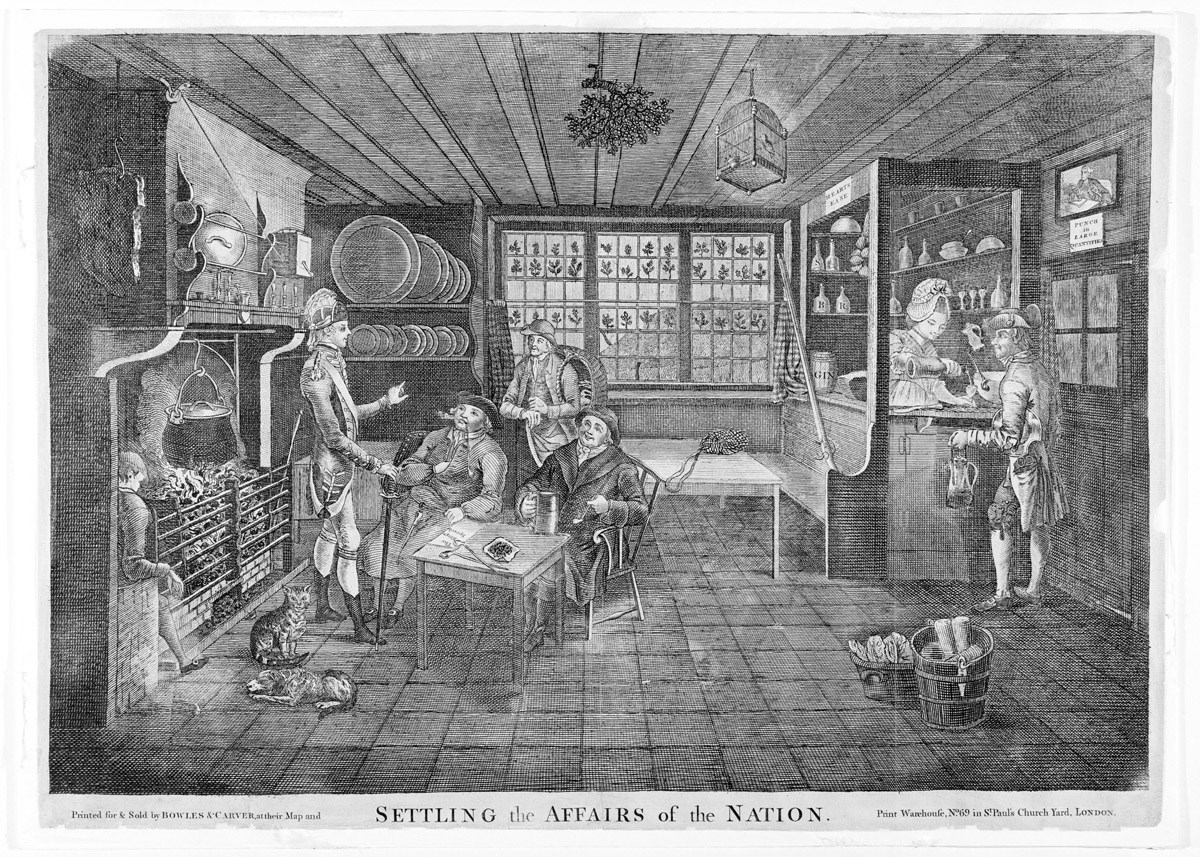

Courtesy Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library - Settling the Affairs of the Nation - Bowles and Carver - London, England; 1794-1800 - Ink on laid paper - Museum purchase 1973.561

Christmas Among Virginian Anglicans

In the eighteenth century, Christmas observances varied among Virginia’s Anglicans (such as George Washington). A family might have Christmas dinner, or they might not. Some attended religious services, while others stayed home. And their holiday observance could vary from one year to the next. Virginian Anglicans considered Twelfth Night or Epiphany (January 5 or 6) more significant than Christmas, and they often enjoyed the Twelve Days of Christmas between the two dates.

An itinerant teacher, Phillip Vickers Fithian wrote that Virginians “will dance or die.”6 They often danced late into the night, and parties could get bawdy. Some also celebrated the morning by firing Christmas guns—something that Virginia’s Baptists or Methodists frowned upon. Virginians often married during one of the Twelve Days of Christmas, especially since it took place during a low point in the agricultural year. Thomas Jefferson married on New Year’s Day and George Washington married on Epiphany. Usually, marriages occurred in the home, rather than at church—which differed from English practices.7

Christmas Among Enslaved Africans

For many enslaved people, the Christmas season offered one of the few times they could rest and enjoy themselves.8 Enslaved laborers experienced different levels of down time, depending on work in either the task or gang systems of labor. And of course, enslaved chefs, manservants, and other household workers likely remained busy during the holiday festivities. Also, enslavers sometimes leased out the people they held in bondage, with leases potentially beginning in the new year. Enslaved families experienced separation, but they might have someone return home as well—a potentially bittersweet time of year. Nonetheless, most slaveholders granted their enslaved workers an opportunity to break from labor.

NPS Photo

Christmas in the Winter of 1777

Lancaster resident Christopher Marshall corresponded frequently with Continental Army officers at Valley Forge. As a Quaker, he had a negative view overall of Christmas. On December 25, 1777, however, he wrote that “no company dined with us to-day, except Dr. Phyle, one of our standing family. We had a good roast turkey, plain pudding, and minced pies.”9

Ironically, the Quaker Marshall had a more festive Christmas than many in the Continental Army, since the poor supply situation meant that they had more pressing concerns. Congress had established December 18 as a day of Thanksgiving. It occurred a day prior to the army’s march into Valley Forge. Yet Surgeon’s Mate Jonathan Todd Jr. wrote to his father about their meager celebration during the holiday season, “I never saw A Christmass when I had no other Covering than Tow Cloth before – On the Day appointed for the Continental Thanksgiving We drew ½ Gill of Rice pr man which with Beef & Flower were the dainties of our Feast.”

Other primary source documents offer clues on Christmas observances during the Valley Forge encampment, such as they existed. Many soldiers subsisted on firecake, which consisted of flour and water cooked over a fire. With little nutritional value, it often made them sick. On December 22, Surgeon Albigence Waldo wrote that Providence had “sent us a little Mutton, with which we immediately had some Broth made, & a fine Stomach for same.” He went on to criticize the ungratefulness of those in better circumstances: “Ye who Eat Pumpkin Pie and Roast Turkies, and yet Curse fortune for using you ill, Curse her no more, least she reduce your Allowance of her favours to a bit of Fire Cake, & a draught of Cold Water, & in Cold Weather too.”10 Others fared worse, doing entirely without. Lieutenant Samuel Armstrong wrote in his diary: “Christmas Day. We was without provisions therefore I was sent out to procure some […] As soon as I returned, I was call’d out to go upon Scout & did not return ‘till about 10 OC. in the Evening. This was my Christmas frolick.”11

So, as many of us today gather ‘round to celebrate the season with loved ones over festive meals, take a moment to consider those less fortunate, to include the soldiers and civilians who supported the Continental Army during the Christmas of 1777, at Valley Forge.

NPS Photo

Endnotes

1. “To George Washington from Major John Clark Jr., 25 December 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-12-02-0650. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 12, 26 October 1777 – 25 December 1777, ed. Frank E. Grizzard, Jr. and David R. Hoth. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2002, pp. 704–705.]

2. Don Yoder, Christmas in Pennsylvania: A Folk-Cultural Study, 50th Anniversary Edition (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2009), 2.

3. “Did Oliver Cromwell Ban Christmas?,” The Cromwell Museum, accessed December 5, 2023, https://www.cromwellmuseum.org/cromwell/did-oliver-cromwell-ban-christmas.

4. “A Short History of Christmas Greenery,” English Heritage, accessed December 5, 2023, https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/learn/histories/christmas-greenery-history/.

5. Penne L. Restad, Christmas in America: A History (United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, USA, 1995), 45.

6. Philip Vickers Fithian, Philip Vickers Fithian: Journal and Letters, 1767-1774. (Carlisle, MA: Applewood Books, 2007), 235.

7. For more information on Virginian Christmas observances, read Harold B. Gill, Jr., “Christmas in Colonial Virginia,” The Colonial Williamsburg Official History Site, https://www.slaveryandremembrance.org/almanack/life/christmas/hist_inva.cfm.

8. General Assembly. “‘An Act for making more effectual provision against Invasions and Insurrections.’ (February 1727)” Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Humanities, updated September 11, 2023, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/an-act-for-making-more-effectual-provision-against-invasions-and-insurrections-february-1727/.

9. Don Yoder, Christmas in Pennsylvania, 2-3.

10. Albigence Waldo, Valley Forge, 1777-1778. Diary of Surgeon Albigence Waldo, of the Connecticut Line (Philadelphia: The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 1897), 311.

11. Joseph Lee Boyle and Samuel Armstrong, From Saratoga to Valley Forge: The Diary of Lt. Samuel Armstrong, The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Jul., 1997, Vol. 121, No. 3 (Jul., 1997), 259-260. Courtesy of JSTOR.